Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

Having seen tens of thousands of patients over the past five decades, The Connecticut Hospice has the highest amount of professional skills for end-of-life care management. Over time, The Connecticut Hospice has progressed from its original beginnings—providing care for cancer patients and their families—into serving all patients, regardless of diagnosis. One of the conditions which has seen a huge increase in incidence is dementia, in part because other diseases can be cured or controlled, leaving more people to suffer from mental decline at the end of life. This can be particularly hard on families, who are often grieving the loss of the person they knew, while that loved one is still alive. Our new program, Magnolia Care, will increase the services and support to patients and families with Alzheimer’s disease, and other cognitive failures.

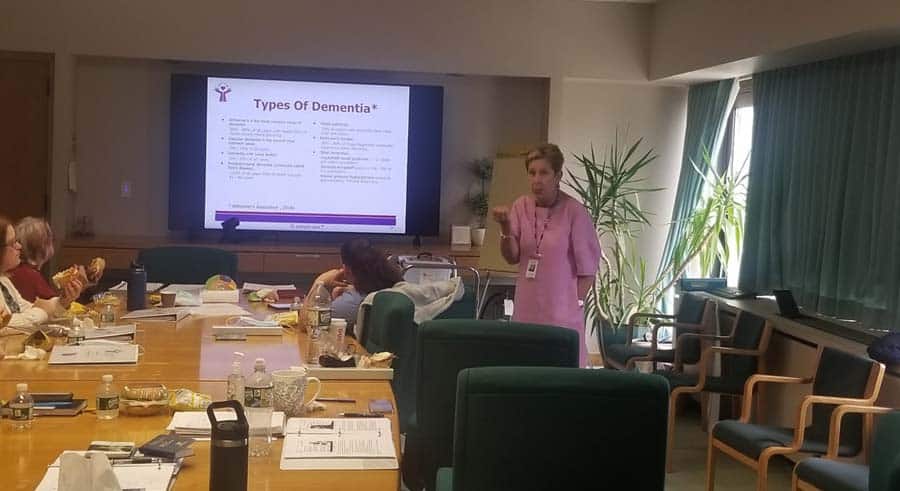

The training that we are giving to our nurses, aides, and social workers, combined with our longstanding knowledge of treatment options that preserve quality of life, has allowed us to design Magnolia Care in the most thoughtful of ways. In order to best understand what we are offering, it will help to provide some explanation of the progression of dementia.

Between 5 and 8% of the U.S. population over 65 is living with some form of dementia, with that number rising to 50% of those over 85. Dementia is defined as cognitive changes that affect thinking, personality, and behavior. It can be difficult to diagnose in its earlier stages and can be confused with other causes of those same symptoms. However, it occurs broadly across these age groups and is expected to increase as life expectancy rises and more people enter this demographic.

Early phases of the disease can often be managed by families without outside support. Minor adjustments in daily living arrangements, or additive monitoring of complex tasks, can suffice for some period of time. Independent living may be a challenge but is sometimes prolonged with enough support from relatives or paid caregivers.

The final stage of most diseases of dementia occurs between 3 and 6 years after a diagnosis is made. The progression of the disease does not follow a specific timeline and is different in each case.

This period of advanced symptoms may be months or years in length and could include a variable course of events which is unpredictable. Regardless of the type of dementia, there are some typical features that are often common at this time:

