Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

Many articles have been written recently about the extraordinary life of President Jimmy Carter. He has been praised for having the richest post-presidential life of any former President, although there is certainly a lot of competition (beginning with William Howard Taft, who went on to serve as Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court). No one can deny, however, that Carter has done a great deal for humanity in his “golden” years. He even won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts.

At 98, he has outlived every other former President, and is clearly an outlier in longevity, as in so many other areas of his life. For the past six or seven years, he has been battling metastasized melanoma. With lesions even on his brain, he appears from a distance to have continued to have a somewhat normal life. Now, given his condition and his advanced age, he has chosen to end treatment, and enter hospice care at home.

As he has in other ways, he is teaching us much about how to end a long and full life. Those of us who are in the hospice field hope that he lives for many months, since one of our major challenges remains getting people into hospice care in time to reap its benefits. We hope that he is accessing social work, pastoral care, equipment, and palliative treatment.

It is likely that anyone his age would meet the basic requirements for entering hospice care. All that is necessary is a doctor’s referral, citing at least one condition that, left untreated, could result in death within a six-month period. At 98, who would question that? In addition, providers look to assess the needs of patients by considering whether they have problems with, or require assistance with, ADL (Activities of Daily Living). It seems likely again, given that he is so old, that he would need help with at least some regular tasks.

While palliative care is provided for the relief of symptoms, it has a very different aim than curative treatment. It is intended to make the patient comfortable. Not all nonagenarians have pain, but the majority probably have some arthritis, stiffness, or just aches and pains. They could have trouble swallowing, have a level of memory loss or dementia, or suffer from lasting effects of past medical treatment. Making someone’s remaining time more comfortable is a primary goal for hospice workers.

Jimmy Carter’s deep Christian faith has been well documented. Even he, though, is now going through a new experience. Whether he has concerns for himself, for his 95-year-old wife, Rosalyn, or for other relatives, there may well be issues of closure or unfinished business. Pastoral care professionals and social workers are included on a hospice team, and they begin by assessing risks of bereavement for those who will survive, as well as by determining what support would be useful for the patient him/herself. These staff members also assist with the practical aspects of the dying process-funeral arrangements, paperwork, financial questions, and other issues of concern. Although we can all marvel at the length of his life, that often does not diminish the grief felt by the family, or ensure that all necessary steps have been successfully completed.

If the Carters are fortunate, their hospice will offer arts therapy and support, including home visits. While this is not a condition of participation for Medicare reimbursement to a hospice, it is a wonderful additional service that many of us fundraise to be able to offer. Music can often unlock memories and even speech in patients who have stopped talking, and arts therapists can help all members of a family to express their feelings with concrete objects or drawings. Our hospice even has an artist who provides portraits of the patient, at the request of families. These are often used at memorial services, and can serve as beloved mementos.

We often have spouses, in particular, say that they “breathed a sigh of relief” when the hospice team took over, and they could feel supported and freed from worry. People in the home, when hospice care is given there, are given instruction on the use of “comfort packs”, which are left in case of increased pain or new symptoms that arise between nursing visits, as well as on other equipment and safety procedures. They are also given a number to call, at any time of the day or night, instead of 911, if they have chosen DNR status. Rather than be taken by ambulance to the hospital, they can be talked through issues or questions by a member of the hospice team. After the patient has passed, the family can immediately reach out to hospice, who will come and do the legal death pronouncement, so that the body can be removed. While there is no required timetable for any of this, the family can count on its hospice to be there for them.

We wish for President Carter and his family the peace and joy that can come with a period of reflection, togetherness, and letting go. Hospice staff members often comment that it is a privilege to spend time with those who are dying, and that there is often more joy than sorrow, made more likely by the absence of pain or the effects of treatment. In addition to his years of national and charitable service, we are grateful to him for bringing attention to the benefits of hospice care. He is once again leading by example, and we will all be better for it.

USA Today: Jimmy Carter is in hospice care. Explaining the end-of-life care over 1 million Americans choose.

New York Times: How to Choose a Hospice

New York Times: How Does Hospice Care Work?

