Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

“A young lad stands!” exclaimed an individual living with dementia, as they translated the first line of their favorite song, “Tumbalalaika” during a music therapy session. In that moment, one with such limited speech prior to engaging in the music, was able to not only sing along, but translate a lyric from Yiddish to English.

As a budding music therapy student at Berklee College of Music, this became a formative experience for Hannah Righter, now the Director of Arts at Connecticut Hospice. To see firsthand the impact music can have on reconnecting individuals to the present moment – so much so that they are able to engage in ways they could otherwise not due to disease progression – was truly eye-opening.

Since then, there have been numerous studies conducted supporting the global neurological engagement that takes place even while passively listening to music (Toader et al., 2023). When combined with the strong emotional connection many have with music, this results in the ability to use music to bypass damaged areas of the brain. This is paramount for individuals diagnosed with dementia, who, through music, can connect with their loved ones in meaningful ways.

The responses evoked by the music might not always be as grandiose as regaining the ability to translate from one language to another. Sometimes, it may be as seemingly subtle as tapping to the beat or maintaining eye contact. Yet, each of these moments can be just as profound as the next. It’s these interactions that highlight the power of the arts in fostering connection, even when verbal communication becomes more difficult.

The story touched upon above is just one of many that speak to the impact the arts can have on patients receiving hospice and palliative care. At Connecticut Hospice, the integration of the arts is woven into the fabric of their care approach, ensuring that every patient and their loved ones have the opportunity to experience art, music, and other forms of creative expression. Whether it’s actively engaging in music and creating a piece of art or passively listening and watching, the arts can play a key role in fostering connection, comfort, and peace.

Connecticut Hospice can proudly celebrate its legacy as the first hospice founded in America, but its remarkable history extends beyond that. In 1979, they became pioneers in the provision of excellent end-of-life care once yet again by incorporating the arts into their interdisciplinary team approach, establishing one of the first Arts programs in hospice care. Since then, the Arts Program at Connecticut Hospice has only continued to grow, expanding its reach through a diverse team of art and music therapists, volunteers, students, and a highly skilled portrait artist.

With Creative Arts Therapies Week falling in the third week of March, it's the perfect opportunity to recognize the invaluable contributions of Connecticut Hospice’s art and music therapists, who work closely with patients and their families both at their inpatient facility and in the community. Their therapists are dedicated to enhancing quality of life for as long as life is lived. Through the power of art and music, they address goals that extend beyond artistic or musical achievements, focusing on emotional, mental, and spiritual well-being.

Whether it's using patient-preferred music to increase relaxation, collaborating with an art therapist to create a meaningful gift for a loved one, or helping patients express themselves by composing a song with a music therapist, their work promotes connection and healing. Hospice’s art and music therapists work to create a space where individuals can confront, explore, and articulate complex emotions while also finding creative ways to honor and celebrate a life lived. Ultimately, one of the most rewarding aspects of their work is helping provide patients and families with the chance to create lasting, positive memories, even in the most challenging of times.

Discover how the arts bring comfort, connection, and healing to hospice patients. Explore Connecticut Hospice’s Arts Program to see how you can support or get involved.

Opioids are commonly used to relieve pain and shortness of breath in seriously ill people and those at the end of life. While highly effective, these drugs also cause side effects that may limit their use.

Addiction – also called opioid use disorder – is believed by many to inevitably result from prolonged use of opioids, but this concern is unmerited when these important medications are used appropriately by experienced practitioners.

Common opioid side effects such as sedation, constipation, and nausea usually wear off within a few days of use and can be countered with other medications. For example:

Other, less potent but effective pain medications include:

Adjuvant medications are drugs that are not primarily designed for pain relief but can help manage pain by either enhancing the effects of traditional pain medications or providing their own analgesic properties. They are especially useful for neuropathic pain, which often does not respond well to opioids alone.

Adjuvants include medications that either:

Used for:

Used for:

Used for:

Used for:

Used for:

While it is beyond the scope of this blog, all these agents have side effects and toxicities. Anyone using them should:

Pain is often worsened by underlying conditions, such as:

Managing these conditions alongside pain treatment can significantly improve overall well-being.