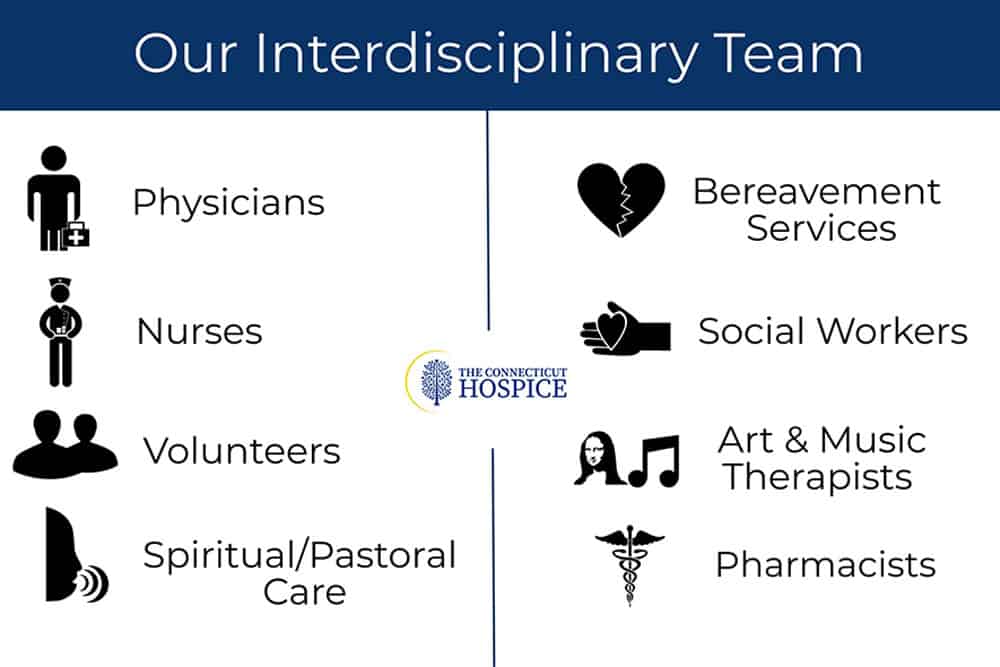

Magnolia Care is designed specifically for persons living with dementia at the end of life. Nurses, social workers, chaplains, nurse aides, art and music therapists, and volunteers all undergo intensive training and are certified in person-centered dementia care and non-pharmacological interventions.

Our final-stage dementia care training was created by a hospice nurse with extensive experience caring for patients with dementia. This dementia-expert-lead training focuses on the behaviors and needs of hospice patients with cognitive failure, ensuring that Connecticut Hospice caregivers can recognize and respond to the concerns of dementia patients and families.

Like all of our Hospice Care programs, Magnolia Care provides a comprehensive approach that incorporates all the members of the hospice team in a plan of care that addresses the unique needs of each patient.

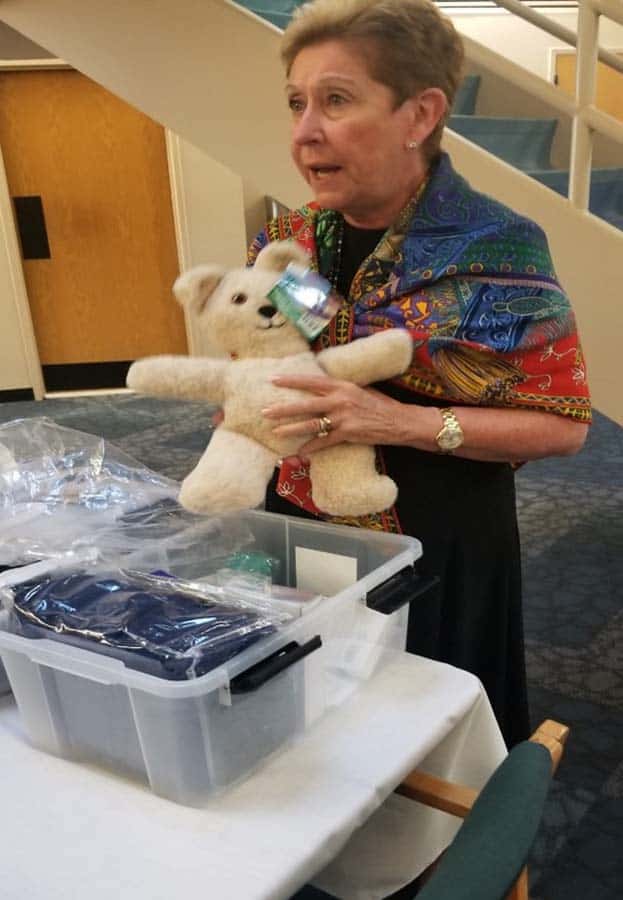

We have assembled a “tool kit” for use in homes, nursing homes, or assisted living, which offers enhanced tools for the management of symptoms, and can allow patients to access deeper memories, providing both solace and joy. The goals are to reach those patients where they are in their journey, help families to communicate and comfort their loved ones, and reduce the need for pharmacological solutions to common problems with behaviors.

Music is a known soother of dementia symptoms, and we work with caregivers to provide appropriate and significant music, tailored to the individual’s taste and age. MP3 players are embedded with this music in teddy bears, comfortably used by even people who are cognitively impaired.

The toolkits also include a diverse range of items to help dementia patients and their caregivers, including:

These dementia care toolkits can be used by relatives, other caregivers, or those on the staff of busy skilled nursing facilities. These resources are packaged in a container made to fit by a bed or chair and is easily stored.

Finding a way to help those around the patient interact naturally and normally is critical in allowing the patient to retain function and, most importantly, dignity. Our staff’s training enhances skills required to meet the pressing physical and emotional needs of hospice dementia patients.

There is much more that can be written or read about cognitive decline at the end of life, but our goal here is merely to introduce some new concepts in dementia care, and to urge you to contact us if you or someone you love might benefit from Magnolia Care. It’s all part of what makes The Connecticut Hospice such a vital resource to both those we serve, and to the field as a whole.

As we close in on our fiftieth anniversary, we are trying, more than ever, to educate, serve, and advocate for those suffering from life-limiting illness. This is our latest milestone. We at The Connecticut Hospice are here to help.

In many parts of the country, people think of hospice care as home care, where nurses come into private homes and help caregivers take care of end of life patients. In our area, Connecticut Hospice’s large inpatient facility brings GIP (general inpatient) to families as well. But hospice care is not just provided in hospices, or in homes. It can be delivered in any setting where a patient lives.

