Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

In the ever-evolving landscape of medical education, institutions that prioritize hands-on experience, interdisciplinary collaboration, and compassionate care are invaluable. The Connecticut Hospice stands out as a beacon of excellence, offering a myriad of educational opportunities for pre-med students, medical students, residents, and fellows. This blog post will delve into the educational programs provided by The Connecticut Hospice through the John D. Thomas Institute and shed some light on how they contribute to the development of well-rounded and empathetic healthcare professionals.

Before delving into the educational offerings, it's essential to understand the foundation upon which The Connecticut Hospice stands. Established in 1974, it holds the distinction of being the nation's first hospice. Its mission revolves around providing patient-centered, end-of-life care rooted in compassion, dignity, and respect. This commitment to holistic care forms the backbone of the educational opportunities offered.

The John D. Thompson Hospice Institute for Education, Training and Research, Inc. (JDT Institute), the educational ally of Connecticut Hospice, was established in 1979, when it gave its first educational conference. The JDT Hospice Institute is a vehicle for sharing the hospice philosophy with all who desire to improve the quality of care for patients (and their loved ones) experiencing an irreversible illness. It offers opportunities for students, health care professionals, administrators, caregivers, and the lay community to learn, and gain experience and skills in hospice care.

At the core of good hospice care is the interdisciplinary team approach. Every patient is cared for by a team that includes medicine, nursing, social work, spiritual, bereavement, pharmacy and volunteers. The team ensures the patient receives care at the physical, mental, and/or emotional levels, if and when needed during their journey. Connecticut Hospice offers clinical rotations in medicine, nursing, social work, and pharmacy.

Traditionally the first milestone in the long journey to becoming a practicing healthcare provider is usually shadowing other providers. Here at Branford, we offer extensive shadowing opportunities. Students can observe seasoned healthcare professionals navigating the challenges of end-of-life care, learning not only medical procedures but also the nuances of compassionate communication both in our inpatient unit as well as with our homecare team. Recognizing the importance of early exposure to hospice and palliative care, The Connecticut Hospice offers pre-med programs designed to ignite the interest of aspiring healthcare professionals and expose them to the realities of practicing medicine in our current healthcare system as well as mentor them to the requirements of applying to graduate professional programs.

Students approved to complete clinical hours at The Connecticut Hospice are afforded a unique and enriching experience. Although many come from schools in the Northeast, the opportunities to rotate here are open for all institutions across the country. The institution recognizes the importance of exposing future physicians, nurses, social workers, art therapists, music therapists and pharmacists to end-of-life care, fostering empathy, and refining communication skills. Through structured programs, students have the chance to shadow experienced practitioners, and engage in patient care activities under the guidance of experienced mentors. This hands-on experience allows them to apply theoretical knowledge in a real-world setting, honing their clinical skills and deepening their understanding of the unique challenges in end-of-life care.

Throughout COVID, and the nursing shortage, Connecticut Hospice worked with area nursing programs to provide clinical practice hours that were standing in their way of graduating and joining the dwindling nursing pool. Yes, it is about teaching how to provide good hospice and palliative care, but it is also about sharing the importance of both hospice and palliative care in the cycle of terminal illness.

The Connecticut Hospice places a strong emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration. Learners here actively participate in rounds that bring together physicians, nurses, social workers, and other healthcare professionals. This approach provides a holistic view of patient care, fostering an understanding of the diverse skills required in end-of-life medicine.

For medical residents seeking to specialize in palliative care or related fields, The Connecticut Hospice offers comprehensive clinical exposure to end of life medicine. Residents may come from any ACGME accredited program and specialty. These programs provide a structured curriculum that combines clinical experience, research opportunities, and mentorship in a variety of inpatient and outpatient settings. Rotating residents at The Connecticut Hospice benefit from a diverse range of clinical experiences. From managing complex symptoms to leading family meetings, residents are actively involved in the care of patients facing life-limiting illnesses. This exposure equips them with the skills necessary for providing compassionate and effective end-of-life care.

Students earning an advanced degree in nursing, social work, art therapy, music therapy or pharmacy spend a significant amount of time at Connecticut Hospice, quickly becoming a member of the care team and gaining unique experiences from collaborating care.

Social Workers pursuing a Masters spend their entire final year with us, allowing them the opportunity to learn from a seasoned social worker how to best guide a patient and their family through one of the most stressful events of life, death of a loved one. There are so many factors to consider when caring for a family unit, especially when death is at the core. It takes time for a social worker to become comfortable with the unique needs of a hospice population and the extended time allows for learning and experiencing from the seasoned social worker.

The JDT institution encourages learners across the spectrum of academia to engage in research projects that contribute to the evolving field of palliative care. By collaborating with experienced researchers and faculty members here at the Connecticut Hospice, learners get the opportunity to explore innovative approaches to symptom management, psychosocial support, and ethical considerations in end-of-life care and receiving the structured mentorship to pursue their own individual projects.

Every PharmD candidate who completes a month-long rotation with Connecticut Hospice’s onsite Pharmacy Department is required to present findings on a pharmacological topic selected prior to the start of their rotation. The findings are presented on the student’s final day to members of the interdisciplinary team who were all part of the learning experience. The collaboration between a student and those with heavy experience can create something great.

