Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

Volunteers are at the heart of any hospice program. In fact, the Medicare Conditions of Participation for hospice care require that five percent of all care be given by volunteers. Why would such a regulation exist? There are many reasons.

Hospice programs are designed to treat the entire family, from the time of admission through a year after the patient’s death. No one person can fulfill all of the needs of every family member, but the presence of an active volunteer program makes it much more likely that patients and families can have their pressing needs met. Volunteers are an extension of the staff, and make it possible for a hospice to do more for everyone.

Volunteers bring talents that might not be possessed by anyone on the paid staff. Whether it be hairdressing, reiki, massage therapy, gardening, or knitting, those who come to volunteer have a variety of competencies, many of which may be apart from any professional skills. It’s not uncommon to find a retired CEO that can fix things, a teacher who does massage therapy, or a former librarian who can get office work done.

Volunteers don’t have to do the everyday tasks, so they can go above and beyond for patients and visitors. One of the most popular assignments is something called a “loving whisperer”—a person who sits by a dying patient, who has no relative present, holding a hand or giving comfort in other ways. People who like to drive, and who might bring a family member who doesn’t have a car to visit, or pick up a prescription and deliver it to a homebound patient, are like gold to a stretched paid staff.

Therapy pet owners are mobbed as soon as they come off the elevator. Everyone, including the professionals working at the hospice, are happy to pet a dog with a wagging tail. The cheer they bring is hard to duplicate with humans!

Time is often a precious gift in and of itself. Volunteers may roll beds outside on a sunny day, or even just sit and listen to stories, confessions, memories, or fears. They learn to just “be”, in a rushed world where everyone has a job to do. At the end of life, the days may be short, but the minutes and hours can be long. How much better it can be to talk to a willing listener, than to watch daytime TV! These helpers are often around at times with fewer visitors, and many have the patience to simply sit in silence, or to be a cheerful face when a patient wakes up from a nap.

Many volunteers also willingly do daily tasks that free others up. One such duty is checking visitors in at the front desk. Those cheerful souls calm and comfort anxious guests, making a huge difference just with a few kind remarks. One such volunteer noted that men, in particular, are often uncomfortable in such medical surroundings, and are gratified to be greeted and recognized as grieving relatives. Sometimes they find it easier to unburden to a stranger, and volunteers are practiced at letting them do just that.

The same holds true at the bedside, where deep feelings may be expressed. One volunteer spoke of listening to a woman over the course of her stay, vocalizing gratitude for her husband coming faithfully each day for lunch. After she passed away, the volunteer was able to communicate that gratitude to the husband, who had never heard it directly from his wife. Stories like that are not unusual, and mean so much to those left behind.

What do the volunteers get in return? Most say immediately that they receive more than they give.