When someone moves to a skilled nursing facility(SNF) or assisted living, that becomes the patient’s home, and home hospice can assist there. For nursing homes, especially, this can be a great boon for families. Especially during the pandemic, much has been written about staffing shortages at SNFs. Hospice nurses and aides can supplement the care given by a skilled nursing facility.

For example, eating can become an issue for people with certain conditions. Sometimes, carefully feeding by trained professionals can increase their caloric intake significantly. Very few places would have the ability to feed many patients that way, but home hospice care can bridge the gap. Often, aide service is requested during mealtimes, and supplements the resources available for meal assistance.

Personal care is another function of daily living that can become problematic, especially with dementia. Patients can become resistant to bathing, or may need time-consuming help with dental maintenance. Again, home hospice aides may be used to add extra resources for those aspects of ongoing support.

At Connecticut Hospice, we have trained all of our home care staff in special techniques to improve the quality of life for patients with dementia. There are methods for feeding, bathing, and other activities that will improve the outcomes for those who can receive such personal attention.

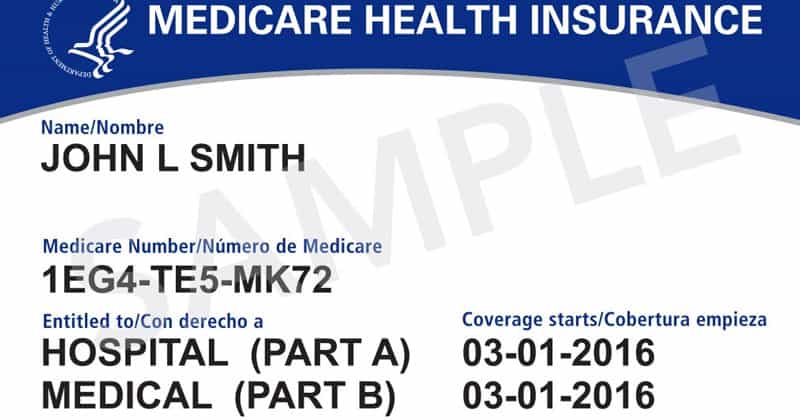

If a patient is accepted as appropriate for home hospice care, he or she becomes eligible for Medicare Hospice Benefits (MHB). Those benefits are specified by Medicare, which pays for most of the hospice care delivered across the country. There are certain parameters for entry into that service, and someone must be referred by a physician. At that point, he or she would be evaluated by a hospice service, and, if appropriate, can then be admitted for MHB.

This can take place in any setting. A patient residing in a skilled nursing facility would be visited there by a hospice representative, and then enrolled in that setting.

Or, a patient can be released from an inpatient hospital or hospice setting, and sent home or to a SNF or Assisted Living Facility (ALF) with home hospice care. Evaluation can take place before the patient is discharged, so that all necessary equipment and medications can be delivered before the patient gets to the next setting.

Home hospice care covers the cost of those medications, as well as the equipment needed. Routine home care does not provide that level of assistance. Sometimes, patients and families resist the use of hospice care, just because of the word “hospice”. Before declining such help, people should understand that Medicare Hospice Benefits are a component of Medicare, and that the financial implications can be great, depending upon the level of care authorized for a recipient.

Accepting hospice home care does not put a time limit on someone’s life, but it does mean that the normal trajectory of an illness would indicate an expected lifespan of less than six months, in the opinion of a referring physician. It also means that they are no longer seeking curative treatment for an illness. We call this “comfort care”, as opposed to active methods of fighting the disease. There is a great range of outcomes with this type of care, but many people live longer. If you need help deciding about when’s the right time for hospice care, we have a list of ready signals that you can discuss with your physician.

Since curative treatment can be debilitating, hospital stays generally take a toll on the patient. Careful management of symptoms, especially pain, is a hallmark of hospice care, and one that can lead to a better quality of life. That in and of itself can prolong a person’s “good” time, and improve his or her outlook. It does not, therefore, necessarily indicate defeat, or failure, to choose hospice care. There are many good reasons to consider comfort care in a safe and supportive setting.

Understanding the finances behind Medicare Hospice Benefits is also key to peace of mind. In a nursing home setting, the family either pays for room and board, or is covered by insurance or Medicaid, depending upon the level of assets a patient has. The extra care provided by a hospice is paid for by Medicare, directly to the hospice.

Even in assisted living, where usually an upfront cost has been paid by a patient, in order to cover whatever services are necessary, hospice care is covered by Medicare, if the person is referred and deemed appropriate. The rules about visitation and distribution of medications can be different, but the concept is the same. Again, the hospice is paid directly by the Center for Medicare Services, as it would be in a private home.

It’s worth a word at this point about virtual hospice in a hospital. If a family member is too ill to transfer to home or even an inpatient hospice setting, end of life services can be provided in a traditional hospice environment. In those cases, the referring hospital would call in a hospice, and it would admit the patient and provide services in the hospital bed.