Around the country, in all types of health care, there’s a not-so-hidden secret: We, as a society, are not doing our best for those at the end of life. We are starving the palliative, home care, and hospice fields, in order to spend more on acute hospitals, medications, and procedures. The result is that Americans are now living longer than they used to, but have stopped increasing their years of “good quality” living. More and more of them live with pain, disability, chronic conditions, and limitations on daily activities.

It isn’t so hard to figure out how we could improve the situation, but our systems are not set up to assist patients in making decisions about types of care, living situations, and end of life wishes. Although almost everyone questioned in surveys says that they don’t want to die connected to tubes and machines in a hospital bed, that has become increasingly common. Not only is it hard to have discussions about hospice care at the bedside, but it is actually almost always easier to get coverage for an emergency room visit and a hospitalization, than it is to be approved for inpatient hospice care.

Hospital stays and rehab stints drain patients, and they often come out with diminished energy and capacity, yet the next episode turns out to be much the same. In today’s busy health care world, an ED visit can lead to 24 or 48 hours on a gurney in a hallway, never a prescription for optimal treatment. In fact, hospitals have to admit patients after a certain number of hours in the ED, regardless of bed availability or final disposition.

How can we stop this vicious cycle? We need to revisit the purpose and terms of the Medicare Hospice Benefit (MHB), passed by Congress almost exactly 40 years ago, with significant input and involvement of our Connecticut Hospice, the country’s first hospice. At that time, there was no coverage for inpatient stays, and the MHB was viewed as a major step forward. While that’s true, many of the criteria used at the time were randomly chosen, and need to be looked at in light of today’s realities.

Let’s begin with the name. Most of us in the field would like to see another moniker, perhaps the Advanced Illness Benefit. The word “hospice” tends to frighten people, including relatives, and they can delay choosing it until too late in an illness, just for that reason. Advanced Illness would convey that someone might be ready for palliative care and symptom management, instead of curative treatment, but without the finality that hospice implies.

It would also encompass palliative care, which is often left out of the picture entirely. Physicians have long known the benefits of treatments that reduce pain and suffering. Take, for example, radiation for bone cancer. That is prescribed to alleviate pain, not to cure the cancer, and it is a well-established course of treatment. However, palliative care is not always covered by commercial insurance companies, and is compensated minimally by Medicare.

Studies have shown repeatedly that, in many instances, palliative or hospice care can lengthen someone’s life just as much as an operation or chemo, yet is not always offered as a choice, as it is in short supply, plus it is a money loser for every hospice in the country. We can only afford to do so much of it, because our reimbursement does not begin to cover the cost, and is especially not keeping up with the recent rise in nursing salaries.

We should also look again at the six-month limit used in the MHB. While that is not a final upper limit—it just means that, without treatment, the person’s illness is likely to run its course within six months—it does tend to make people wait too long to enter supportive care. While many people are recertified, and do stay in our care for multiple certification periods, the six-month criterion sounds like a true end-stage development, whereas patients who enter supportive care sooner can live fuller, richer lives for far longer than those who do not.

The definition of General Inpatient (GIP) eligibility is neither clear nor consistent. We are allowed to keep patients in an inpatient setting if “care in any other setting is not feasible”. That’s subjective, and overlooks the fact that many patients come to our inpatient unit because they don’t need an acute-care hospital bed, but they are too sick for a skilled nursing facility or a home setting. It would seem that those people would fit into the definition above, but here’s the catch: Our goal is to make them comfortable, by adjusting medications and providing skilled care. However, once they are deemed “comfortable”, they become ineligible to stay, even if they are taking twenty doses of medications in a day. Translated, that means that, once we are doing our job, we are out of a job. Needless to say, that isn’t an easy message to convey to grieving families.

There are other items in the MHB with which we might quibble, such as which therapies, treatments, and medications should be covered, but a complete overhaul is really necessary to address the issues above. If we do not, we are guaranteed to continue spiraling upward in our healthcare costs as a nation. As our population ages, they will need more and more skilled care. If we go on paying for procedures and even experimental treatments, but not for basic symptom management, we will be driving people toward expensive plans of care that won’t work, and that they may not even want.