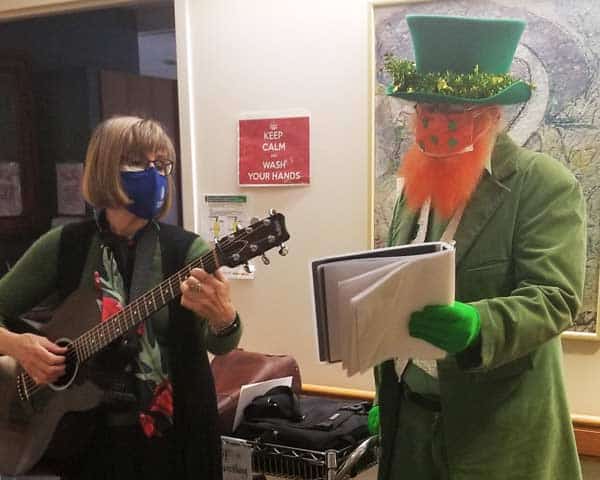

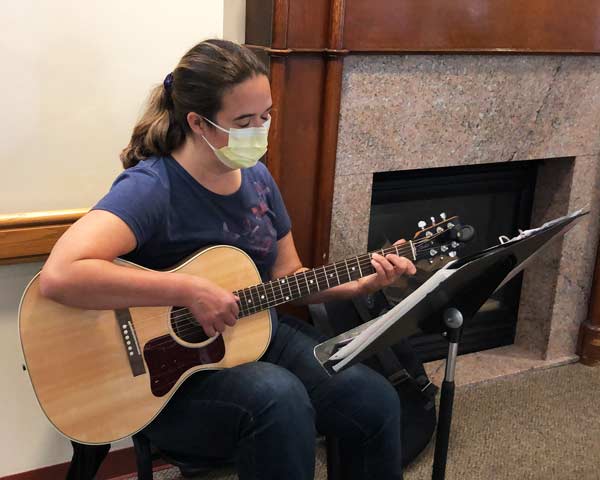

Many musicians have a day job doing something completely different, so they enjoy getting the chance to play for an audience. Families can connect within their own group, or even with other families, through music. Patients may be soothed, or even energized, as is the case with some suffering from dementia, by favorite songs. One man who hadn’t spoken in days, but who had been a competitive ballroom dancer, opened his eyes after his wife requested a specific number from those days, and asked “shall we dance?”. Moments like that keep volunteers coming back over and over.

Many are laypeople, but with an interest in spirituality of all kinds, and a desire to offer that to those requesting it. Even those without formal religious views can find solace in discussing some of life’s biggest questions with these dedicated helpers. In the vein of the old saying that the best way to learn something is to teach it, they feel enriched by experiencing the faith, and doubts, of others.

Many students, whether training for medical careers, doing community service, or just giving some extra time, find that they are amazed by everything that they learn while volunteering. Some say it was the most transformative part of their education. Others are moved to search for a career in hospice or a related field. Students who do technological projects may not be taking care of patients, but they are certainly exposed to the philosophy of palliative and hospice care. For those who are in medical, nursing, or paraprofessional schools, it may be very different than what they are taught in settings where curative care is the guiding principle.

Not only medical clearance, but fingerprinting (if working with patients), interviewing, and training are all mandated. Most hospices also ask that applicants wait a year after a personal loss to become a volunteer. Rather than considering that list to be a high hurdle, it should be seen as a compliment, to show that volunteers are just as important as employees, and should be vetted that way.

It’s easy now to see why volunteers are so critical to a hospice. Indeed, their passion for the mission is inspirational not only to patients and families, but to the paid staff as well. The staff not only acquire extra hands and minds to aid in their work, but are buoyed by the caring and support of those who show up faithfully to help, week after week. Some come daily, some weekly, and some seasonally, but all bring the reminder of the meaning of hospice care.

They all are clear on one thing: Hospice work for them is anything but depressing. They speak of it as “joyous”, gratifying, and rewarding. All value the human connections they find in those settings. In doing their important work, they find meaning. And they are grateful—for health, for life, and for every day. What more could a volunteer, or indeed anyone, ask?

The Hospice Plan of Care (POC) maps out the needs and services supplied to hospice patients and their caregivers.