Mentorship plays a pivotal role in the residency programs at The Connecticut Hospice. Our learners work closely with our seasoned professionals who provide guidance not only in clinical matters but also in navigating the emotional and ethical dimensions of palliative care, as well as preparing for the next step in their own professional journeys.

If clinical medicine isn’t desired, The Connecticut Hospice also can offer unique individualized internships with our senior management and executive teams. Rotating through our non-profit and working directly with our executives provides the learner with a special opportunity to collaborate closely on business development plans and network with regional partners.

The Connecticut Hospice's offers tailored programs and educational workshops that cover the basics of palliative care, hospice care, pain management, and the psychosocial aspects of end-of-life care. These workshops serve as a bridge between classroom learning and practical application in the community. We offer these experiences and lectures to our community partners and travel to them to deliver these interactive and informative sessions.

In addition to the above, The Connecticut Hospice offers a robust and enriching volunteer experience. These hands-on experiences allow each person to donate their time and/or talent to our patients in a multitude of ways. Each new academic year provides Connecticut Hospice with more than 75 medical students looking to volunteer to gain experience working with patients and families. These future healthcare providers create a positive energy that fills the building. In addition to these medical students, Connecticut Hospice is always in need of volunteers to share their talents with us. If you or your organization is interested in volunteering, please reach out to our Director of Volunteers at [email protected].

The educational opportunities offered by The Connecticut Hospice form a critical component of the institution's commitment to advancing the field of hospice and palliative care. No matter what a student’s ultimate position is in healthcare, Connecticut Hospice encourages them to take the unique experiences offered at America’s first hospice to enable them to be the best they can be throughout their career. By combining hands-on experiences, interdisciplinary collaboration, and a commitment to compassionate care, The Connecticut Hospice is shaping the next generation of healthcare professionals who will navigate the complexities of end-of-life medicine with skill, empathy, and resilience. As we look toward the future of healthcare, the lessons learned at The Connecticut Hospice serve as a guiding light for those dedicated to providing dignified and compassionate end-of-life care.

For more information on clinical rotations at Connecticut Hospice, email [email protected].

Dementia is a complex and debilitating condition characterized by cognitive decline, memory loss, and impaired daily functioning. As the disease progresses, patients often reach an advanced stage where their functional abilities decline significantly. The Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST) serves as a valuable instrument for assessing and staging the progression of dementia, particularly in its advanced stages. This blog post aims to delve into the FAST, elaborate on the score needed for hospice eligibility, describe common characteristics of end-stage dementia, and touch upon different types of dementia and highlight how the decline can vary among these types.

The Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST) is a widely recognized and validated instrument used to assess the functional abilities of individuals with dementia. It was developed by Barry Reisberg, MD, and his colleagues in the late 1980s to provide a structured framework for staging the progression of Alzheimer’s dementia based on functional impairment. The FAST consists of seven stages, each representing a distinct level of cognitive and functional decline.

| FAST Score | Dementia Stage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | No Cognitive Decline | Normal cognitive function and memory. No observable symptoms of dementia. |

| Stage 2 | Very Mild Cognitive Decline | Slight cognitive changes attributed to aging. Forgetfulness and mild difficulty finding words. |

| Stage 3 | Mild Cognitive Decline | Noticeable cognitive impairment. Frequent memory lapses. Challenges in work or social settings. |

| Stage 4 | Moderate Cognitive Decline | More pronounced cognitive deficits. Intensified memory loss, reduced problem-solving, and attention. |

| Stage 5 | Moderately Severe Cognitive Decline | Significant cognitive and functional deficits. Memory deterioration, confusion about time/place. |

| Stage 6 | Severe Cognitive Decline | Profound cognitive impairment. Difficulty recognizing loved ones, memory loss, personality changes. |

| Stage 7 | Very Severe Cognitive Decline (Subclassification A-F) | Total functional dependence. Challenges in mobility, communication, and basic tasks. |

| 7A | Speaks 5-6 words during the day | Limited verbal communication ability. |

| 7B | Speaks only 1 word clearly | Severely restricted verbal communication. |

| 7C | No longer can walk without assistance | Mobility challenges, walking assistance required. |

| 7D | Can no longer sit up | Inability to sit up unassisted. |

| 7E | Can no longer smile | Loss of ability to smile. |

| 7F | Can no longer hold their head up | Inability to hold head up without assistance. |

The FAST score assists healthcare professionals, caregivers, and families in assessing the level of cognitive and functional decline, enabling them to provide appropriate care and support tailored to each stage. By understanding the implications of each stage, individuals can ensure the best quality of life for those living with Alzheimer’s dementia while navigating the challenges that arise throughout its progression. It's important to note that while the FAST provides a structured framework for understanding Alzheimer’s dementia progression, the exact experience can vary among individuals. Additionally, the rate at which individuals progress through the stages may differ based on factors such as the type of dementia, overall health, and individual characteristics.