Forty years is a long time. Just as the boundaries of neonatal potential have grown, so too have our abilities to prolong the other end of life. We don’t always provide the quality of that life along with the treatment. When we do surveys, most of those answering say that they want to die with dignity, with their faculties, and not in pain. Why can’t we all commit to a system which will allow hospitals, hospices, and home care agencies to provide exactly that? We know that it will cost less than what we are doing now, and we know that the end of life can be better for many.

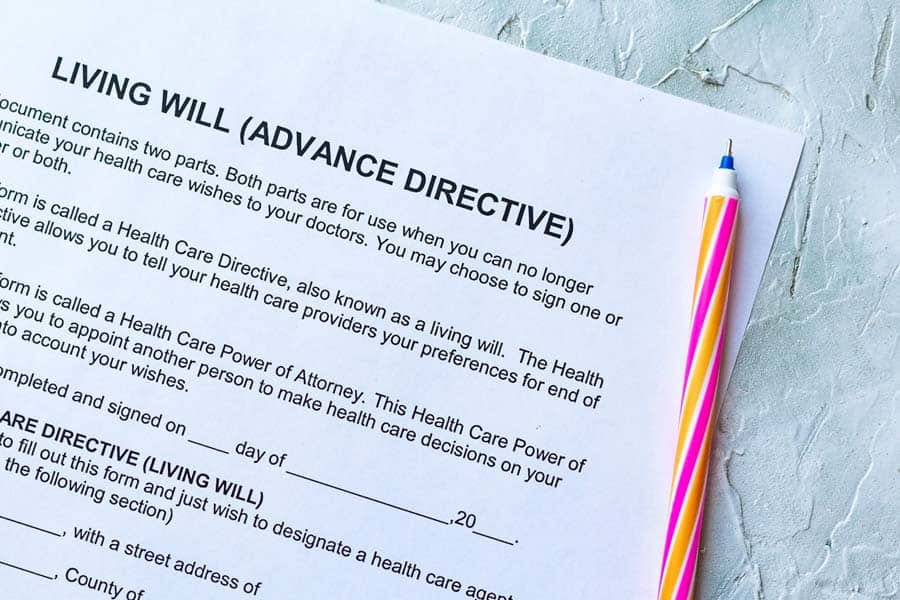

What can you do about this problem? First of all, put your own house in order. Make sure that you have a living will, and a health care agent. Discuss your wishes with your loved ones. Write down anything that you think might be forgotten in an emergency. Carry those documents with you, if you think there might be any need for them, or, better yet, have them entered into your electronic medical record.

However, there is another stage of action, and that involves the national scene. Write or call your Congressperson and Senators, and advocate for a major overhaul of the Medicare Hospice Benefit. All you need to know, in order to find this important, is that half of the Cares Act money during COVID that was meant for hospice care was earmarked for increased fraud investigation in the industry. While every field has some misspent money, the vast majority of end of life providers are trying, with increasing difficulty, to find a way to help our citizens to spend their final days in comfort and peace. We often joke that no one lies to get into a hospice, but the underlying point is clear: We provide a vital service to the most vulnerable among us, and we fulfill a huge need in our society. Please help us help you.

We do a lot of fundraising in the hospice field. One might ask why that is so, since Medicare and Medicaid represent over 90% of our patient accounts. While the amount they reimburse may creep up a little each year, it does not cover all hospice services. Also, Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement does not keep up with the actual cost of what it covers.

For example, most people know that nurses and other healthcare professionals, and paraprofessionals are in very short supply, particularly since the onset of COVID. Their hourly rates have gone up multiple times just in the past year, and most make 25 to 50% more than they did a year ago. Medicare’s single-digit raise in rates won’t be enough to attract and retain the staff necessary to admit and care for patients and families.

Many other costs, affected by the supply chain issues we all face, have also gone up dramatically. Not just the food we serve in the inpatient unit, but the mileage costs for home care providers, the electricity we use, and most other goods and services have increased over the past year. Again, Medicare and Medicaid do not match those raised prices.

