Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

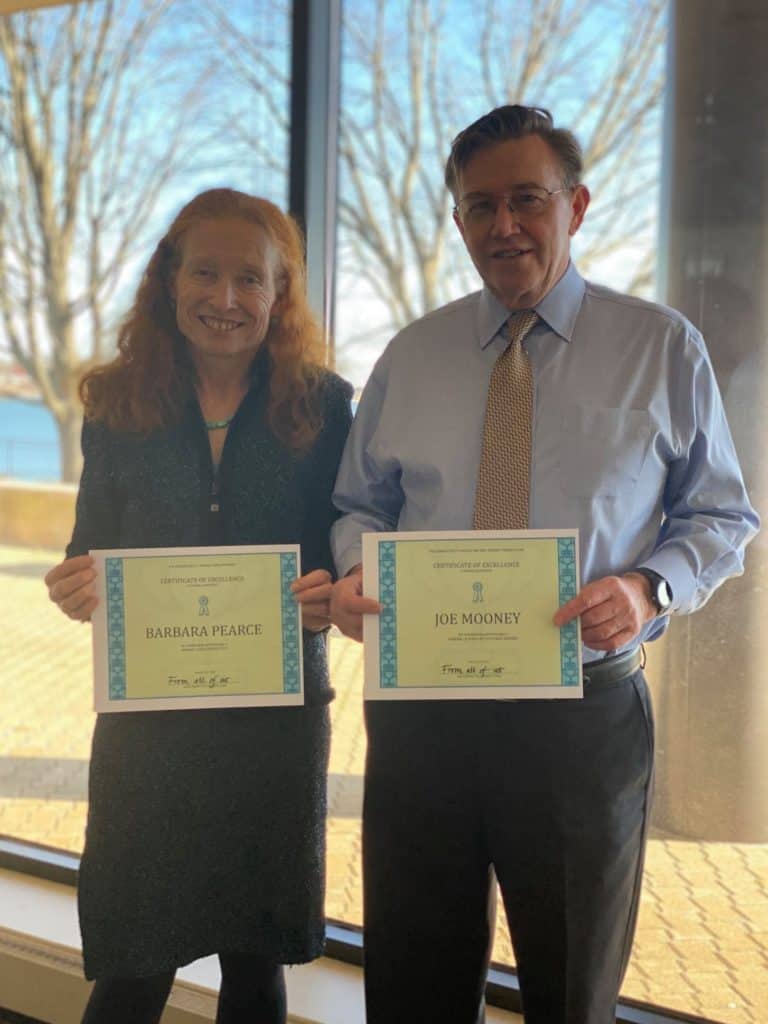

February 1, 2021 marked the 2nd anniversary of new leadership taking over The Connecticut Hospice. It was a relief for the staff when Barbara Pearce, CEO, and Joseph Mooney, CFO, arrived bringing hope for American's 1st Hospice. And, while it is no secret of the mountain of challenges and changes the non-profit has been through over the last two years, it isn't until you hear them spoken out loud that it becomes apparent that Connecticut Hospice is resilient.

In a recent interview, Barbara Pearce, CEO, shared her recollection of her last two years at Connecticut Hospice, with Bruce Tulgan, creator of The Indispensables podcast. Listening to Barbara share the numerous and sometimes grueling challenges the organization has faced during the last two years, it becomes clear why Connecticut Hospice has been around for forty-seven years -- hospice care started at and continues at Connecticut Hospice.

Use link below to hear the full podcast.

The Indispensables Podcast

Conversations with real go-to people who stand the test of time in the real world of work. Based on Bruce Tulgan's new book, The Art of Being Indispensable at Work, The Indispensables is a podcast series about how real people, in the real world, become indispensable, go-to people who stand the test of time at work. For more information, visit Rainmaker Thinking.

"Connecticut Hospice may not be able to add days to your life, but it can certainly add life to your days." -Barbara Pearce

In that time, many things have changed about attitudes toward illness, treatment protocols, and discussions about the end of life, but our mission has not altered. Nor has our consistently high level of compassionate care. We have, however, learned a great deal about how to interact with families and caregivers, and certain misperceptions persist, especially as to expectations about what end of life care at home means.