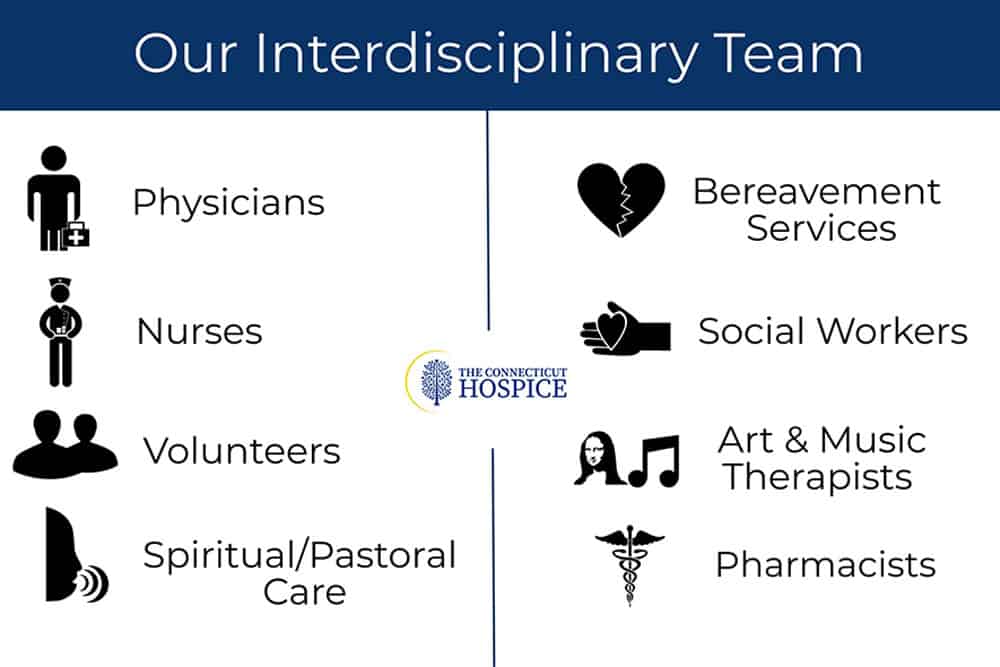

If one wanted to probe the essence of the hospice philosophy, it would probably come down to the hospice plan of care, developed for each patient on admission, and revisited every two weeks after that, by the interdisciplinary team managing that individual patient. This plan is mandated under Medicare for hospice reimbursement and has very specific requirements that all hospices must follow. It isn’t just that various disciplines are included in the plan, but that all the practitioners convene to contribute to it. The Connecticut Hospice is very familiar with all these components, since our Founder, Florence Wald, wrote extensively about the various aspects needed for proper patient treatment, as she worked to bring the first hospice care to America almost fifty years ago.

At the heart of what Florence Wald believed was the notion that patients have rights, and should be treated as partners in the care that they receive. She thought, and it was novel at that time, that they should be told their diagnoses and prognoses, and that the whole family should be involved in planning and care of the illness. It seems hard to imagine now, but cancer patients were often not told what their disease was, nor were they advised if it was terminal. This was seen as a kindness, but Ms. Wald felt that it impeded a patient’s ability to achieve closure, and to plan for his or her last days, weeks, or months of life. Today this appears obvious, but, at the time, it led to the idea that there should be an informed discussion about options, treatment, and a patient’s wishes.

This Hospice Plan of Care goes far beyond the concept of advanced directives that many people are familiar with from medical practice currently. It is a plan for comprehensive care that includes preferences about pain medication, sedition, home vs. hospital vs. hospice as a location of care, treatment choices, comfort measures desired, and family involvement. It also includes the more expected areas of funeral arrangements and religious practices, as well as financial considerations.

To many patients and families, the end of life can come as a surprise, no matter how often they may have spoken of the possibility. Too often, they can feel as though they have boarded a train that is proceeding quickly, and without their full informed consent in some instances, toward a destination, they may not feel that they have accepted. There can also be a sense that everything is preordained—that the medical profession will be deciding the next steps, based on superior knowledge. This usually leads to further treatment, either because paths forward presented as possibilities are not understood to be optional, curative, or even recommended, or because someone in the group is choosing extended life as the goal for action, no matter the chances or consequences. Without deliberative planning, this runaway train can end up in a place no one consciously intended to go.

How does a hospice plan of care prevent this runaway train of futile, expensive, and often painful curative attempts? First of all, the care plan is patient and family-centered. The aim is to make sure that the patient’s goals of care and treatment wishes are honored. Palliative care is very different from curative treatment, and both are explained. Comfort Measures Only (CMO) is a totally valid decision to make, and can, not infrequently, even lead to a longer life span. Treatment can be enervating, and frequent trips to the ER or lengthy hospital stays can weaken patients further, and lead to other issues.

Pain is another important topic. Not everyone has the same pain tolerance. Even if they did, some will choose to be more sedated than others, depending upon their own wishes for family visits, final projects, or other reasons. This is crucial to decide with the patient, if possible, since family members, or even the medical team, can be upset by signs of suffering, and want to have them alleviated.

Independence and residence are critical to discuss. For some, living at home is vitally important. Others may be afraid to be alone, or feel more comfortable with attendants around, either in the home, or in a skilled nursing facility. Some wish to undergo rehabilitation, to acquire the strength or ability to perform certain skills. Different options can also be right at different points.

When the end of life approaches, there can again be different preferences. Inpatient hospice care is often chosen by those who don’t wish to burden their relatives with personal care, or perhaps feel that their surviving family will be unhappy to have had them die at home. Some caretaker relatives may be increasingly unable to provide the level of support needed as the disease progresses. In other situations, the patient’s strongest wish may be to die at home. When this is true, all parties need to examine all the requirements necessary to achieve that result. For those who have spent a great deal of time in a particular hospital unit, they may wish to remain in a bed there.