The hospice pays room and board in those cases to the hospital, but the patient and his or her family is not involved in that process, nor is the family responsible for paying for the extra services of hospice personnel. Not all hospitals have such an arrangement with individual hospices, but it is worth asking to see whether that is an option in any particular case.

For those patients on private insurance, they are also generally available, and the hospice can check for authorization. Also important to remember is that those services can be additive, so that they supplement whatever care is being given already, and provide additional comfort and aid to caregivers.

One of the goals of comfort care is to ensure that patients receive adequate pain relief and symptom support. This alone can lengthen and/or improve life. Another consideration is the reduction of hospital time—if hospice care prevents additional hospitalizations, or reduces the length of stay, it’s understandable why Medicare would pay for it. Caregivers are taught to call hospice before dialing 911, because sometimes episodes can be managed without a trip to the emergency room.

There are resources available to assist patients and families along the journey of an illness, and they are both easily accessible and affordable. As the country’s first hospice, we know well the need for our services, and hope to help others access them whenever appropriate.

Learn more about hospice care, and its many settings.

The Hospice Plan of Care (POC) maps out the needs and services supplied to hospice patients and their caregivers.

If one wanted to probe the essence of the hospice philosophy, it would probably come down to the hospice plan of care, developed for each patient on admission, and revisited every two weeks after that, by the interdisciplinary team managing that individual patient. This plan is mandated under Medicare for hospice reimbursement and has very specific requirements that all hospices must follow. It isn’t just that various disciplines are included in the plan, but that all the practitioners convene to contribute to it. The Connecticut Hospice is very familiar with all these components, since our Founder, Florence Wald, wrote extensively about the various aspects needed for proper patient treatment, as she worked to bring the first hospice care to America almost fifty years ago.

At the heart of what Florence Wald believed was the notion that patients have rights, and should be treated as partners in the care that they receive. She thought, and it was novel at that time, that they should be told their diagnoses and prognoses, and that the whole family should be involved in planning and care of the illness. It seems hard to imagine now, but cancer patients were often not told what their disease was, nor were they advised if it was terminal. This was seen as a kindness, but Ms. Wald felt that it impeded a patient’s ability to achieve closure, and to plan for his or her last days, weeks, or months of life. Today this appears obvious, but, at the time, it led to the idea that there should be an informed discussion about options, treatment, and a patient’s wishes.

This Hospice Plan of Care goes far beyond the concept of advanced directives that many people are familiar with from medical practice currently. It is a plan for comprehensive care that includes preferences about pain medication, sedition, home vs. hospital vs. hospice as a location of care, treatment choices, comfort measures desired, and family involvement. It also includes the more expected areas of funeral arrangements and religious practices, as well as financial considerations.

To many patients and families, the end of life can come as a surprise, no matter how often they may have spoken of the possibility. Too often, they can feel as though they have boarded a train that is proceeding quickly, and without their full informed consent in some instances, toward a destination, they may not feel that they have accepted. There can also be a sense that everything is preordained—that the medical profession will be deciding the next steps, based on superior knowledge. This usually leads to further treatment, either because paths forward presented as possibilities are not understood to be optional, curative, or even recommended, or because someone in the group is choosing extended life as the goal for action, no matter the chances or consequences. Without deliberative planning, this runaway train can end up in a place no one consciously intended to go.

How does a hospice plan of care prevent this runaway train of futile, expensive, and often painful curative attempts? First of all, the care plan is patient and family-centered. The aim is to make sure that the patient’s goals of care and treatment wishes are honored. Palliative care is very different from curative treatment, and both are explained. Comfort Measures Only (CMO) is a totally valid decision to make, and can, not infrequently, even lead to a longer life span. Treatment can be enervating, and frequent trips to the ER or lengthy hospital stays can weaken patients further, and lead to other issues.

Pain is another important topic. Not everyone has the same pain tolerance. Even if they did, some will choose to be more sedated than others, depending upon their own wishes for family visits, final projects, or other reasons. This is crucial to decide with the patient, if possible, since family members, or even the medical team, can be upset by signs of suffering, and want to have them alleviated.

Independence and residence are critical to discuss. For some, living at home is vitally important. Others may be afraid to be alone, or feel more comfortable with attendants around, either in the home, or in a skilled nursing facility. Some wish to undergo rehabilitation, to acquire the strength or ability to perform certain skills. Different options can also be right at different points.

When the end of life approaches, there can again be different preferences. Inpatient hospice care is often chosen by those who don’t wish to burden their relatives with personal care, or perhaps feel that their surviving family will be unhappy to have had them die at home. Some caretaker relatives may be increasingly unable to provide the level of support needed as the disease progresses. In other situations, the patient’s strongest wish may be to die at home. When this is true, all parties need to examine all the requirements necessary to achieve that result. For those who have spent a great deal of time in a particular hospital unit, they may wish to remain in a bed there.