Hospice care is a specialized form of medical care aimed at providing comfort, support, and quality of life for individuals with life-limiting illnesses, including advanced dementia and neurocognitive disorders. Determining hospice eligibility involves a comprehensive assessment of the patient's medical condition, functional status, and prognosis. The Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST) score, along with Medicare's Local Coverage Determination (LCD) for dementia and neurocognitive disorders, plays a significant role in determining hospice eligibility for individuals with these conditions. Generally, a FAST score of 7A or higher is considered indicative of end-stage dementia, indicating that the individual's cognitive and functional impairments have reached a point where specialized end-of-life care is necessary.

Individuals with a FAST score of 7A or higher often require assistance with most, if not all, activities of daily living (ADLs). These activities may include eating, dressing, bathing, toileting, and mobility. Additionally, they may experience communication challenges, memory loss, and an overall decline in cognitive abilities. The FAST score helps healthcare professionals, caregivers, and families make informed decisions regarding the appropriate level of care, including hospice services, to ensure the individual's comfort and well-being.

Medicare, the federal health insurance program in the United States, covers hospice services for eligible beneficiaries. Medicare's Local Coverage Determination (LCD) provides guidelines for determining hospice eligibility based on the specific medical condition, prognosis, and functional status of the individual. For individuals with dementia and neurocognitive disorders, the LCD outlines the criteria that need to be met for hospice coverage.

The LCD typically includes criteria related to cognitive impairment, functional decline, and the overall trajectory of the disease. It may require documentation of a qualifying FAST score, indicating the individual's advanced stage of dementia. Additionally, the LCD may consider other factors such as recurrent infections, declining nutritional status, and overall decline in medical condition. Meeting these criteria ensures that individuals receive the appropriate level of care, focusing on comfort and symptom management.

Dementia is an umbrella term that encompasses several types of neurodegenerative disorders, each with its unique characteristics, underlying causes, and progression patterns. Understanding these different types of dementia is necessary for providing appropriate care and support to individuals affected by the condition. Let's delve into the various types of dementia and their distinct features:

Each type of dementia presents its unique challenges and progression patterns. Understanding the differences is crucial for accurate diagnosis, effective management, and tailored care plans. Healthcare professionals, caregivers, and families must be knowledgeable about these variations to provide the best possible support and enhance the quality of life for individuals affected by dementia. Early diagnosis, appropriate interventions, and compassionate care play vital roles in improving the well-being of those living with dementia and their loved ones.

In the realm of dementia care, hospice services emerge as a beacon of compassion and comfort, providing a sanctuary for individuals navigating the challenging journey of advanced dementia. Hospice care becomes an essential companion during this critical phase, offering specialized support that enhances both the quality of life of patients and the emotional well-being of their loved ones. As individuals with advanced dementia face the formidable decline in cognitive and functional abilities, hospice steps in to offer solace, dignity, and a comprehensive approach to care that is as empathetic as it is effective.

For patients with advanced dementia, hospice services serve as a lifeline, offering tailored care that focuses on pain management, symptom relief, and emotional well-being. Hospice professionals possess a deep understanding of the nuanced needs of individuals in end-stage dementia, providing expert guidance to alleviate discomfort, anxiety, and distress. Through carefully designed interventions, hospice services enhance patients' comfort, fostering an environment of tranquility that nurtures their dignity and humanity. The holistic care approach encompasses not only the physical aspects of care but also addresses the emotional and psychological well-being of both patients and their families.

Loved ones of individuals with end-stage dementia can find solace in the embrace of hospice care, as it offers not only practical support but also a compassionate presence during this profoundly challenging period. Hospice teams work closely with families, helping them navigate the complexities of dementia care, offering respite, education, and emotional guidance. Family members can expect a multidisciplinary team that includes nurses, doctors, social workers, counselors, and volunteers, all dedicated to creating a nurturing environment that preserves the dignity and comfort of the patient. As the progression of dementia can be emotionally demanding for families, hospice also provides much-needed psychological support, helping loved ones cope with grief and make the most of the time they have left with their cherished family member.

In the realm of dementia care, hospice services shine as a beacon of compassion and empathy. Through their expertise, dedication, and unwavering commitment, hospice professionals offer patients with advanced dementia the opportunity to transition with grace, comfort, and respect. Families can expect not only comprehensive care for their loved ones but also a support system that holds their hands through the challenges of end-stage dementia. In the final chapter of the dementia journey, hospice care becomes a testament to the power of human connection and compassion, reminding us that even in the face of decline, every individual's story deserves to be honored and cherished.

No matter your age or health status, a properly executed Advance Directive is essential to assure you receive healthcare that aligns with your beliefs and wishes. Even the young and healthy may find themselves in an unanticipated medical situation in which an Advance Directive is critical.