Even if we were to be reimbursed enough to provide care, that does not address the needs of the physical plant. Over time, we have had to replace our roof, our HVAC system, our generator, our water tanks, our medical equipment, and our inpatient furniture and fixtures. We could all have sticker shock looking at furniture prices and shipping costs, but that would not pay to buy new bedside chairs, recliners, or privacy curtains.

Mental health issues have risen all over the world in recent years, and hospices are no exception. We need more social workers, who are also in short supply, as well as more pastoral and bereavement counselors, just to meet the needs we see in our population. Their average hourly rates are also rising.

Even in fields where salaries have traditionally been lower—food services, maintenance, and housekeeping—we have a responsibility to offer a living wage, and the competitive necessity to do so. Benefits are a big part of the increases, and we know all too well what has happened to health insurance rates.

Medicare does not cover the arts as a discipline, but hospice patients, families, and the staff all benefit from having those resources on hand. Music and art therapy can help children facing loss, patients with dementia wishing to recover memories, or grieving visitors. We count on donor dollars to pay that overhead, and think it is money well spent.

Just as churches often have a minister’s fund to cover unplanned expenses in times of crisis, we also have a fund to meet those needs. We have paid for cremations, groceries, travel costs, and even some last wishes, and are very glad to be able to do so.

Even we have unanticipated needs: the pipe that backs up and spews oil into the yard; the hurricane cleanup that was not in the budget; or the snowplow that breaks down in winter. We depend on generous donors to help with those emergencies, and a few that are not as critical, but just as appreciated, such as the refurbishment of the prayer room.

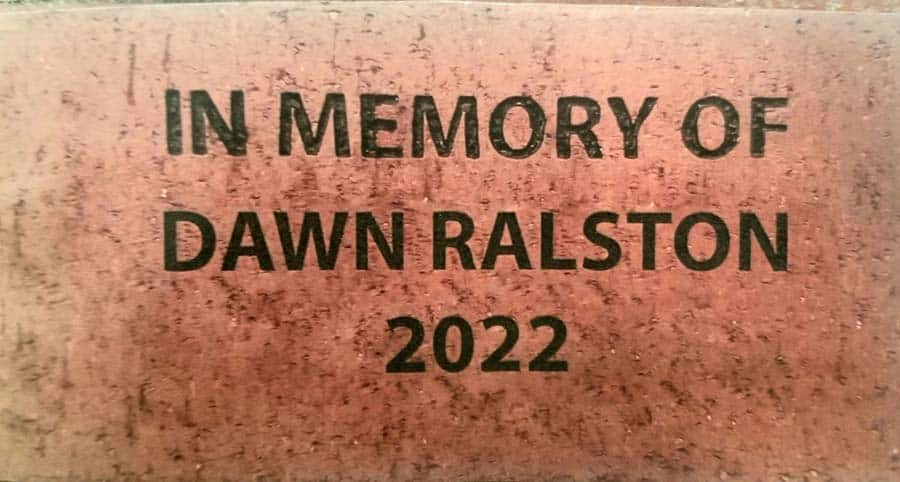

Some donors choose to earmark their gifts for specific items, and we certainly honor that. We thank the group that gave us the ice-crushing machine, and another that paid for dementia kits for nursing home patients. Others give in memory of a loved one, by buying a brick for our walkway or a leaf for our tree. A new addition is the Hospice Hero wall, where people honor a staff member whose care made a particular difference in their lives. Most just give to a general fund, and that money adds up to 15% of the cost of the entire Connecticut Hospice budget.

We should not forget that many give of their time and talents. The dedicated pet owners who bring their dogs to visit lonely patients, or the musicians that play in the lobby or in the wings of the inpatient facility, or the barber who came to cut hair—all of them are indispensable. Medicare actually requires that 5% of all of our work be done by volunteers, and we have hundreds of them, from high school and college students to retired professionals of all kinds, most of whom say that they get more out of volunteering than they put in. Our reports to the government have to show a monetary value to all of that time, and it really adds up.