Treating unrelated conditions is another consideration. Sometimes, antibiotics are used, even in CMO cases, to make the patient more comfortable. Others may wish to continue medications they have previously been taking. Many find letting go of all restrictions, dietary or otherwise, is a welcome relief. For them, the team dietician may be less important, but some families struggle to keep patient appetites up, and find that consultation valuable.

Social work, arts therapy, and spiritual care members of the Interdisciplinary Team are involved as well, not only for the typical end-of-life financial or funeral planning, but for help with bereavement and grief. The patient will rest more easily if resources are provided to work on those issues. The patient him- or herself may have spiritual questions or concerns. He or she may simply want to talk to a neutral listener, without fear of hurting feelings or causing pain. Working with an arts therapist, either in home care or in the inpatient unit, can be a way of creating new memories, or accessing old ones. Children especially tend to gravitate toward expressing their feelings through art and music. Assessments in these areas are done at the start of care, and reviewed, with action plans updated, on a regular basis.

How does all of this differ from what a patient and/or the family might accomplish alone? It isn’t always different. Some families are familiar with final illnesses, or extended personal care. Some have talked about what end-of-life wishes are, and all agree on one plan from the outset. If an illness has been lengthy, often especially in cases of dementia, decisions have already been made at various points. For others, however, this plan of care is a helpful introduction to all of the issues involved. For them, the caregiving team is very important in allowing them to accept, cope with, and come to terms with the process. Because there are many disciplines represented on the team, it can happen that different parts of the family relate to different styles or outlooks, and everyone can find relief in some regard.

Dr. Joseph Sacco, the Chief Medical Officer at The Connecticut Hospice, is certified in palliative care medicine, which he has been practicing for many years. He finds patient choice to be a true priority in good hospice care. As he explains, “What is left is choice — the right of patients and families to decide what their doctor should do, based on facts delivered clearly and with compassion.” That quote captures so well the philosophy of hospice: that it is the patient and family who are at the center of the constellation and driving the plan of care, and not the medical team. It is important for all parties to recognize that, even when it seems that there are no choices left, there are choices.

The decision as to how the end of life should unfold is a gift that all hospices can provide to their patients and families, and one that should never be taken for granted. It goes all the way back to the beginnings of hospice care, first in London, and then in Connecticut. The aim is to provide comfort and compassion, and allow all the dignity of fulfilling whatever wishes they can, to the best of their—and our—abilities.

A Comprehensive Breakdown of the Clinical Signs for When Hospice Care is Appropriate

Hospice care is a holistic approach to treatment that focuses on the patient and family which addresses the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual needs of the patient and family.

At Connecticut Hospice, we understand that it is a highly personal decision to begin receiving hospice care and we value the choices and goals of each patient and family. We are here to help you make the decision of when it's time for hospice care.

Medicare Hospice Benefit Eligibility

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2021

The patient is unable to be weighed on scales due to bed-bound status. MAC is 18cm to the right upper arm. During the interview with the daughter, who has been caring for the patient over the past year, she said that her mother has lost weight in the past 3 months but unable to state how much. The daughter states that she has been wearing clothing in a size 16 women’s but now she had to get mother new clothing gradually over the past few months due to her clothing “falling off of her”. The patient is now able to wear size 10 women's clothing.

The patient has been eating 4-6 child-size meals per day but has only eaten about 25% of each meal. This consists of 2 slices of bacon, 3 bits of grits for breakfast. She had a 1/3 of an Ensure supplement, then for lunch, she had a few bites of homemade soup and a popsicle.

The patient requires assistance of one for bathing at the sink, dressing his lower body and now uses a walker for all ambulation inside and outside of his room. The patient was completely independent with all ADL’s and driving and working every day until 3 months ago when he was diagnosed.

The Nurses Aide describes the patient is sleeping 8-10 hours at night and then takes a 3-4 hour nap during the day. When the patient is up in the chair for more than an hour, she is frequently dosing off. This is a change from just 2 months ago when the patient was not even sleeping during the night and was having agitation in the evening and sleeping a few hours during the day only

(HIV Disease, Stroke, and Coma require a lower score to qualify)

| % | Ambulation | Activity Level Evidence of Disease | Self Care | Intake | Level of Consciousness | Est. Median Survival in Days (a) | Est. Median Survival in Days (b) | Est. Median Survival in Days (c) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | Full | Normal No Disease | Full | Normal | Full | NA | NA | 108 |

| 90 | Full | Normal Some Disease | Full | Normal | Full | NA | NA | 108 |

| 80 | Full | Normal With Some Effort Some Disease | Full | Normal | Full | NA | NA | 108 |

| 70 | Reduced | Can't do Normal Job or Work Some Disease | Full | Normal or Reduced | Full | 145 | NA | 108 |