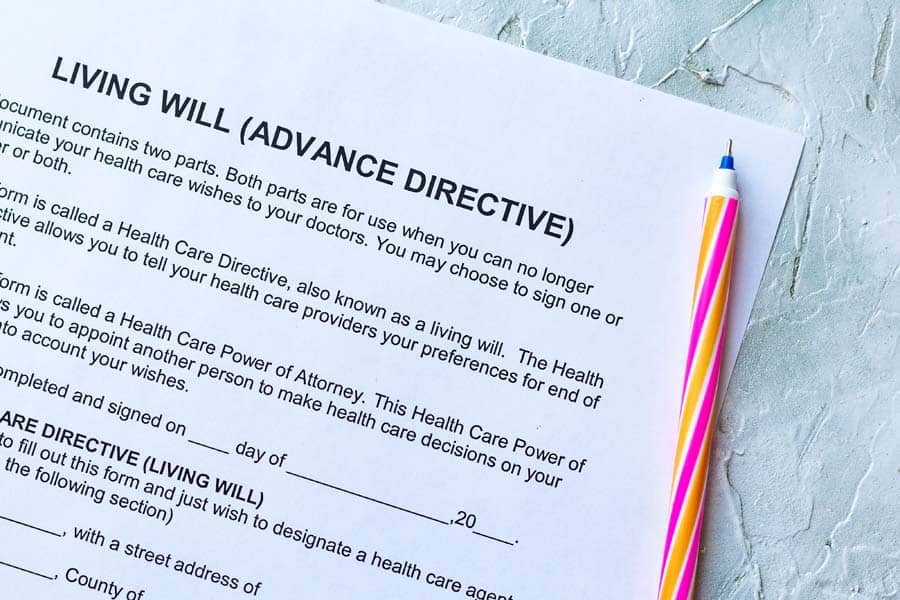

An Advance Directive is a legal document that allows you to maintain control over the healthcare you receive should you be in a circumstance where you are unable to communicate your wishes to your healthcare providers.

Which Advance Directive to choose depends on your wishes, your understanding of the limitations of each type of Advance Directive, and your state of health. First, let’s review the healthcare representative. Before we do, though, some confusion about this form of Advance Directive needs to be cleared up. In addition to the term “healthcare representative,” you may also hear the phrases “healthcare agent,” and “durable power of attorney for healthcare.” Each of these is essentially the same, and Connecticut officially replaced the latter two terms with the former on October 1, 2006. In keeping with this, I will use “healthcare representative” going forward to refer to this form of Advance Directive.

A healthcare representative is legally designated by an individual to make their healthcare decisions should they no longer be able to communicate — for example, they are unconscious and cannot talk or write. In contrast to the other types of Advance Directive, a healthcare representative offers the most flexibility in directing doctors and other healthcare workers no matter the now-incapacitated person’s medical circumstance. A Living Will cannot be honored unless specific criteria are met and may not allow medical providers reasonable flexibility in the care they provide (discussed below). A Connecticut MOLST is also very specific, and is only legally used for people with serious illness (also discussed below).

Designating a healthcare representative is easy and does not require a lawyer or Notary Public. Your healthcare representative should be a person — many people designate a good friend -- who will follow your wishes for care with a lesser likelihood of being so emotionally involved as to find it difficult to do as you have instructed – such as a wrenching decision to discontinue life support. This is one reason why a friend may be a better healthcare representative than a close – and more emotionally involved -- family member such as a spouse, parent, or child.

Once you have decided who to designate as your healthcare representative – and once they have agreed to take on this important role (an alternate representative may also be designated should your primary representative be unavailable or decline to make decisions), it is imperative to have a conversation with them about what your wishes would be in a variety of circumstances. For example, some people may want more aggressive care should they become ill with a life-threatening though potentially curable illness than they would if they had a terminal illness with few treatment options and a lesser likelihood of recovery. However, it is impossible to anticipate all medical eventualities— I have tried— and one advantage of the healthcare representative is that he or she has freer rein to direct care in the spirit of your wishes – regardless of your exact medical circumstance -- than is allowed by a living will or MOLST.

To complete your legally enforceable healthcare representative paperwork, which requires two witnesses but again does not require a lawyer or a Notary Public, download a detailed PDF outlining Advance Directive procedure in Connecticut (including healthcare representative, Conservator of the Person, living will, and anatomic donations. MOLST cannot be completed with an online form – see below).

It is worth noting that you must be able to understand the consequences of your decisions to designate a healthcare representative. People who are significantly cognitively impaired, from dementia, for example, and are unable to direct a healthcare representative sensibly and reasonably, are not eligible. Likewise, someone with impaired consciousness is also not eligible. This is why it is important to choose one before becoming seriously ill.

For the sake of completeness, if you designated a durable power of attorney for healthcare in Connecticut before October 1, 2006, that person has the same medical decision-making rights as a healthcare representative. If you designated a healthcare agent – not a representative -- prior to October 1, 2006, that person may only make decisions about withdrawing or withholding life support, not all healthcare decisions. And if you don’t have a legal Advance Directive in Connecticut, healthcare providers will look to your next of kin for decisions. In order of preference, these are your spouse, adult child, and parent -- or other relatives if they are not available.

All in all, and especially considering the difficulty healthcare providers will have following instructions if family members disagree about the care you should receive, these factors make it clear that it makes far more sense to simply designate an up-to-date healthcare representative and to do it now.