Businesses also participate, bringing groups of volunteers for service days, or donating materials and food. We receive donations of flowers, and have volunteers who help to keep our plants thriving. Many companies cut their rates for nonprofits, or at least for us. Even our fundraisers and other events depend upon donations and volunteer workers.

The saying that “it takes a village” is never more true than at Connecticut Hospice. We are grateful every day for the kindness of friends and strangers. Our patients and their families are thankful as well, and no donation of any kind is too small to make a difference in the lives of those in need.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

As a not-for-profit, we depend in part upon generous donors who understand that unlike our for-profit competitors, we provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare or private insurance. We strive to go above and beyond the standards set for hospice care, and your generosity allows us to do so.

Hospice programs are required to provide social work services as a “Condition of Participation” for the Medicare Hospice benefit, but many families do not realize the extensive components offered.

In fact, it can sometimes be difficult for social workers to get into homes to see families, where home hospice care is being given. Although there can be feelings of wanting to withdraw from outside interventions or visits, more often it is because people do not fully grasp the wide breadth of what hospice social work offers.

The first standard of hospice social work is to do what is called an initial assessment. It provides an early glimpse of where the patient and his or her loved ones are, in terms of their understanding of the illness and its progression, preparation for decisions that may need to be made, and where they are in the grief process.

It is not uncommon for families to express their feelings that they have no need for any such help, and to see taking any advice or counsel as somehow being a sign of dysfunction, or an inability to care for their loved one properly.

Social workers go far beyond what that would imply, about being there to fill in where a family cannot cope. Although that can be true, a more useful way to think about their services is to compare them to a compassionate and expert event planner. Death has its own set of rituals, red tape, financial considerations, and especially emotional ramifications. Sitting with someone who does this for a living can not only bring comfort and clarity, but can ease many practical burdens that arise with sometimes overwhelming speed, as health declines.

One important early conversation, with the patient if he/she is able, or otherwise with the family or friends, is about the goals of care.