Treating unrelated conditions is another consideration. Sometimes, antibiotics are used, even in CMO cases, to make the patient more comfortable. Others may wish to continue medications they have previously been taking. Many find letting go of all restrictions, dietary or otherwise, is a welcome relief. For them, the team dietician may be less important, but some families struggle to keep patient appetites up, and find that consultation valuable.

Social work, arts therapy, and spiritual care members of the Interdisciplinary Team are involved as well, not only for the typical end-of-life financial or funeral planning, but for help with bereavement and grief. The patient will rest more easily if resources are provided to work on those issues. The patient him- or herself may have spiritual questions or concerns. He or she may simply want to talk to a neutral listener, without fear of hurting feelings or causing pain. Working with an arts therapist, either in home care or in the inpatient unit, can be a way of creating new memories, or accessing old ones. Children especially tend to gravitate toward expressing their feelings through art and music. Assessments in these areas are done at the start of care, and reviewed, with action plans updated, on a regular basis.

How does all of this differ from what a patient and/or the family might accomplish alone? It isn’t always different. Some families are familiar with final illnesses, or extended personal care. Some have talked about what end-of-life wishes are, and all agree on one plan from the outset. If an illness has been lengthy, often especially in cases of dementia, decisions have already been made at various points. For others, however, this plan of care is a helpful introduction to all of the issues involved. For them, the caregiving team is very important in allowing them to accept, cope with, and come to terms with the process. Because there are many disciplines represented on the team, it can happen that different parts of the family relate to different styles or outlooks, and everyone can find relief in some regard.

Dr. Joseph Sacco, the Chief Medical Officer at The Connecticut Hospice, is certified in palliative care medicine, which he has been practicing for many years. He finds patient choice to be a true priority in good hospice care. As he explains, “What is left is choice — the right of patients and families to decide what their doctor should do, based on facts delivered clearly and with compassion.” That quote captures so well the philosophy of hospice: that it is the patient and family who are at the center of the constellation and driving the plan of care, and not the medical team. It is important for all parties to recognize that, even when it seems that there are no choices left, there are choices.

The decision as to how the end of life should unfold is a gift that all hospices can provide to their patients and families, and one that should never be taken for granted. It goes all the way back to the beginnings of hospice care, first in London, and then in Connecticut. The aim is to provide comfort and compassion, and allow all the dignity of fulfilling whatever wishes they can, to the best of their—and our—abilities.

A Comprehensive Breakdown of the Clinical Signs for When Hospice Care is Appropriate

Hospice care is a holistic approach to treatment that focuses on the patient and family which addresses the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual needs of the patient and family.

At Connecticut Hospice, we understand that it is a highly personal decision to begin receiving hospice care and we value the choices and goals of each patient and family. We are here to help you make the decision of when it's time for hospice care.

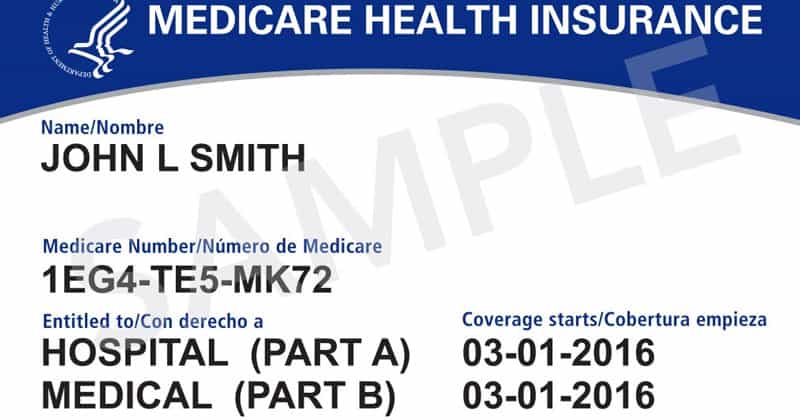

Medicare Hospice Benefit Eligibility

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2021

The patient is unable to be weighed on scales due to bed-bound status. MAC is 18cm to the right upper arm. During the interview with the daughter, who has been caring for the patient over the past year, she said that her mother has lost weight in the past 3 months but unable to state how much. The daughter states that she has been wearing clothing in a size 16 women’s but now she had to get mother new clothing gradually over the past few months due to her clothing “falling off of her”. The patient is now able to wear size 10 women's clothing.