A Connecticut “Conservator of the Person” is an individual, often a lawyer, appointed by a Probate Court and responsible for healthcare decisions for someone who is permanently unable to care for, and communicate their healthcare decisions – such as someone with dementia. Usually, Conservators are assigned to people who have not designated a healthcare representative and are no longer capable of doing so. While a Conservator is empowered to make all healthcare decisions, their role usually relates to custodial needs— such as admission to a nursing home— although they may also make decisions about specific medical interventions. If someone with a court-appointed conservator already has healthcare representative, having designated one while they were still able, the decisions of the healthcare representative about day-to-day medical care have more authority than those of the Conservator, unless the Probate Court disagrees.

These instructions require no further input from you, a healthcare representative, a Conservator, or anyone else to be followed by healthcare providers. The Connecticut Living Will provides instructions about your wishes regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation—or CPR — mechanical ventilation (such as a respirator), artificial nutrition and hydration, (such as tube feeding), and any other specific medical requests you may choose (such as intravenous antibiotics). The Living Will, however, is very specific as to the medical circumstances in which healthcare providers can follow its directives. These include suffering from a terminal illness, permanent unconsciousness, permanent coma, or persistent vegetative state. One potential problem with the Living Will is that reasonable people may disagree on the definition of these entities. One medical provider may believe a condition is terminal, while another may feel that there are still medical treatment options. Likewise, there may be disagreement as to whether a state of unconsciousness or coma is permanent, and how exactly to define “persistent vegetative state.” Recent research in people believed to have no conscious awareness of their surroundings— part of the definition of persistent vegetative state— has shown that some patients may have more awareness than others. This may complicate matters should there be disagreement as to whether you are in persistent vegetative state. I have seen more than one situation in which it was clear that a grievously ill patient would have wanted to be taken off life support but the wording of their living will tied the hands of their healthcare providers. A healthcare representative, on the other hand, can make decisions regardless of these uncertainties, although they should not stray too broadly from your expressed wishes. For example, someone might instruct their healthcare representative to decline further medical interventions – or to stop life support -- should the likelihood of their being indefinitely and seriously neurologically impaired be high, regardless of whether they are terminally ill, “permanently” unconscious, or suffering what may or may not be persistent vegetative state. This decision is up to each individual, and is important to convey to a healthcare representative.

Technically, MOLST is not an Advanced Directive because it specifies the medical treatment that is desired at the time the form is complete, not at some imaginary future time under some unknown medical circumstance. MOLST requires the presence of an “end stage, serious, life limiting illness” or an “advanced chronic progressive frailty condition,” is usually completed by people at significant risk of hospitalization with the risk of death in the very near future, and is very specific as to desired interventions, such as different kinds of ventilator support, ICU care, IV fluid and nutrition, and others. MOLST requires the signature of and counseling by a MOLST trained and certified physician, advanced practice registered nurse (APRN), or physician assistant, and the original lime-green form must be presented for it to be valid. More information about MOLST.

Again, a valid MOLST requires you be counseled by a trained and certified MD, DO, APRN, or PA, and have a signed, original lime green MOLST form. Counseling is imperative -- I have more than once seen incorrectly completed MOLST forms – requesting, for example, both comfort-measures only and life support – unnecessarily complicate care.

The bottom line? At the very minimum, if you are able to read and understand this blog, get to work on designating your legal healthcare representative right now.

Our 52-bed inpatient facility on the waterfront in Branford is perhaps the most distinctive feature of The Connecticut Hospice, Inc. This facility affords gorgeous views of Branford Harbor and Long Island Sound, giving our patients and their families access to an outdoor space without compare - barbeques and picnics around patients’ beds with multiple family members and friends in attendance are a common summer sight (once, a patient’s horse even came to visit).

Our inpatient hospice facility also provides the kind of up-to-date symptom management techniques that typically cannot be provided in the home setting. This includes injected pain medications, IV fluids, and other “hospital-like” procedures provided to improve quality-of-life in people with terminal and life-threatening illness. (Note - such interventions are not provided to prolong life. For example, we would not provide IV fluid to an unconscious patient who is very close to the death.)

“Having to tell people they are not eligible is the worst part of my job, and I dread it.”

- Joseph Sacco - Chief Medical Officer at The Connecticut Hospice, Inc

Unsurprisingly, the lovely setting and excellent care make admission to Branford a common request, both for hospitalized people who have decided to enroll in hospice and for those in our home care program seeking a higher level of care. It is a request we wish we could grant for all – but can’t. Hopefully, this post will clarify who is and is not eligible for inpatient hospice care and help avoid disappointment among people who thought it was open to all.

This is the level of care provided for hospice patients who are at home or in a nursing home.

Respite-level care includes five days of admission to our Branford facility (many hospice organizations provide respite care in nursing homes) where care will be provided by our nurses and other staff, allowing family members to rest (some go on a quick 5-day vacation or attend to tasks they’ve had to neglect to care for their loved one).

This is 24/7 care at a patient’s bedside at home, usually provided by a nursing aide. It is only provided for a limited time – generally two days at most – at the very end of life, for patients needing intensive symptom management. Not every patient is eligible, and staff may not be available for an entire 24-hour period.

(General inpatient care, or “GIP”): Hospital-based care, with 24/7 availability of skilled nursing, 7-day/week daytime availability of an MD, DO, APRN, or PA, and 24/7 medical oversight.