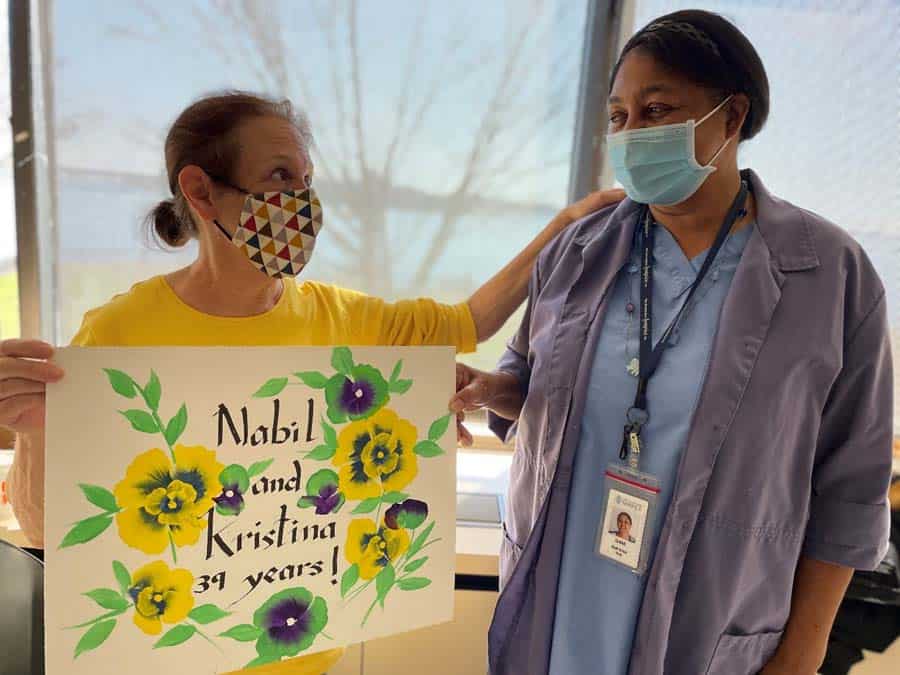

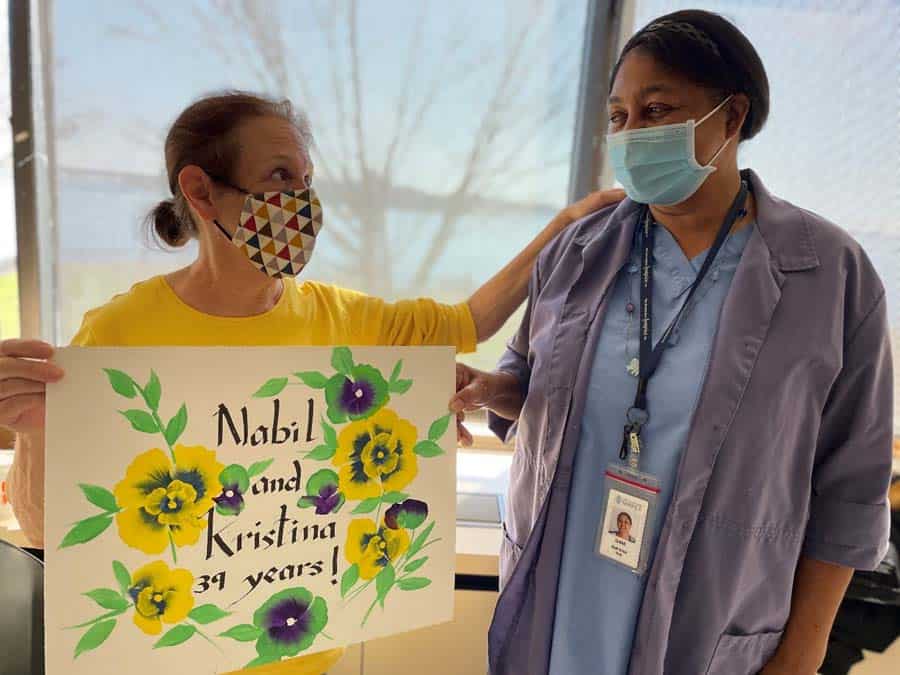

That last question leads to what is perhaps the most joyous part of a social worker’s job. Maybe there is an upcoming marriage that can be accelerated. Social workers have planned weddings, both for patients and for their children and grandchildren, sometimes even in our inpatient facility or on its waterfront grounds. One family wanted a Disney-themed wedding, to commemorate a family trip, and the social work staff decorated the room, while the arts staff brushed up on Disney tunes to play at the bedside. A beaming bride had mouse ears on, to complement her wedding dress.

Other ceremonies have taken place with regularity, such as birthday parties or anniversary celebrations.

One of the most poignant was a graduation, where the professors came in academic garb, to present the patient with her recently earned diploma. In all of these cases, the social work staff works with the family to achieve those goals.

Goodbyes of all kinds also fall into hospice social workers' purview. Dealing with children’s grief, and the preferences of the patient and other relatives can be a difficult, but rewarding task. There may be times when patients need transportation by ambulance, in order to say those farewells to a person or place, and social workers can make that happen. When the hospice care is not in the home, there can be arrangements made for pets to be present. Even a horse came to our backyard, so that its owner could see it one last time.

Last wishes can range from a favorite food to a video to leave behind, from putting toes in the ocean at the end of life to finishing a last book or article. Whatever closure means becomes the social worker’s goal to facilitate.

Planning a memorial service or funeral falls into the category of last wishes, as well as deciding about DNR/DNI or treatment choices. Even broaching those subjects with family members can be something in which the social worker participates, especially when some relatives have not understood or accepted the disease trajectory.

Financial considerations, including Title XIX applications, can be explained by social workers. They also do discharge planning when people can no longer live independently, and can help to narrow the options and help with the choice of a nursing home, should that be necessary. They are charged with making sure that the patient is safe in whatever environment is chosen.

When there are no relatives, a social worker can even take over some of the role that a family member would otherwise play. They can reach out to people that the patient wants to see, help with household tasks, or just keep someone company. One often-made comment about the end of life is that the days may be short, but the minutes and hours can be long. Having someone objective with whom to talk can be so important.