The patient has been eating 4-6 child-size meals per day but has only eaten about 25% of each meal. This consists of 2 slices of bacon, 3 bits of grits for breakfast. She had a 1/3 of an Ensure supplement, then for lunch, she had a few bites of homemade soup and a popsicle.

The patient requires assistance of one for bathing at the sink, dressing his lower body and now uses a walker for all ambulation inside and outside of his room. The patient was completely independent with all ADL’s and driving and working every day until 3 months ago when he was diagnosed.

The Nurses Aide describes the patient is sleeping 8-10 hours at night and then takes a 3-4 hour nap during the day. When the patient is up in the chair for more than an hour, she is frequently dosing off. This is a change from just 2 months ago when the patient was not even sleeping during the night and was having agitation in the evening and sleeping a few hours during the day only

(HIV Disease, Stroke, and Coma require a lower score to qualify)

| % | Ambulation | Activity Level Evidence of Disease | Self Care | Intake | Level of Consciousness | Est. Median Survival in Days (a) | Est. Median Survival in Days (b) | Est. Median Survival in Days (c) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | Full | Normal No Disease | Full | Normal | Full | NA | NA | 108 |

| 90 | Full | Normal Some Disease | Full | Normal | Full | NA | NA | 108 |

| 80 | Full | Normal With Some Effort Some Disease | Full | Normal | Full | NA | NA | 108 |

| 70 | Reduced | Can't do Normal Job or Work Some Disease | Full | Normal or Reduced | Full | 145 | NA | 108 |

| 60 | Reduced | Can't do hobbies or housework Significant Disease | Occasional assistance needed | Normal or Reduced | Full or Confusion | 29 | 4 | 108 |

| 50 | Mainly sit/lie | Can't do any work Extensive Disease | Considerable assistance needed | Normal or Reduced | Full or Confusion | 30 | 11 | 41 |

| 40 | Mainly in bed | Can't do any work Extensive Disease | Mainly assistance needed | Normal or Reduced | Full or Drowsy or Confusion | 18 | 8 | 41 |

| 30 | Bed Bound | Can't do any work Extensive Disease | Total Care | Reduced | Full or Drowsy or Confusion | 8 | 5 | 41 |

| 20 | Bed Bound | Can't do any work Extensive Disease | Total Care | Minimal | Full or Drowsy or Confusion | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| 10 | Bed Bound | Can't do any work Extensive Disease | Total Care | Mouth Care Only | Drowsy or Coma | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| 0 | Death |

| 100 | Normal no complaints; no evidence of disease | |

| Able to carry on normal work; no special care needed | 90 | Able to carry on normal activity; minor signs or symptoms of disease |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | Normal activity with effort; some signs or symptoms of disease; | |

| 70 | Cares for self; unable to carry on normal activity or do active work. | |

| Unable to work; able to live at home and care for most personal needs; varying amount of sassistance needed. | 60 | Requires occasional assistance; but is abke to care for most personal needs. |

| 50 | Requires considerable assistance and frequent medical care. | |

| 40 | Disabled; requires special care an assistance. | |

| 30 | Severely disabled; hospital admission necessary; active supportive treatment necessary. | |

| Unable to care for self; requires equivalent of institutional or hospital care; disease may be progressing rapidly. | 20 | Very Sick; hospital admission necessary; active support treatment necessary. |