While interviewing home care nurses for this article, one point came up every time. People think that home hospice care will be 24/7, or at least will be daily help with personal care. Home care means that the family is providing the care, and the hospice team is their support system. We are there to guide, teach, comfort, and counsel, but families do more hands-on care, and administration of medications, than many believe will be true going into the experience. While we try to go above and beyond whenever possible, we cannot take the place of those at the bedside all the time. It’s very hard to see a family member at the breaking point from lack of sleep, stress, and constant vigilance. Although we discuss all this at the time of admission, it’s important to make sure that people understand the limitations of Medicare Hospice Benefits help at the outset.

First of all, we have to certify that the patient meets the criteria for hospice care at home. They are normally bedbound, with a disease trajectory of six months or less, and they are seeking palliative care, not treatment for the disease. Family members should be discussing the prognosis and course of the illness, because the other most common feedback we receive is that they did not begin hospice care early enough. Because of advanced types of treatment, we see patients entering hospice care later and later. A third of the time, they sign up within three days of death, meaning that they cannot take advantage of all of the services we offer.

Many do not know that Medicare Hospice home care, as opposed to palliative home care, pays for equipment, transportation, and medications. On the first day of service, or shortly thereafter, your hospice nurse will order what is needed for that patient’s care. It could be a hospital bed, a walker, or an ambulance ride for certain types of appointments. Because, in this case, it is hospice care that has been chosen, there will not typically be physical or other types of therapy. Hospice care, though, provides more frequent nursing visits, especially in the last few days of life.

You will also be given a comfort pack, as it is often called, to keep in the refrigerator in case of unexpected breakthrough pain. There will be strong painkillers included, the use of which your hospice nurse will walk you through.

Social work is one of those provided services, and many families are hesitant about meeting with a social worker, perhaps thinking that such help would be for family dysfunction. Although that can be true, most social help focuses on practical questions about wishes for the end of life, funeral plans, financial issues, and bereavement offerings by Connecticut Hospice (which are covered by Medicare for 13 months after the end of the patient’s life). We are required to have a social work meeting within a few days of signing on to hospice care, so that our work can begin.

We also offer other types of ancillary services, in addition to the nursing staff. We have aides, who do help with personal care and other such chores. We offer pastoral care and art therapy, sometimes by FaceTime and sometimes in person, depending upon the wishes of the patient and family. We also have volunteers, who do errands, sit by the bedside, or help in other ways. We have a 24/7 number to call with questions, and we urge families to use that number before calling 911, as many hospital visits can be avoided with our advice and attention.

All of the above members of the patient’s care team meet weekly, in a meeting called IDT, for Interdisciplinary Team. This is the heart of our comprehensive support program, where we discuss each patient, and make appropriate adjustments to what is called the Plan of Care. Our Medical Director weighs in, as do the other caregivers. Issues of pain management or possible caregiver overload are addressed, with all members of the staff giving suggestions.

Sometimes we advise families to consider a five-day respite care stay at our Branford inpatient facility, if medications need to be adjusted, or a caregiver needs a break. Those stays are particularly common when there are power outages, which seem to be more frequent with each passing year.

Occasionally, we may advocate that the patient be admitted to our 52-bed, waterfront inpatient facility if such care as is needed is too much to be given safely at home. In many other cases, we can alter medications or change dosages, so that your loved one can comfortably remain at home.

In all cases, we seek to meet the patient’s wishes for his or her end of life, including closure, medication level, and last wishes. We love those last birthday parties, visits, and sometimes weddings! Our staff loves nothing better than to make a wish come true. If a clergyperson is requested, we can take care of that contact.

At the very end of life, your support team will answer questions, make extra visits if needed for symptom management, and provide information about what to expect in the way of behaviors. After the patient has died, a hospice nurse will come to make the pronouncement and will deal with the death certificate for the funeral home. Our social work and bereavement team swings into action as needed, or requested.

The purpose of writing this piece is to help align the expectations and desires of patients and their loved ones with the commitment and capabilities of our dedicated hospice home care staff. Our goal is to make the transition easy and meaningful for everyone involved, just as we have done for all these decades. We want to serve you in the best way possible.

If you have ever wondered, "What happens at hospice?" or, "What to expect for hospice care?" This post will walk you through a day in the life of a hospice.

People have preconceived notions about what hospice life must be like, and it usually involves words like “depressing”, “sad”, or “painful”. Connecticut Hospice, the country’s first hospice and a pioneer in end of life care for almost fifty years, is none of those things.