At Connecticut Hospice, we specialize in expert pain and symptom management for patients facing serious illness and end-of-life care. Our dedicated team understands that effective pain relief is essential to maintaining comfort and dignity.

Whether through outpatient care or our licensed inpatient hospital, we provide the highest level of personalized pain relief and symptom control to enhance quality of life.

Compassionate, expert pain relief is our priority. Let us help you find comfort and dignity at every stage of care.

Call us today at 203-315-7543 to learn more or schedule an appointment.

As we age, our needs evolve. For seniors, these changes may include complex health conditions, mobility issues, or memory impairment, making it harder to manage daily activities. Navigating these challenges can be overwhelming for both seniors and their families. This is where Geriatric Care Management services come into play—offering essential support to help seniors lead healthier, safer, and more fulfilling lives.

What is Geriatric Care Management?

Geriatric Care Management is a specialized service that provides personalized care coordination for older adults. Geriatric Care Managers (GCMs), also known as aging life care professionals, are trained to assess the needs of seniors and create a comprehensive care plan tailored to their unique situations. This service helps families ensure that their loved ones are receiving proper care while improving their quality of life.

Key Services Provided by Geriatric Care Managers

The Benefits of Geriatric Care Management

When to Consider Geriatric Care Management Services

Geriatric Care Management services are beneficial in various situations. Some examples include:

If you notice that your loved one’s health is declining or that daily activities are becoming increasingly difficult to manage, it might be time to consider the support of a Geriatric Care Manager.

In conclusion, Geriatric Care Management is a valuable service that provides older adults with the support they need to age with dignity, comfort, and independence. By partnering with a trained professional, seniors and their families can ensure that the right care is delivered at the right time. Whether it's coordinating medical care, managing emergencies, or simply offering guidance, a geriatric care manager can make all the difference in enhancing the lives of aging adults and their families.

If you're considering Geriatric Care Management services, JDT Care Solutions, a new program under The Connecticut Hospice umbrella of services, offers a free 15-minute professional consult to determine how a geriatric care manager can best support you or a loved one’s unique needs.

Please contact Lorraine Castronova, MSW, LCSW

JDT Care Solutions, Geriatric Care Manager

Email: [email protected]

Office: 203 315 7692

Cell: 203 500 2850

Many people who are considering hospice care ask the question: “Can I continue to see my doctor after I enroll in hospice?” This guide will answer that question, and clarify Medicare’s seemingly complicated rules in hopes of promoting your ongoing involvement with the doctor who has served you so well.

This guide focuses on Medicare, which is the insurer for most people in hospice -- the Medicare Hospice Benefit (MHB). If your hospice care is not covered by the MHB, you may want to contact your insurer directly to find out the rules.

Usually, the doctor that people want to continue to see is the specialist who treated them for the condition that led to hospice enrollment, for example, a cardiologist for people with heart disease or an oncologist for people with cancer.

It is possible for your specialty doctor to remain involved in your care, provided he or she agrees to act as your “hospice primary attending.” This is the doctor who works with the hospice interdisciplinary team (IDT) to guide care – mostly by providing medication orders over the phone to the hospice nurse who comes to your home.

If you want your specialty doctor to remain involved in your care, ask him or her to agree to be your hospice primary attending – but remember that most of his or her involvement will be in directing your care over the phone with your hospice team, not in seeing you in the office. They are also unlikely to order blood tests, x-rays, or CT scans for you, as those tests will not contribute to your comfort after you are no longer being treated medically. (And you may be billed for them if they are ordered.)

You can still see your regular – non-hospice – primary care doctor while you are in hospice, or a specialty doctor that you see for a condition unrelated to hospice. For example, if you are enrolled in hospice for lung cancer but also suffer from rheumatoid arthritis. It is important to understand, however, that the Medicare Hospice Benefit will not pay for primary or specialty care, or medications, for services unrelated to your hospice diagnosis – the condition that led to your enrolling in hospice, like heart disease or cancer. However, Medicare Part B (which pays for office visits) and Medicare Part D (which covers prescription medications) will usually still pay for these services – though you should notify the non-hospice specialist and primary care doctor that you are enrolled in hospice and covered by the MHB before making an appointment.