Before getting into the details of eligibility for inpatient care, however, let us first make clear that these criteria are a requirement of Medicare, not of The Connecticut Hospice, Inc., and are imposed on all hospice organizations across the country. We truly wish we could provide inpatient care for all of our patients without limitation. Facing serious and terminal illness would seem qualification enough to receive the excellent care offered not only at home but in our lovely waterfront Branford hospital; unfortunately, Medicare does not agree.

The easiest way to determine whether your loved one might be eligible for inpatient care is to ask this question: Must my loved one be cared for in a hospital setting, where skilled nursing care and medical oversight is available 24/7? Or can their care feasibly be managed at home?

Remember that even people who are unconscious but restless, agitated, grimacing, crying out or showing other signs of distress can often be provided successful symptom relief with highly concentrated oral formulations of medications such as morphine or lorazepam put under the tongue, or “transdermal” medications in patch form, such as fentanyl, that do not have to be swallowed to be effective. If these medications have been tried – and Medicare often audits our records for proof that they have – and the only means of providing relief is by injected medications, this would reasonably be considered care that is not feasible at home, and inpatient care would be appropriate.

Wounds that are large and deep, those involving bone or with excessive slough (dead, discolored tissue) or that are obviously infected (I see no need to be graphic, most people are able to tell if a wound is badly infected) may be eligible for inpatient care. There is a caveat, though; wound care in the inpatient setting is not indefinite, and most wounds in hospice care patients do not improve. Once a wound care plan is in place and shown to be adequate to a patient’s needs, we will generally discharge our patient to a lesser setting, where the care will continue to be provided by our home care team in collaboration with family members, or in a nursing home.

“Delirium” is a medical condition characterized by waxing and waning level of consciousness – your loved one may be asleep one moment and climbing out of bed the next -- confusion, short term memory loss, and agitation/restlessness resulting from altered body chemistry in serious illness. It is often seen as people approach the end of life. As with other symptoms, it can sometimes be controlled with oral or under-the-tongue (“sublingual”) medicines. As with other symptoms, Medicare requires that a good faith effort be made to manage delirium at home – if this does not succeed, inpatient care may be an option.

“Sundown syndrome” is characterized by agitation, confusion, and restlessness in elders with dementia that begins when the sun goes down and it gets dark outside. Managing sundown syndrome is hit or miss – medications given at home that work for one elder (such as a sedative like lorazepam – which can sometimes cause a paradoxical increase in agitation -- or an antipsychotic medication like haloperidol or quetiapine) may not help with another. As with delirium, sundown syndrome that cannot be managed at home may be a reason for inpatient admission.

It is understandable that family members of a very sick loved one who have been providing care 24/7 become exhausted and need a break. Unfortunately, this does not qualify their loved one for inpatient admission. The good news, however, is that they will likely be eligible for respite level of care. Generally speaking, patients receiving respite care are relatively stable – which is not to say they do not have a serious illness – take their usual meds, are able to eat, do not need injected medications, and are discharged home after 5 days

It is understandable that family members of a very sick loved one who have been providing care 24/7 become exhausted and need a break. Unfortunately, this does not qualify their loved one for inpatient admission. The good news, however, is that they will likely be eligible for respite care.

Generally speaking, patients receiving respite care are relatively stable – which is not to say they do not have a serious illness – take their usual meds, are able to eat, do not need injected medications, and are discharged home after 5 days

You may be shocked to learn that imminent death – death expected in hours or days – is not a qualification for inpatient admission, most people are. Medicare insists, however, that the criteria outlined above must be met – for example, symptoms of pain or shortness of breath require injected medications for relief – to admit a patient who is at the very end of life. Most patients in hospice die at home. The good news is that our home care nurses are available 24/7 to help families caring for dying patients at home.

You may also find A Compliance Guide to Inpatient Hospice Care provided by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) to be helpful.

You have just been diagnosed with a serious illness and your doctor is doing their best to provide you the information you need to proceed with treatment. You are terrified, overwhelmed and have no idea how to proceed. You feel like you are living out a nightmare.

Robin Kanarek was in the same situation with her husband, Joe, when their ten-year-old son, David, was diagnosed with leukemia in 1995. Robin, though, was an R.N. with over fifteen years of nursing care experience and had the medical connections and background to navigate her son's care. But as David was ready to start high school at the age of fourteen, he relapsed, and it was discovered that his leukemia was more aggressive than his original diagnosis. As he was too weak for another two-year round of chemotherapy, the Kanareks could not find a perfect match for a bone marrow transplant for David; his only chance for survival was a stem cell transplant using his then ten-year-old sister, Sarah as a donor.

Robin and her family navigated two top health centers caring for David for almost five years. David's journey ended in despair when he died in 2000 following devastating complications from his transplant. He was fifteen years old, but their journey continued; and in the midst of their profound grief, the Kanareks attempted to make sense of what had happened to heal and keep their family intact. Their grief was so insurmountable that the Kanareks decided they needed to move abroad to heal privately and focus on helping their daughter adjust to the loss of her beloved brother, become an only child, and living in a new country, and making new friends.