| 10 | Moribund; fatal processes progressing rapidly. | |

| 0 | Dead |

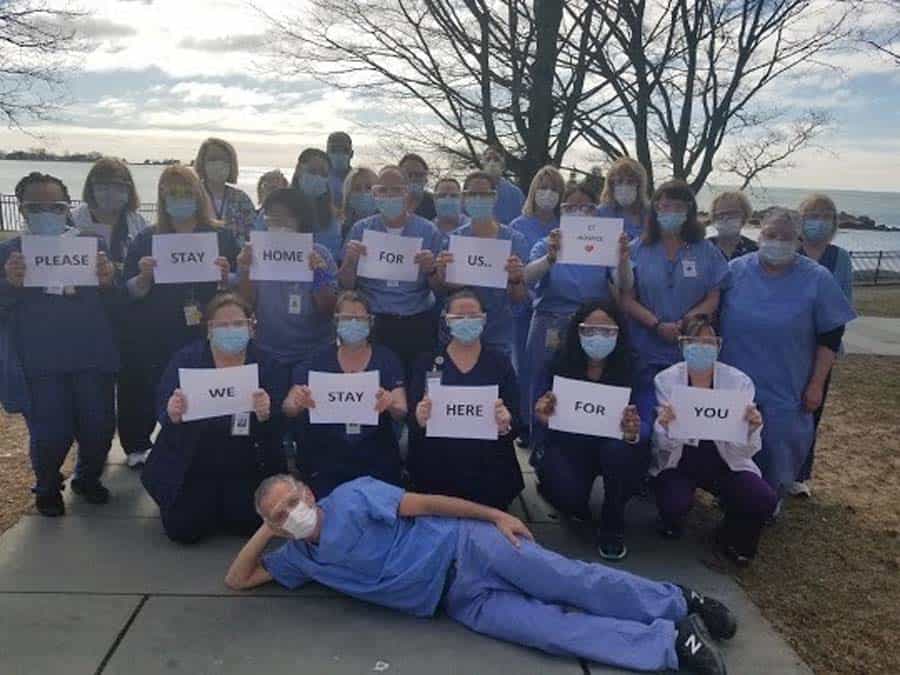

One of the comments we often get from people we meet in the community is that it must be “so depressing” to work in a hospice. They are always surprised that those of us who do work in one don’t find it to be that way. In taking an informal sample of employees at The Connecticut Hospice recently, there is quite a bit of uniformity on this topic.

It matters to all workers everywhere to find meaning in their work. Hospice work intrinsically falls into the category of meaningful employment. It isn’t just a job. It’s a calling, even for those who have non-clinical positions. They feel that what they do matters, and that they would find a for-profit, non-healthcare situation inherently different. A sense of mission is palpable in the air.

The work is all around us. Most employees who aren’t clinical work within one floor of the inpatient unit. They share elevators and stairs with visitors and families. They handle paperwork for patients currently housed in our facility. That proximity works in precisely the opposite way that the average bystander might expect.

Hospice employees leave every day with gratitude for interaction with loved ones, exposure to nature and the outside world, and the gift of time. They realize that our days are short, and health is uncertain. That makes them desire to live life to the fullest, and to savor small pleasures.

It also puts troubles and negativity into perspective. When having a tough day, a visit to the inpatient floor is a reminder of our good fortune, and brings feelings of gratitude. Especially during the pandemic, we can take solace, no matter what our problems, in being able to make someone else’s final days better and more rewarding. That also serves as a reality check on everything else in our lives.

Many of our employees have had relatives pass away in our hospice care. Seeing what we do first hand is a formative experience for them. It also enhances the sense of family that exists among the staff. We are there for the patients and families, and we are there for each other. We pull together in times of need, and work as a team, to help everyone we touch to experience this level of care.

Employees can better support their friends and relatives through loss, as they’ve learned to accept the pain, listen, and just be present for others. As one said, “End of life care shouldn’t be taken for granted”. They feel strongly about closure, and find the moments precious, even when the days are short.

Maybe surprisingly, we find a lot of joy in celebrating those moments, whether by pulling together a surprise party (or even a wedding!), bringing in a cherished pet, or wheeling a patient’s bed outdoors for some spring sunshine. The building is filled with music and art, as well as more laughter than one might think. Memories are made, or relived. Holidays are special, as they are often the last ones a patient might enjoy. Every day matters.

The saying that we get more out of hospice than we put in may be trite, but, for so many of us, that rings so true. Whether we spend our working hours billing, cooking, filing, or fundraising, we take meaning from our surroundings, and pride in what we do. What more could you ask from your work?

As a volunteer for Connecticut Hospice, you can choose the best role and time that works for you, from weekdays or weekends, to mornings or evenings.

Opportunities to make a difference as a volunteer continually arise.