If one were to walk onto the inpatient floor, very early in the morning, the first impression is one of peace and quiet. There are no beeping machines, overhead lights, or loudly speaking caregivers, that characterize so many other health care institutions. Here, they are still hours from breakfast, with family members who have slept on a cot at the bedside of a loved one roaming the halls, looking for fresh coffee on each end of the floor. Nurses and doctors are whispering morning greetings, and huddling about the patients and their conditions overnight. Everyone who is awake is soon watching another beautiful sunrise over Long Island Sound. No matter the weather, or the season, it’s always a joy to see the sun come up over the water at our 52-bed, waterfront inpatient facility.

On the other floors, home healthcare nurses and aides are picking up supplies, checking in with supervisors, and communing over whatever snacks have been left out by grateful families. Maintenance and kitchen workers are going about their days, while office workers are settling in for the morning. The pharmacy is buzzing with activity, as they calibrate dosages and adjust drugs after the night reports are in. Early birds have begun to churn out their work, while other offices await occupants.

Not everyone wears scrubs, but many do, especially if they interact with patients. Nurses and Certified Nurse Assistants each have special colors, except on Friday, when any color goes. The holidays bring a relaxation of the color rules, and a lot more red and green apparel is seen, along with reindeer headbands. In other departments, people can wear any color, though the current favorite is probably black, which is far more chic than the baggy blue handed out to staff. One such fashion plate has even had his monogrammed!

9 AM is midmorning for some, but many other people are still arriving. The official start of many homecare days is the IDT meeting. That stands for Interdisciplinary Team, which is what Medicare requires for care coordination. Our comprehensive approach to hospice and palliative care is delivered by a medically directed, nurse-coordinated, interdisciplinary team, which consists of hospice and palliative board-certified physicians, nurses and pharmacists.

Despite its being required, many professionals have come to love the IDT meetings. Much of their time is spent on the road and working alone with patients and families, so they value the camaraderie and mutual support of the IDT. Teaching also takes place, with doctors and supervisors sharing medical knowledge or regulatory updates. The meeting can last for two or two and a half hours, after which everyone rushes off to begin daily home and nursing home visits. Once a week, the inpatient care team holds the same IDT meeting, where colleagues who do work together every day pause to consider treatment options and suggestions.

By midmorning, visitors have begun to arrive. The front desk is staffed all day and evening, often by volunteers. They kindly greet each arriving party, explain the CT Hospice rules (especially during COVID), and comfort those waiting for a turn to go upstairs. Sometimes the lilting music of a grand piano drifts down the entrance hallway, where a volunteer plays for those who gather. It is not unusual to see a wheelchair or a bed rolled in for an impromptu or planned concert.

Those who work in support capacities are in full swing, paying bills, raising charitable funds to supplement Medicare reimbursements, hiring new staff members and volunteers, keeping track of all the rules and regulations that govern a hospice’s existence.

On nice days, families often take their loved ones outside. All the beds can be moved, and there is often a staff member or volunteer to help a patient who wants to be in the sunshine, but doesn’t have someone visiting. Small groups can be seen outside around the beds, at picnic tables scattered over the rolling lawn, or in the gazebo down by the double beach that gives the street its name. At high tide, that beach disappears, but, at low tide, family members can be spotted climbing on the rocks and enjoying the view. Raised flower beds grace the exit doors, reminding everyone of the circle of life.

Lunchtime for patients happens as one would imagine, with trays delivered to beds. It’s not uncommon, however, to see a peach, some potato chips, or another treat sent up from the kitchen for a patient with a sudden craving. Some visitors bring favorite foods or drinks, while others (including staff), use delivery services from nearby restaurants. The staff eats on a separate floor, where the table is often piled with goodies brought by family members, or donated by outside groups. Halloween and Christmas both involve lots of extra calories!

All afternoon, there is a steady stream of ambulances delivering patients, or transporting respite patients back home. Each new arrival is greeted efficiently and compassionately. Those who enter in pain are usually made comfortable right away. By then, the evening shift has taken over, and new nurses and CNAs are checking on patient comfort levels, calling family members with updates, or attending to documentation on rolling computer trays.