| 60 | Reduced | Can't do hobbies or housework Significant Disease | Occasional assistance needed | Normal or Reduced | Full or Confusion | 29 | 4 | 108 |

| 50 | Mainly sit/lie | Can't do any work Extensive Disease | Considerable assistance needed | Normal or Reduced | Full or Confusion | 30 | 11 | 41 |

| 40 | Mainly in bed | Can't do any work Extensive Disease | Mainly assistance needed | Normal or Reduced | Full or Drowsy or Confusion | 18 | 8 | 41 |

| 30 | Bed Bound | Can't do any work Extensive Disease | Total Care | Reduced | Full or Drowsy or Confusion | 8 | 5 | 41 |

| 20 | Bed Bound | Can't do any work Extensive Disease | Total Care | Minimal | Full or Drowsy or Confusion | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| 10 | Bed Bound | Can't do any work Extensive Disease | Total Care | Mouth Care Only | Drowsy or Coma | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| 0 | Death |

| 100 | Normal no complaints; no evidence of disease | |

| Able to carry on normal work; no special care needed | 90 | Able to carry on normal activity; minor signs or symptoms of disease |

|---|---|---|

| 80 | Normal activity with effort; some signs or symptoms of disease; | |

| 70 | Cares for self; unable to carry on normal activity or do active work. | |

| Unable to work; able to live at home and care for most personal needs; varying amount of sassistance needed. | 60 | Requires occasional assistance; but is abke to care for most personal needs. |

| 50 | Requires considerable assistance and frequent medical care. | |

| 40 | Disabled; requires special care an assistance. | |

| 30 | Severely disabled; hospital admission necessary; active supportive treatment necessary. | |

| Unable to care for self; requires equivalent of institutional or hospital care; disease may be progressing rapidly. | 20 | Very Sick; hospital admission necessary; active support treatment necessary. |

| 10 | Moribund; fatal processes progressing rapidly. | |

| 0 | Dead |

When my first daughter was born, a friend noted: “your capacity for grief has greatly and suddenly expanded.” And it had. The friendship, love, pride and the beauty of certain moments – whether or not we notice them in the moment -- are the fruits of our close relationships. As these treasures mount, so does the potential pain we will feel when suddenly that loved one is gone. As for me, I suppose my own capacity for grief has skyrocketed since that day – which also means there are more people (and a dog) in my life with whom I have strong and loving ties.

We observe mourning rituals because they are personally and culturally important and because we need a script to follow when we are in such unfamiliar territory. Those actions – funerals, wakes, shivahs, burials and unveilings -- represent our external, “public” expressions of loss.

We also have an internal experience, called grief. Unlike mourning, grief does not follow a timeline, or have an end date. Grief is often called a journey, and aptly so.

In one sense, we travel through grief as we experience its different stages, including the grief we start to feel even before the loss. Interestingly, the word “hospice” in medieval times referred to a way station for travelers . . . a place providing sanctuary for footsore and weary pilgrims.

Grief also feels like a constant companion – often a quiet one, sometimes disruptive, sometimes a comforting, and wholly unpredictable.

When my sister died I indeed paid the steep price of love. And I experienced grief as both the trip, and the companion. I have noticed the change in how I feel the pain, more a dull ache now than a sharp pain – and I have felt sad, even guilty and almost disloyal about that. That is the trip I am on.

I also have sudden realizations, like understanding that some of my memories were only shared between the two of us, that no one else would understand. Or that our common traits and quirks are now just mine. I think about how she would have handled pandemic times, what we would have decided about coloring our hair, and how we might talk about politics. Or I will stare at her photo and have a little conversation or a laugh. These make up the grief companion I travel with.

During this time of pandemic, the mourning and grief of the bereaved are layered with the tremendous emotional impact of current circumstances. Survivors of one who has died in isolation due to pandemic restrictions, may feel not only profound grief but also trauma from their loved-one’s rapid decline, their inability to comfort them, and not being with them as they died. Trauma is what happens in the brain when an individual experiences something that takes them beyond their normal emotional coping capacity. Experiencing trauma includes symptoms such as anxiety and flashbacks, and it interrupts the normal grief process.

I believe that many bereaved during these past months have, at best, a shaky foundation for moving through their grief. To those who feel unmoored and alone, I offer sincerest hope that they will find stability to start their journey, and happy memories to keep them company along the way.

The Bereavement Program at Connecticut Hospice is a resource for those bereaved who need grief support after the loss of a loved one under our care. It has become quite apparent that the grief that our bereaved are dealing with has been complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The fact is that many friends and family members, who were unable to visit their loved ones at all, due to the visitor restrictions for hospitals, nursing homes and assisted living facilities, had not seen their loved ones for months prior to admission to Connecticut Hospice in Branford. This has become part of the grieving process for many bereaved, unable to comfort their loved ones, or be the advocate at the bedside. The bereaved we are caring for are grieving what feels to be layers of emotion related to the unexpected crisis of the COVID pandemic in addition to the grief related to the death of their loved one. The Connecticut Hospice Bereavement Program continues to navigate this journey with the bereaved, providing comfort and support during a very difficult time, including group meetings. For more information, call Jennifer Stook, Director of Bereavement Services, at 203-315-7544 or visit www.hospice.com/bereavement-program.