If you decide not to ask the specialty doctor who provided care for the condition that led to your enrolling in hospice to act as your hospice primary attending, or if he or she chooses not to do so, your hospice care will be assumed by the hospice medical director or another physician employed by or contracted with hospice. For example, if your oncologist declines to be your hospice primary attending, the hospice MD becomes your doctor. If you still decide to see your oncologist, the MHB will not cover the visit, and you may be billed for it.

In summary, your care may continue to be directed by your specialty doctor if he or she agrees to be your hospice primary attending, though that will probably not involve office visits, blood tests, x-rays, or CT scans. If your doctor declines that role, your care will be overseen by a hospice doctor. Doctor visits and medications that are unrelated to your hospice diagnosis are not covered by the Medicare Hospice Benefit, but are generally still covered by Medicare Parts B and D.

Feel free to call the admissions department at The Connecticut Hospice, Inc., at 203-315-7540 if you have questions.

Connecticut Hospice recently held a ribbon-cutting ceremony to celebrate the opening of its Palliative Care Clinic. This celebration occurred shortly after the official launch of its Palliative Care Program, Stand by Me. In addition to meeting with our clinicians at their newly launched waterfront clinic, services can also be provided at skilled nursing homes and long-term care facilities.

The Stand by Me palliative care service is a physician and APRN consultative program for the treatment of discomfort, symptoms, and stress caused by a serious illness. Palliative care works with primary medical practitioners to attain treatment goals, prevent or ease suffering, and improve quality of life. It gives patients a chance to live better, have better physical functioning, and decrease depression and anxiety.

The goal of Palliative Care is to improve the quality of life for patients being treated for serious illness. It is appropriate for all stages of treatment, starting at diagnosis. The focus is on relieving complex physical, psychological, social, and/or spiritual problems related to life-limiting or irreversible illness. It includes counseling on disease management to empower patients to better understand their illness and its treatment so they can choose the care best suited to their unique needs.

Palliative care is available to you at anytime during the course of your illness. You can meet with a palliative specialist as little or more often as needed. Palliative care does not mean you are dying, it is about living better, healthier, and being as comfortable as possible. This all leads to a better quality of life and better engagement with loved ones. Very often, people under palliative care continue treatment of their disease and stabilize and graduate from the service. Palliative care is about living long and well!

Learn more about our Outpatient Palliative Care Services

You should not have to endure unnecessary suffering from symptoms of disease or treatment. We respond promptly to calls for assistance, offering 24/7 support. We understand the urgency of your needs and can swiftly schedule in-person visits with our full-time Advanced Practice Registered Nurse, ensuring expert symptom management and counseling on disease management options within days, not months.

Call today to schedule an appointment: 203-315-7540

Click the links below to learn more about Palliative care vs. Hospice care.