Those who come to Connecticut Hospice join a community and have the opportunity to pursue a challenging and rewarding career in the healthcare field.

We offer opportunities for growth that include a range of clinical and administrative positions.

One special aspect of our gorgeous waterfront setting is the chance to be part of the circle of life. All year long we see nature in its many forms, from storms and wind in winter, to sun and flowers in bloom in summer. One season stands out, though, and that is spring—which is full of life in every way, especially with birds returning to visit, and to nest. Even among the bird population, one species stands out: Gulls are everywhere.

We pay a lot of attention to gulls. The variety we have at Connecticut Hospice are commonly called seagulls by most people, although technically they are usually herring gulls—named for one of the types of fish that they like to eat. They arrive in force at the end of winter, and they appear on every angle of our building, as well as along the water and on the grass. If you look at our building from afar, you can see them perched like little soldiers, guarding their territory. And they do consider it theirs!

Gulls mate for life, and they return to build nests on flat surfaces. That includes our roof and our balconies. Nesting birds are protected, so even our much-needed roof repair had to be done so as to avoid mating season. Once they build their nests, mostly out of grass and twigs, we can’t go anywhere near them. They are fiercely protective of their eggs, and the male and the female gulls take turns sitting on the nest. They will screech, fly at, or peck on the windows of people they find too intrusive.

Gulls lay around 3 eggs a year, and those that hatch spend about six weeks being fed with regurgitated food that both the male and the female bring back to the nest. At the end of that time, they are ready to fly.

When they aren’t being doting parents, they are often viewed as pests by those of us inured to their charms. They scavenge, to the point that they can swoop in and take a sandwich right out of someone’s hand. They also eat a lot of garbage, as well as fish, mice, and earthworms. Apparently, some groups of gulls can coordinate a stomping brigade, that can fool earthworms into coming aboveground, thinking that it’s raining.

Once they have reproduced, they seem less ubiquitous, although they remain a presence everywhere around our grounds. They share our back lawn with geese, and we all know about goose droppings, and how much we enjoy having those around. One of the neighbors who came to one of our vaccination clinics earlier in the year offered to bring her poodle by every day, to help chase the geese off the lawn. Good luck with that!

It seems everywhere on the Shoreline that large predatory birds have increased in number over the past few years. It’s common to see osprey (often carrying fish in their talons), hawks (ditto), and bald eagles can occasionally be spotted as well. Herons are abundant, although rarer for us to see from the building. Patients and their families not only go outside to view all the wildlife, but they bring binoculars to enjoy the viewing. We also have a very good telescope in the common room.

Watching the birds is a wonderful reminder of both joy and sorrow. Their lives can be harsh, and short, but they look so beautiful and free as they soar gracefully above the sparkling water. Gulls are even able to remain motionless in the air, by angling their bodies in a particular way to catch the wind correctly.

They remind us too, in their laser focus on finding and bringing back the next meal, that moments matter, and should be cherished and shared with loved ones, whether in a nest or by a bed.

We are including a few amazing photographs, taken by a new volunteer, for you to enjoy. We hope that you will find beauty in them, and in all of nature’s bounty. And may your spirits soar as these birds do.

Many of the founders of Connecticut Hospice left papers at Yale and in other places. Florence Wald, our founder, wrote notes and articles that teach us a great deal about what the attitudes and practices in medicine were that led to the need for changes in end-of-life care. Dennis Rezendes, the first paid Administer of Connecticut Hospice, also founded the first national hospice organization, which evolved into today’s National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO). They have kept his memoir, which adds richly to the material already stored around New Haven.

We knew that Florence Wald met Dame Cicely Saunders, the founder of Saint Christopher’s in London, the world’s first hospice, at a talk at Yale Medical School in the early 1970s. She stepped down as Dean of the Yale School of Nursing to spend time in England, learning about hospice care, with the goal of bringing it back to Connecticut.

When she did, she assembled a group of doctors, including Morris Wessel and Ira Goldenberg, nurses, nuns, and ministers, including Ed Dobihal. They formed the core of what became The Connecticut Hospice. When Dennis Rezendes came along, having spent ten years in the administration of New Haven Mayor Richard C. Lee (which also produced national figures in urban planning and other fields), he began the political process of forming an organization. By July of 1974, Connecticut Hospice was providing home care to patients from an office housed at Albertus Magnus College in New Haven. Meanwhile, Rezendes pursued building an inpatient facility for Connecticut Hospice in Branford.