Every September, the Connecticut Hospice community of patient families, friends, and caregivers gathers to celebrate and remember loved ones who passed away during the previous twelve months. Connecticut Hospice understands the special importance of this year's event (honoring patients lost 8/1/19 - 7/31/20) as a safe opportunity to gather while also providing closure for families and friends who might not otherwise have had the chance during this challenging year.

Connecticut Hospice is proud to invite you to its first live, virtual event. This event is not just for Ct Hospice families but for all those struggling with loss. Please share this event with anyone you think may benefit. Simply click on link below to bring you to our YouTube channel.

Ceremony of Remembrance Sunday, September 13th at 4 pm via our YouTube channel:

This link will also be available on our website @ www.hospice.com and Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/CTHospice

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/stress-coping/grief-loss.html

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/supersurvivors/201909/the-power-rituals-heal-grief

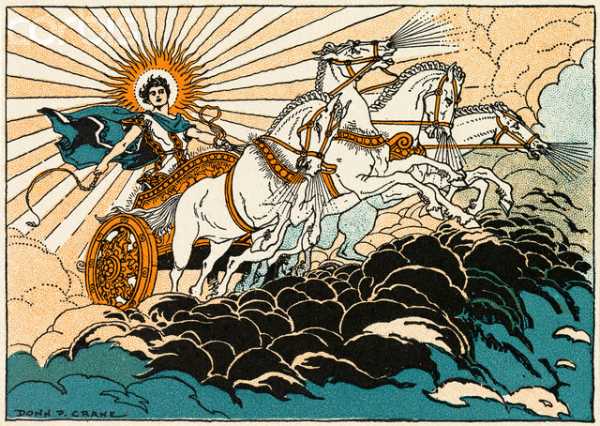

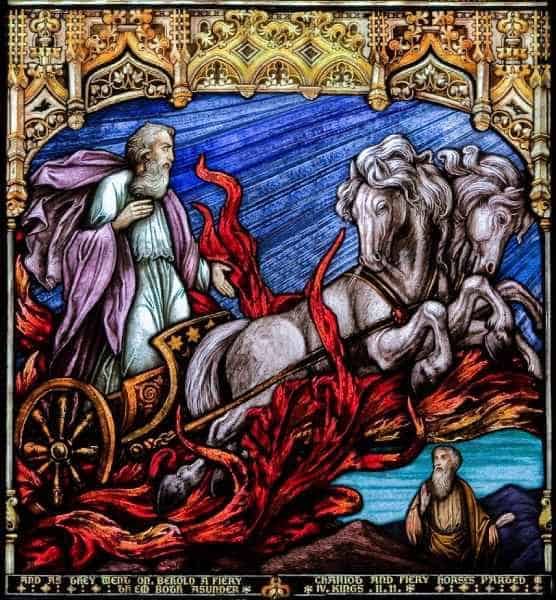

About an hour after my father died, I wandered away from my parents’ den, where he lay in a rented hospital bed, and went outside to be by myself for a while. On the horizon of the cold dusk sky the January sunset was a deep blazing red, more vivid than I remember seeing before or since. I imagined Dad shooting through the sky like a flaming arrow, for he was straight and true. Or like the Greek sun-god Helios arcing across the firmament in his chariot, for he was like the sun to me. Or Old Testament Prophet Elijah spiraling up to heaven in his fiery chariot, for Dad had (briefly) suffered, and deserved this final reward. Or all of these things at once.

These images were felt by me instinctively, and I didn’t share them with my mother, my sister or my daughter - partly because they were so intense I didn’t feel I could speak them aloud, and partly because a little internal voice said that I might be perceived as being melodramatic or even superstitious. Dad was an atheist, besides, and an academic family such as ours generally needed provenance, logic, or science to believe such things, surely?

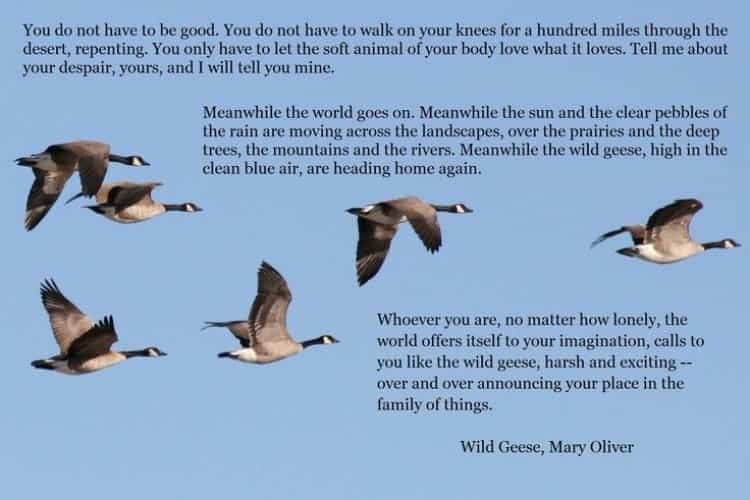

It turned out that we needed none of those things, and a few hours later any doubts I had of such ideas were firmly swept away. Sitting in the dark on the family porch, I was startled by a lone goose, who flew down unusually close to the house, only honking when right in front of me, and then flapped away. It felt like a visit, and I went inside to tell my family about this “amazing phenomenon” before returning outside to the still night air.