Music and art therapists are going bed to bed, helping patients with requests or just easing loneliness. They have made videos for loved ones, collages, sketches, or other mementos. They help make Facetime calls to relatives, on iPads there for that purpose and play music that releases and relives old memories. Volunteers are also in full swing, either sitting quietly with those resting or wanting silence, chatting with others wishing for company, or playing music in the hallways. Some bring pets trained for visitation in hospitals, and they are particular favorites of everyone! Pastoral care professionals and volunteers visit each bedside, arrange for outside clergy when requested, pray with families, offer use of the prayer room tucked away down a side hall, or hold services in the common room.

As the sun sets, people pause to mark its beauty over the horizon, and begin winding down. Visitors still come, at all hours of the day and night, and the building is open around the clock. Cots are brought for those who plan to stay overnight. Clerical and support staffs head home, and the activity level goes down. People are still admitted during the off hours, but most are there, ready to be tucked in for the night.

And what of the patients in the beds? How does all of this activity affect them, in their final days? As many people have noted, at the end of life the days left are short, but the hours can be long. Decreased mobility, motivation, or purpose can diminish quality of life during a terminal illness. Volunteers, therapists, social workers, clergy, and medical staff all strive to help patients achieve closure, whatever that means for them, find peace, and eliminate pain and fear. To an astonishing extent, they succeed in that mission most of the time. Patients live fully until the end of their time, and find meaning and enjoyment wherever possible. As one patient famously said, “I came here to die, and I learned how to live.” They are the center of the hospice community, and they bask in that attention and concern.

Elsewhere in the facility, workers are still cleaning, cooking, fixing things, writing reports, and getting ready for the next day. Someone is always around, answering the phone for anxious family questions, dealing with crises in home care or in other settings, or completing yet another written report. Sometime during the night, someone changes the mat in the elevator to display the next day’s name (today is Wednesday), and another day begins, softly and lovingly.

When my first daughter was born, a friend noted: “your capacity for grief has greatly and suddenly expanded.” And it had. The friendship, love, pride and the beauty of certain moments – whether or not we notice them in the moment -- are the fruits of our close relationships. As these treasures mount, so does the potential pain we will feel when suddenly that loved one is gone. As for me, I suppose my own capacity for grief has skyrocketed since that day – which also means there are more people (and a dog) in my life with whom I have strong and loving ties.

We observe mourning rituals because they are personally and culturally important and because we need a script to follow when we are in such unfamiliar territory. Those actions – funerals, wakes, shivahs, burials and unveilings -- represent our external, “public” expressions of loss.

We also have an internal experience, called grief. Unlike mourning, grief does not follow a timeline, or have an end date. Grief is often called a journey, and aptly so.

In one sense, we travel through grief as we experience its different stages, including the grief we start to feel even before the loss. Interestingly, the word “hospice” in medieval times referred to a way station for travelers . . . a place providing sanctuary for footsore and weary pilgrims.

Grief also feels like a constant companion – often a quiet one, sometimes disruptive, sometimes a comforting, and wholly unpredictable.

When my sister died I indeed paid the steep price of love. And I experienced grief as both the trip, and the companion. I have noticed the change in how I feel the pain, more a dull ache now than a sharp pain – and I have felt sad, even guilty and almost disloyal about that. That is the trip I am on.

I also have sudden realizations, like understanding that some of my memories were only shared between the two of us, that no one else would understand. Or that our common traits and quirks are now just mine. I think about how she would have handled pandemic times, what we would have decided about coloring our hair, and how we might talk about politics. Or I will stare at her photo and have a little conversation or a laugh. These make up the grief companion I travel with.

During this time of pandemic, the mourning and grief of the bereaved are layered with the tremendous emotional impact of current circumstances. Survivors of one who has died in isolation due to pandemic restrictions, may feel not only profound grief but also trauma from their loved-one’s rapid decline, their inability to comfort them, and not being with them as they died. Trauma is what happens in the brain when an individual experiences something that takes them beyond their normal emotional coping capacity. Experiencing trauma includes symptoms such as anxiety and flashbacks, and it interrupts the normal grief process.

I believe that many bereaved during these past months have, at best, a shaky foundation for moving through their grief. To those who feel unmoored and alone, I offer sincerest hope that they will find stability to start their journey, and happy memories to keep them company along the way.