It was in London that Robin started her journey to heal and give her family's life some semblance of normalcy. Two years of intense grief counseling helped her realize that she could share what she had learned from her devastating experience with her son's illness. Soon she began volunteering and fundraising for a U.K. organization that cared for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Robin realized that little attention had been given to the psychological, social or spiritual aspects of care for David or themselves. She soon learned about a subspecialty in 2006—palliative care.

Most people, including health care providers, are unaware of palliative care's many benefits. Many equate palliative care with hospice, but it is not. Palliative care can be introduced at any time of a serious diagnosis and in conjunction with curative treatment, which hospice does not provide. Palliative care is ideally provided by an interdisciplinary team that includes physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, pharmacists, and allied health providers working together to address pain management, education, and medical, emotional, spiritual, and psychological support. Improving the quality of life for those who suffer from a serious or life-threatening illness is the key tenet of palliative care.

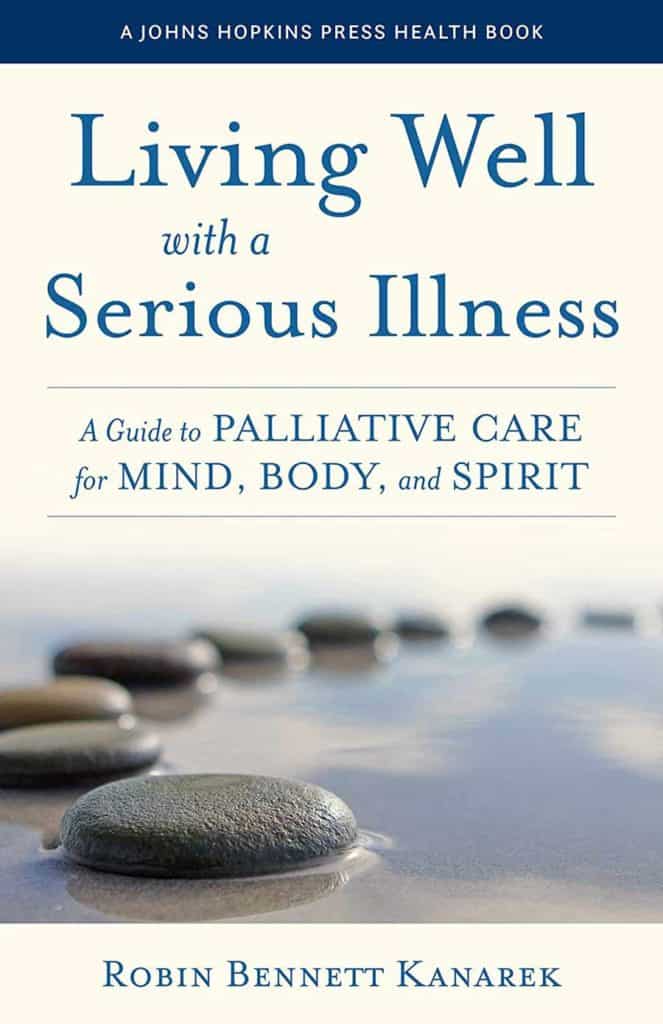

In an effort to help other families with the unique and challenging needs of cancer treatment, Robin wrote her first book, Living Well with a Serious Illness: A Guide to Palliative Care for Mind, Body, and Spirit. The topic of this book is timely. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of individuals over 65 has surpassed those under the age of five. Never before have there been so many people over the age of fifty, the age when, statistically, the greatest incidence of serious and life-threatening diagnoses begins. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), six in ten adults in the U.S. have a chronic disease (four in ten adults have two chronic diseases). These numbers point to a growing need for palliative care, particularly as modern medicine offers more aggressive treatment options for the seriously ill.

The public needs to be educated on the benefits of palliative care. Healthcare providers also require clarification on what palliative care encompasses. Unfortunately, there has been very little written in easy-to-understand language to educate the average consumer; most books on palliative care are textbooks geared toward healthcare professionals. There is a national conversation about recognizing the limits of current medicine and the importance of seeing "patients" as individuals who need and benefit from the care of mind, body, and spirit. That philosophy is the essence of palliative care.

Robin Bennett Kanarek, RN, is the president of the Kanarek Family Foundation, established in 2006, whose mission is to improve the quality of life for those affected by serious, life-threatening conditions through promoting, integrating, and educating the medical industry and the public about palliative and supportive care in all areas of health care. She lives in Greenwich, Connecticut. Her first book, Living Well with a Serious Illness: A Guide to Palliative Care for Mind, Body, and Spirit, is published by Johns Hopkins University Press. It can be purchased on Amazon.

Ms. Kanarek has performed a great service for all of us in the palliative care field. She has managed to write a book that explains, in layman's terms, what everyone should understand about the uses and benefits of palliative care. Even medical professionals will benefit from her discussions of how patients, their families, and their caregivers should be interacting when someone has a serious illness. This book should be on every bookshelf, to be read and reread as the need arises.