Compassionate Care: Hospice vs. Palliative Care Insights

Palliative Care vs. Hospice Care—What You Need to Know

Mother of a Cancer Patient Authors a Guide to Palliative Care

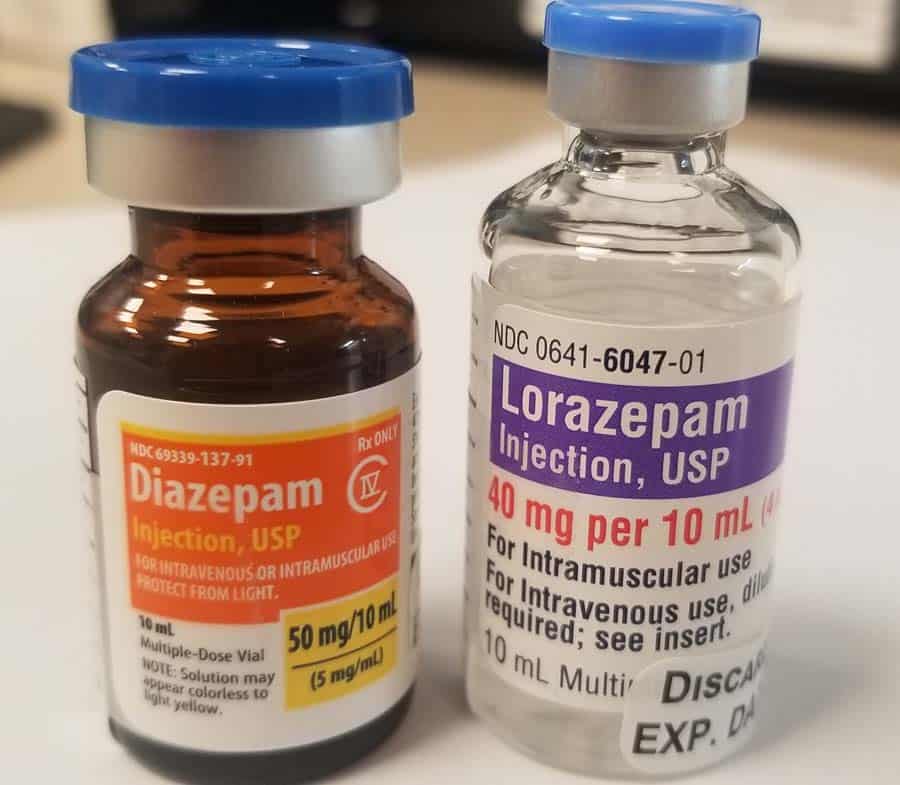

Hospice care is a specialized form of healthcare that focuses on enhancing the quality of life for individuals with terminal illnesses. The goal is to provide comfort, support, and dignity during the end-of-life journey. However, the use of medications, particularly benzodiazepines, have been both a blessing and a controversy in end-of-life care. In this blog post, we will explore the role of benzodiazepines in hospice care, the benefits they offer, potential drawbacks, and the ethical considerations surrounding their use.

Benzodiazepines are a class of sedative drugs that act on the central nervous system. They are commonly prescribed to alleviate symptoms such as anxiety, insomnia, and seizures. These medications produce a calming and sedative effect. Examples of benzodiazepines include diazepam (Valium), lorazepam (Ativan), and alprazolam (Xanax). While these medications can be highly effective in managing certain conditions, their use in hospice care requires careful consideration.

The use of benzodiazepines in hospice care requires thoughtful reflection. Key considerations include:

Palliative sedation is a carefully regulated and monitored medical intervention that is employed when other forms of symptom management have proven ineffective. It is typically reserved for patients experiencing severe distress, refractory symptoms, or existential suffering that cannot be alleviated through conventional means. Palliative sedation aims to balance the relief of symptoms with the preservation of patient comfort and dignity. Benzodiazepines, a class of sedative drugs, are frequently employed in palliative sedation due to their effectiveness in promoting a peaceful and comfortable experience for patients nearing end of life.

The use of benzodiazepines for palliative sedation in hospice care is a complex but widely ethically accepted practice. These medications offer effective symptom control and rapid onset of sedation, and their use requires careful consideration of individual patient needs, open communication, and adherence to ethical practice – long a core principal of patient care at Connecticut Hospice. The goal of hospice physicians who employ palliative sedation is always the enhancement of patient comfort and dignity during the final stages of life. By embracing a patient/family-centered, multidisciplinary approach, healthcare professionals can provide compassionate care that honors the values and preferences of those under their charge, ensuring a peaceful and dignified journey toward the end of life.

The use of benzodiazepines in hospice care requires careful consideration of medical, ethical, and patient-centered factors by experienced physicians and nurses. These medications offer valuable benefits in managing symptoms associated with terminal illnesses; patients and families may be assured that the healthcare providers at Connecticut Hospice expertly navigate all potential concerns associated with their use. Open communication, informed consent, and regular reassessment are key components of a comprehensive approach to benzodiazepine use in hospice care, ensuring that the patient's final journey is characterized by comfort, dignity, and respect for their autonomy.

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.