The Bereavement Program at Connecticut Hospice is a resource for those bereaved who need grief support after the loss of a loved one under our care. It has become quite apparent that the grief that our bereaved are dealing with has been complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The fact is that many friends and family members, who were unable to visit their loved ones at all, due to the visitor restrictions for hospitals, nursing homes and assisted living facilities, had not seen their loved ones for months prior to admission to Connecticut Hospice in Branford. This has become part of the grieving process for many bereaved, unable to comfort their loved ones, or be the advocate at the bedside. The bereaved we are caring for are grieving what feels to be layers of emotion related to the unexpected crisis of the COVID pandemic in addition to the grief related to the death of their loved one. The Connecticut Hospice Bereavement Program continues to navigate this journey with the bereaved, providing comfort and support during a very difficult time, including group meetings. For more information, call Jennifer Stook, Director of Bereavement Services, at 203-315-7544 or visit www.hospice.com/bereavement-program.

Every September, the Connecticut Hospice community of patient families, friends, and caregivers gathers to celebrate and remember loved ones who passed away during the previous twelve months. Connecticut Hospice understands the special importance of this year's event (honoring patients lost 8/1/19 - 7/31/20) as a safe opportunity to gather while also providing closure for families and friends who might not otherwise have had the chance during this challenging year.

Connecticut Hospice is proud to invite you to its first live, virtual event. This event is not just for Ct Hospice families but for all those struggling with loss. Please share this event with anyone you think may benefit. Simply click on link below to bring you to our YouTube channel.

Ceremony of Remembrance Sunday, September 13th at 4 pm via our YouTube channel:

This link will also be available on our website @ www.hospice.com and Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/CTHospice

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/stress-coping/grief-loss.html

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/supersurvivors/201909/the-power-rituals-heal-grief

Caring for patients in a hospice setting is a nurturing and supportive effort that draws on the expertise of professionals engaged in many disciplines, ranging from medical to therapeutic. Indeed, the services offered by a leading hospice, such as The Connecticut Hospice, may in fact be broader and the care offered patients more varied than what is typically pictured by members of the public.

Even so, hospice-service providers remain concerned about the number of persons accessing hospice care late in the course of an illness. That’s per a new report issued by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO), which states that “53.8 percent of Medicare beneficiaries received hospice care for 30 days or less in 2018.”

More telling, is that fully a quarter (27.9 percent) of the beneficiaries received care for seven days or less— which NHPCO considers “too short a period for patients to fully benefit from the person-centered care available from hospice [providers].”

“This annual report provides a valuable snapshot of hospice care access and care, and also a reminder that we must continue to strive to make hospice care more equitable and accessible,” said Edo Banach, NHPCO president and CEO, in a statement. “It is also important to remember that behind these numbers are people who rely on person- and family-centered, interdisciplinary care to help them during a time of great need.”

Of compelling interest to hospice patients and their family members and friends are sections within the full 26-page report on what hospice care entails, how and where that care is delivered to patients, and what are the levels of care provided.

“Hospice focuses on caring, not curing,” NHPCO observes. “Considered the model for quality compassionate care for people facing a life-limiting illness, hospice provides expert medical care, pain management, and emotional and spiritual support expressly tailored to the patient’s needs and wishes. Support is provided to the patient’s family as well.”

The report also points out that, in most cases, “care is provided in the patient’s home but may also be provided in freestanding hospice facilities, hospitals, and nursing homes and other long-term care facilities. Hospice services are available to patients with any terminal illness or of any age, religion, or race.”

Indeed, the term “hospice” is somewhat elastic. It describes any approved provider of hospice services, including those that operate free-standing hospice inpatient hospitals and those that bring hospice care directly to patients where they are, be that a long-term care facility or in their own home.

The Connecticut Hospice (also known as CT Hospice) fits both descriptions, as it operates its own hospice hospital in Branford and fields teams of hospice medical professionals and caregivers to provide services at other caregiving facilities where patients are residing or right in the patients’ homes.

When hospice services are provided as in home, a family member typically serves as the primary caregiver and, when appropriate, helps make decisions for the terminally ill individual, notes NHPCO. “Members of the hospice staff make regular visits to assess the patient and provide additional care or other services. Hospice staff is on-call 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The hospice team develops a care plan that meets each patient’s individual needs for pain management and symptom control.”

An interdisciplinary hospice team usually consists of the patient’s personal physician, hospice physician, nurses, hospice aides, social workers, bereavement counselors, clergy or other spiritual counselors, trained volunteers, and speech, physical, and occupational therapists, if needed.