―Barbara Pearce, President and CEO, The Connecticut Hospice, Branford, CT

This book is a gift to both clinicians and patients. Robin shared her story from the perspective of a healthcare giver, a wife, and a mother. She speaks to the heart of how the patient and entire family is affected in the face of serious illness. The gift is in the sharing and learning we can all do to ensure David and the Kanarek family's gift of their most private and painful moments will contribute to our better journey.

―Diane P. Kelly, President, Greenwich Hospital; EVP, Yale New Haven Health

This book is essential reading for anyone who will live with a serious illness or care for someone with one―which is essentially everyone. Kanarek writes as a mother who shares the loss of her son and has spent three decades sharing her experience with others to support their journeys. It is a book written from the heart and is both a practical guide as well as a deep reflection of how to navigate the challenging, and sacred, time of the end of life.

―Betty Ferrell, PhD, FAAN, FPCN, CHPN, Professor, City of Hope Medical Center, Duarte, CA

Robin Kanarek is the ideal translator of palliative care for people living in the real world. She is a nurse and knows our health care system. She cared for her own seriously ill child. If someone you love is sick, this book is your guide to the oasis that is palliative care, often hidden in plain sight, but yours for the asking.

―Diane E. Meier, MD, Center to Advance Palliative Care, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York City

Hospice programs are required to provide social work services as a “Condition of Participation” for the Medicare Hospice benefit, but many families do not realize the extensive components offered.

In fact, it can sometimes be difficult for social workers to get into homes to see families, where home hospice care is being given. Although there can be feelings of wanting to withdraw from outside interventions or visits, more often it is because people do not fully grasp the wide breadth of what hospice social work offers.

The first standard of hospice social work is to do what is called an initial assessment. It provides an early glimpse of where the patient and his or her loved ones are, in terms of their understanding of the illness and its progression, preparation for decisions that may need to be made, and where they are in the grief process.

It is not uncommon for families to express their feelings that they have no need for any such help, and to see taking any advice or counsel as somehow being a sign of dysfunction, or an inability to care for their loved one properly.

Social workers go far beyond what that would imply, about being there to fill in where a family cannot cope. Although that can be true, a more useful way to think about their services is to compare them to a compassionate and expert event planner. Death has its own set of rituals, red tape, financial considerations, and especially emotional ramifications. Sitting with someone who does this for a living can not only bring comfort and clarity, but can ease many practical burdens that arise with sometimes overwhelming speed, as health declines.

One important early conversation, with the patient if he/she is able, or otherwise with the family or friends, is about the goals of care.

That last question leads to what is perhaps the most joyous part of a social worker’s job. Maybe there is an upcoming marriage that can be accelerated. Social workers have planned weddings, both for patients and for their children and grandchildren, sometimes even in our inpatient facility or on its waterfront grounds. One family wanted a Disney-themed wedding, to commemorate a family trip, and the social work staff decorated the room, while the arts staff brushed up on Disney tunes to play at the bedside. A beaming bride had mouse ears on, to complement her wedding dress.

Other ceremonies have taken place with regularity, such as birthday parties or anniversary celebrations.

One of the most poignant was a graduation, where the professors came in academic garb, to present the patient with her recently earned diploma. In all of these cases, the social work staff works with the family to achieve those goals.

Goodbyes of all kinds also fall into hospice social workers' purview. Dealing with children’s grief, and the preferences of the patient and other relatives can be a difficult, but rewarding task. There may be times when patients need transportation by ambulance, in order to say those farewells to a person or place, and social workers can make that happen. When the hospice care is not in the home, there can be arrangements made for pets to be present. Even a horse came to our backyard, so that its owner could see it one last time.

Last wishes can range from a favorite food to a video to leave behind, from putting toes in the ocean at the end of life to finishing a last book or article. Whatever closure means becomes the social worker’s goal to facilitate.

Planning a memorial service or funeral falls into the category of last wishes, as well as deciding about DNR/DNI or treatment choices. Even broaching those subjects with family members can be something in which the social worker participates, especially when some relatives have not understood or accepted the disease trajectory.

Financial considerations, including Title XIX applications, can be explained by social workers. They also do discharge planning when people can no longer live independently, and can help to narrow the options and help with the choice of a nursing home, should that be necessary. They are charged with making sure that the patient is safe in whatever environment is chosen.

When there are no relatives, a social worker can even take over some of the role that a family member would otherwise play. They can reach out to people that the patient wants to see, help with household tasks, or just keep someone company. One often-made comment about the end of life is that the days may be short, but the minutes and hours can be long. Having someone objective with whom to talk can be so important.

By now it is clear that social workers fill a vital role in many aspects of hospice care, no matter the setting of that care. They are special people, and they bring a combination of practicality and compassion that is so necessary for both patients and families. Whether they are serving as coordinators or counselors, they can play a part in every patient’s journey. Developing a relationship with them early in the process can make a difference all along the way. If there is a question of any kind, and the social worker doesn’t know the answer, he or she probably knows how to help get that answer.

Most of us know social workers in some setting, because they are so versatile in their career choices. What they do varies tremendously by location, so a school social worker or a prison social worker may do very diverse jobs. It is hard to imagine, however, that anyone could have a position that is more fluid that that of a hospice social worker. They are truly indispensable.

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.