About half an hour later Mum came to join me, and literally as she stepped through the door, a chevron of geese swooped down lower than any ever had before, all honking wildly as they flapped by. This had to be a sign, right? Lo and behold, when my sister came out to look for us another half hour later, yet one more goose suddenly appeared out of nowhere to make its presence known.

We all clung to the belief that this had to mean something, because believing the geese were visiting for a reason, that they might even be Dad saying goodbye, brought us comfort in that bleak “dark night of the soul”.

Since then, half the birds of the northern hemisphere’s skies have become ‘symbols of Dad’, such is our wish to remain connected to him in as many ways as possible. My sister and I have talked about this – she lives thousands of miles away, on another continent, and yet she sees the same ‘signs’.

For me, noble hawks always seem to circle overhead when I need his strength;

bright, persistent cardinals pop up in the nearby hedgerow when I want to chat to him;

mated-for-life swans scud silently by to remind me of his marriage proposal to my mother on the second day they met (married five weeks later, they were soul mates for 60 years);

never-shy catbirds hop right up close and train their beady eye on me in the same piercing way Dad always did;

squabbling blue jays even bring back family silliness, when we were a family together;

ephemeral, iridescent hummingbirds are rare and colorful visitors to my yard, but he was rare and colorful too.

And the seminally symbolic geese always bring me right back to the seismic shift in our world on that evening, when at one moment he was alive with us and in the next he had wrenched himself away.

Accepting and allowing that he was gone, in intensely painful slow motion, was like a long difficult labor, delivering a new reality.

Why do human beings believe that signs and symbols from the natural world represent the presence of, or messages from, our loved ones after they are gone? For instance, many people believe that butterflies are deep and powerful representations of life. Butterflies are often thought to be a symbol of their departed loved ones or of eternal life, perhaps because of their metamorphosis from chrysalis to butterfly. Recently, Dmitri, a Connecticut Hospice staff member’s son, felt it was symbolic to release the 6 new butterflies from his Butterfly Garden on the site where hospice care first began in the United States.

Dragonflies are said to symbolize change and transformation, and are connected to signs from loved ones. Feathers, storms and rainbows are also often imbued with special meaning after a loss.

There are websites devoted to supporting the bereaved through the sharing of personal stories of ‘signs and symbols’ they have experienced. Click here for an example: signs of a deceased loved one

People often tell the recently bereaved to “look for signs – you’ll see them all around”, to reassure and comfort, and because they believe it to be true.

It seems that we try to hold onto someone we dearly miss by creating a physical manifestation where there is no longer a physical presence. That so many of these ‘messengers’ are animate entities of the natural world – animals, birds, insects, sometimes even flowers and trees – appears to bear this out.

It is well documented that nature has the power to bring solace and rejuvenation to us whether or not we are grieving, and it is plausible that we instinctively understand this capacity when we so readily ascribe special meaning to its creatures and its beauties.

Nick Cave writes

“The paradoxical effect of losing a loved one is that their sudden absence can become a feverish comment on that which remains. That which remains rises in time from the dark with a burning physicality — a luminous super-presence — as we acquaint ourselves with this new and different world. In loss things – both animate and inanimate – take on an added intensity and meaning”.

Nowadays, when Mum and I sit on the porch together, we sometimes talk about the ‘Great Creative Force” that connects all things. As an artist and woman of great wisdom, my mother can find symbolism and interconnection everywhere. Where once the anecdotes we heard about ‘signs’ from departed loved ones were possibly feasible, but mostly abstract, ideas, our family now knows and feels the truth of them.

We lost him but now he is everywhere.

Further resources:

To read Nick Cave's entire piece, click here: how to understand the experience of loss

To read an essay on birds and loss, visit: the birds scattering blue

What is the 'dark night of the soul'? To explore its interpretations, click here: the dark night of the soul - understanding amidst the absence of meaning

To hear the exquisitely beautiful "Dark Night of the Soul", Ola Gjeilo's composition for chamber choir, piano and string quartet (approx. 13 minutes), watch: Youtube: Dark Night of the Soul, Ola Gjeilo

Learn about and listen to catbird songs: All About Birds: Gray catbird sounds

All about Helios and how he is different from Apollo: Wikipedia: Helios

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.