NHPCO lists these as interdisciplinary team services:

Nancy Peer, an Associate Professor for Hospice and Palliative Care at Central Connecticut State University, secured a bed for her son, Brian, who was dying of testicular cancer, so he could live out his last weeks at CT Hospice. “Every nurse that came in was not only compassionate… they would see how our son was doing and then they wanted to know how they could help us,” Peer recently told the Daily Nutmeg of New Haven.

Peer said that during the week Brian spent at the hospice, before dying at age 39 and leaving behind his wife of one year and his parents and a younger brother, friends and extended family were able to visit him and Peer and her daughter-in-law stayed with him. She remarked that the help he and his family received from CT Hospice was “priceless.”

The NHPCO report also details the four Levels of Care (as defined by the Medicare hospice benefit) that hospice patients may require. The levels are distinguished by the intensities of care provided relative to the course of a given patient’s disease.

“While hospice patients may be admitted at any level of care, changes in their status may require a change in their level of care,” NHPCO explains. “The Medicare Hospice Benefit affords patients four levels of care to meet their clinical needs: Routine Home Care, General Inpatient Care, Continuous Home Care, and Inpatient Respite Care.”

The report rightly credits the significant positive impact of hospice-care volunteers. “The U.S. hospice movement was founded by volunteers” and they “continues to play an important and valuable role in hospice care and operations.”

But volunteering is not a simple matter of stepping up to help others. The Connecticut Hospital, for example, requires that prospective volunteers receive a background check before coming onboard and then they are professionally trained by hospice staff to provide care and assistance to patients and their loved ones.

The importance of volunteers is underscored by NHPCO’s observation that “hospice is unique in that it is the only provider with Medicare Conditions of Participation requiring volunteers to provide at least 5% of total patient care hours.”

Volunteers typically provide service to others in these three general areas:

Spending time with patients and families (“direct support”)

Providing clerical and other services that support patient care and clinical services (“clinical support”)

Engaging in activities such as fundraising, outreach and education or serving on a board of directors (“general support”)

For information on volunteer opportunities with The Connecticut Hospice, please go to our website, www.hospice.com, or contact Joan Cullen at [email protected] or 203-315-7510.

The Connecticut Hospice is America's first hospice. It was founded by Florence Wald, and a group of nurses, doctors, and clergy, in 1974 and was the first of its kind in the United States. A few years prior, Wald, then an Associate Professor and Dean of the Mental Health and Psychiatric Nursing Program at Yale University, was inspired by a palliative care lecture given by Dr. Cicely Saunders, the founder of St. Christopher’s Hospice, the first hospice in the world.

Today, CT Hospice’s services encompass both in-home and inpatient care for persons diagnosed with a terminal illness with a limited prognosis, normally of six months or less.

The Connecticut Hospice’s central commitment is to enable the patient to live as fully and completely as possible during the time of their illness. This includes supporting the entire family as the unit of care, rather than just the patient. For example, home-care programs are designed to make it possible for families to keep the patient at home if such care is appropriate, and to marshal community resources to help deepen support and keep care costs as low as possible.

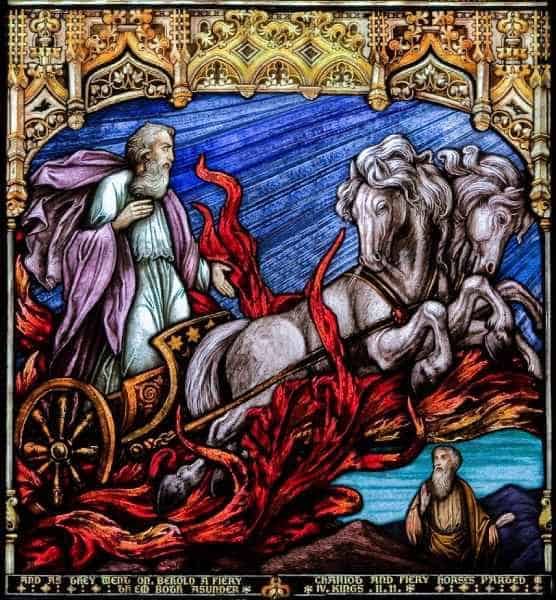

About an hour after my father died, I wandered away from my parents’ den, where he lay in a rented hospital bed, and went outside to be by myself for a while. On the horizon of the cold dusk sky the January sunset was a deep blazing red, more vivid than I remember seeing before or since. I imagined Dad shooting through the sky like a flaming arrow, for he was straight and true. Or like the Greek sun-god Helios arcing across the firmament in his chariot, for he was like the sun to me. Or Old Testament Prophet Elijah spiraling up to heaven in his fiery chariot, for Dad had (briefly) suffered, and deserved this final reward. Or all of these things at once.