The very first grants came from the Connecticut Medical Regional Planning Group and The New Haven Foundation, which became the Community Foundation for Greater New Haven that we know today. Rezendes worked with many of the State’s political leaders in order to secure the legislation and the funds to move forward. He was close to Governor Ella Grasso, who championed hospice care from the beginning. She helped obtain funds for building and even budget money for what became the J.D. Thompson Institute, which still is the parent corporation over Connecticut Hospice, and which brought hospice training to Connecticut and the country. Sadly, she died of cancer shortly after stepping down as Governor due to her illness, and without hospice care herself.

On the national level, there are wonderful stories of the various connections made and used to pass national legislation allowing Medicare to cover hospice care. The bill was signed in 1983 by President Ronald Reagan, but the groundwork began much earlier, and involved both Congressman Robert Giaimo of Connecticut’s Third Congressional District and many others, including Senators Ted Kennedy and Bob Dole. Connecticut Hospice was the first of the many hospices to be paid by the Center for Medicare Services, and today accounts for 87% of its budget. Originally, insurance companies were approached one by one, especially since Connecticut had so many headquartered here; today, the benefits are broader and more common.

There are wonderful stories about early deficits covered at the last minute by angels giving gifts (that hasn’t changed!), help is given by so many politicians (again, nothing new there!), and twists and turns along the way. One such gift became the seed money for the Charlie Mills Day Care Center, where toddlers shared common areas with Connecticut Hospice patients. Our current Board Chair’s daughter attended, and we have a clip of a young Tom Brokaw narrating the story of the daycare at our original location, on the NBC Evening News. While the Connecticut Hospice no longer houses a daycare facility, we allow the Town of Branford to use our beautiful waterfront pool for recreational swimming, bringing children and families into the building again. During the Holidays, patients and staff members bring children for an afternoon of arts and crafts and visit with Santa.

The groundbreaking for our first inpatient facility at 61 Bourbon Drive in Branford, had over 1200 people attending, and took place in November of 1977. It was made possible with a State grant, a Kresge Foundation gift, $1 million from the department of Health, Education, and Welfare, (now HHS), some individual fundraising, and a mortgage from the First New Haven National Bank, through the assistance of its President, Tom Hooker.

One of the many delightful side anecdotes involves New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre production of The Shadow Box, written by Michael Cristofer about hospice care at Connecticut Hospice. With the understanding that the 1970s was a very different time, Rezendes was worried because one of the main storylines involved a gay couple. He was afraid that it would bring negative press to Connecticut Hospice, and tried to get the theater’s Chair, Newt Schenck, to block the production. He writes about sitting nervously in the darkened theater on opening night, realizing that the audience loved the moving and important play. It went on to Broadway, where it won a Tony. It also won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, so it is truly fortunate that he was not able to stop the Long Wharf premiere!

Of course, Connecticut Hospice went on to move once again, to its current location, in another interesting chapter of our story. That involves the transition of the Double Beach Club, a local tennis and swim facility, into the Echlin Company’s world headquarters, and then into Connecticut Hospice beginning in 1999. Fred Mancheski, CEO of Echlin and Chair of the Connecticut Hospice Board for many years, championed that move. The numbers were much bigger, but the fundraising, governmental assistance, and other challenges remained much the same. Today, our 52-bed, waterfront inpatient facility provides the peace and serenity that are moving to so many patients and their families.

Dennis Rezendes went on to other endeavors, ending up in Boulder, Colorado. He left us with a rich legacy, as did Florence Wald and her early helpers. So many parts of US, Connecticut, and New Haven history are woven into many stories such as the one above, and they provide a timeline of the changes in our country, our health care system, and our attitudes toward serious illness and death. It is amazing to read about how many interventions and lucky connections took place along the way. The farsighted people who provided leadership in so many other areas were often the same ones who championed our cause along with our predecessors. There are many more than those mentioned here, and we stand on their shoulders. We are, and should be, so grateful to the pioneers who founded The Connecticut Hospice, and, in the process of doing so, transformed end-of-life care for everyone.

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.