These images were felt by me instinctively, and I didn’t share them with my mother, my sister or my daughter - partly because they were so intense I didn’t feel I could speak them aloud, and partly because a little internal voice said that I might be perceived as being melodramatic or even superstitious. Dad was an atheist, besides, and an academic family such as ours generally needed provenance, logic, or science to believe such things, surely?

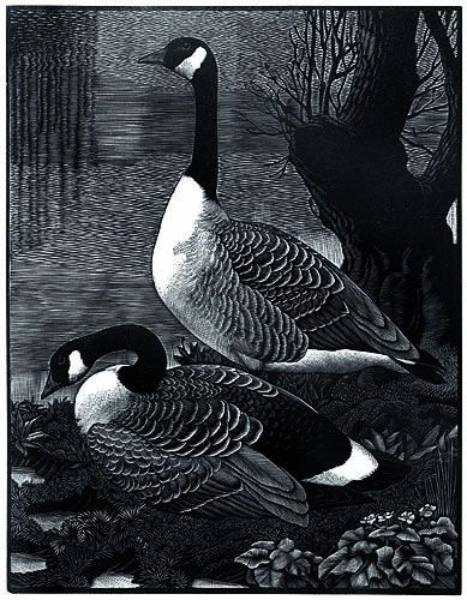

It turned out that we needed none of those things, and a few hours later any doubts I had of such ideas were firmly swept away. Sitting in the dark on the family porch, I was startled by a lone goose, who flew down unusually close to the house, only honking when right in front of me, and then flapped away. It felt like a visit, and I went inside to tell my family about this “amazing phenomenon” before returning outside to the still night air.

About half an hour later Mum came to join me, and literally as she stepped through the door, a chevron of geese swooped down lower than any ever had before, all honking wildly as they flapped by. This had to be a sign, right? Lo and behold, when my sister came out to look for us another half hour later, yet one more goose suddenly appeared out of nowhere to make its presence known.

We all clung to the belief that this had to mean something, because believing the geese were visiting for a reason, that they might even be Dad saying goodbye, brought us comfort in that bleak “dark night of the soul”.

Since then, half the birds of the northern hemisphere’s skies have become ‘symbols of Dad’, such is our wish to remain connected to him in as many ways as possible. My sister and I have talked about this – she lives thousands of miles away, on another continent, and yet she sees the same ‘signs’.

For me, noble hawks always seem to circle overhead when I need his strength;

bright, persistent cardinals pop up in the nearby hedgerow when I want to chat to him;

mated-for-life swans scud silently by to remind me of his marriage proposal to my mother on the second day they met (married five weeks later, they were soul mates for 60 years);

never-shy catbirds hop right up close and train their beady eye on me in the same piercing way Dad always did;

squabbling blue jays even bring back family silliness, when we were a family together;

ephemeral, iridescent hummingbirds are rare and colorful visitors to my yard, but he was rare and colorful too.

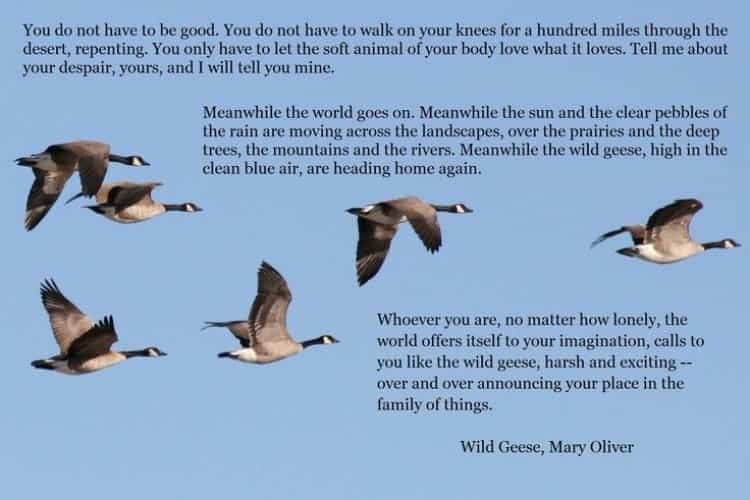

And the seminally symbolic geese always bring me right back to the seismic shift in our world on that evening, when at one moment he was alive with us and in the next he had wrenched himself away.

Accepting and allowing that he was gone, in intensely painful slow motion, was like a long difficult labor, delivering a new reality.

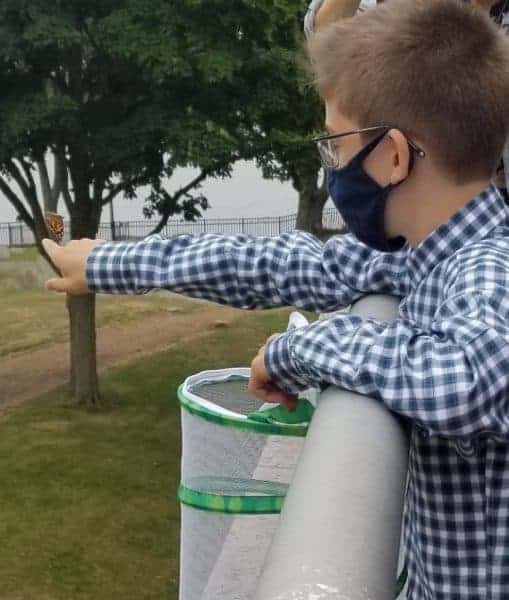

Why do human beings believe that signs and symbols from the natural world represent the presence of, or messages from, our loved ones after they are gone? For instance, many people believe that butterflies are deep and powerful representations of life. Butterflies are often thought to be a symbol of their departed loved ones or of eternal life, perhaps because of their metamorphosis from chrysalis to butterfly. Recently, Dmitri, a Connecticut Hospice staff member’s son, felt it was symbolic to release the 6 new butterflies from his Butterfly Garden on the site where hospice care first began in the United States.

Dragonflies are said to symbolize change and transformation, and are connected to signs from loved ones. Feathers, storms and rainbows are also often imbued with special meaning after a loss.

There are websites devoted to supporting the bereaved through the sharing of personal stories of ‘signs and symbols’ they have experienced. Click here for an example: signs of a deceased loved one

People often tell the recently bereaved to “look for signs – you’ll see them all around”, to reassure and comfort, and because they believe it to be true.

It seems that we try to hold onto someone we dearly miss by creating a physical manifestation where there is no longer a physical presence. That so many of these ‘messengers’ are animate entities of the natural world – animals, birds, insects, sometimes even flowers and trees – appears to bear this out.

It is well documented that nature has the power to bring solace and rejuvenation to us whether or not we are grieving, and it is plausible that we instinctively understand this capacity when we so readily ascribe special meaning to its creatures and its beauties.

Nick Cave writes

“The paradoxical effect of losing a loved one is that their sudden absence can become a feverish comment on that which remains. That which remains rises in time from the dark with a burning physicality — a luminous super-presence — as we acquaint ourselves with this new and different world. In loss things – both animate and inanimate – take on an added intensity and meaning”.

Nowadays, when Mum and I sit on the porch together, we sometimes talk about the ‘Great Creative Force” that connects all things. As an artist and woman of great wisdom, my mother can find symbolism and interconnection everywhere. Where once the anecdotes we heard about ‘signs’ from departed loved ones were possibly feasible, but mostly abstract, ideas, our family now knows and feels the truth of them.

We lost him but now he is everywhere.

Further resources:

To read Nick Cave's entire piece, click here: how to understand the experience of loss

To read an essay on birds and loss, visit: the birds scattering blue

What is the 'dark night of the soul'? To explore its interpretations, click here: the dark night of the soul - understanding amidst the absence of meaning

To hear the exquisitely beautiful "Dark Night of the Soul", Ola Gjeilo's composition for chamber choir, piano and string quartet (approx. 13 minutes), watch: Youtube: Dark Night of the Soul, Ola Gjeilo

Learn about and listen to catbird songs: All About Birds: Gray catbird sounds

All about Helios and how he is different from Apollo: Wikipedia: Helios

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.