By now it is clear that social workers fill a vital role in many aspects of hospice care, no matter the setting of that care. They are special people, and they bring a combination of practicality and compassion that is so necessary for both patients and families. Whether they are serving as coordinators or counselors, they can play a part in every patient’s journey. Developing a relationship with them early in the process can make a difference all along the way. If there is a question of any kind, and the social worker doesn’t know the answer, he or she probably knows how to help get that answer.

Most of us know social workers in some setting, because they are so versatile in their career choices. What they do varies tremendously by location, so a school social worker or a prison social worker may do very diverse jobs. It is hard to imagine, however, that anyone could have a position that is more fluid that that of a hospice social worker. They are truly indispensable.

Of all the questions we get asked by families calling our Admissions Office at The Connecticut Hospice, this is the most common one, and one of the hardest to answer. The very short answer is that Medicare is calling the shots for hospice providers.

There are many rules that govern hospice care and hospice eligibility. Some people, who are not primarily covered by Medicaid or Medicare, have insurance plans with gatekeepers, who dictate whether someone can have their stay in our inpatient unit covered by their insurance plan, and for how long. This is mostly for those under 65, and, while companies and plans vary, such admissions are generally approved. At least one large employer in our region has a lifetime limit on hospice care of all kinds, but that type of restriction is rare.

Almost 95% of our patients on our home care or inpatient service are covered by either Medicare or Medicare. Those rules are set by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which is part of the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Federal department that governs, among other things, Medicare reimbursement. Connecticut Hospice was the first provider in the country to be reimbursed by Medicare for hospice care, and that bill was passed in 1983. It is updated annually as to rates, and there are sometimes changes in the rules, or new interpretations of those rules.

Recently, these interpretations have focused on fraud, with half of the CARES Act money during COVID going toward more investigators, to make sure that people are not being covered for hospice care if they are not entitled to it. While the standard is not black and white, the most commonly cited dictum is that the patient’s primary diagnosis, if left untreated, would likely result in death within six months. This is invoked so often that it is shocking to note that the period of time—six months—was chosen arbitrarily at the time the original bill was enacted. While there has been much encouragement from the industry to make that period 12 or even 24 months, that has not yet happened.

Once the patient’s eligibility for hospice care has been established, there is a further requirement for inpatient care to be allowed. The rule is that the patient cannot be feasibly treated in another setting. Clearly, that is a definition that cannot be applied without using some medical judgment. Symptom management must be required at a level which cannot be sustained in the home or in a skilled nursing facility. Generally, this would refer to breakthrough pain, extreme agitation, or the need for frequent adjustments in medication with an onsite pharmacy.

The most shocking part of the above definition is that nowhere does it refer to the patient’s prognosis. Dying is not, by itself, a criterion for inpatient hospice care. “Comfrtable” is not a condition that, while all hospices strive to achieve it, is acceptable in an inpatient setting, except with respite care.

Respite care is allowed by Medicare for no more than five days during each certification period (60 or 90 days). Patients can come to an inpatient facility for pain management or caregiver breakdown (again, not a term that has an unambiguous definition).

Sometimes, non-hospice patients can also be brought to an inpatient unit for symptom management, on a Diagnostic Related Group (DRG) basis. That can only happen at Connecticut Hospice because we are separately licensed as an acute care specialty hospital, in addition to being licensed as an inpatient hospice and as a home hospice. That would be a limited stay to address issues or adjust medications, with the idea that the patient could then return home. Since those patients are not enrolled in hospice, they don’t need to qualify in any particular way for CMS, but they do need to require symptom management.

It is certainly understandable that patients and their families would find all these rules confusing, and perhaps unfair. Each family has its own understanding of what care at home entails, and differing capacities for providing it. What constitutes an acceptable level of home care by the family, according to Medicare, can include up to 18 injections per day of medication. Even when a caregiver can provide that level of support, the strain of not sleeping, especially if the patient is agitated and restless, can be extremely wearing. When they call about an inpatient bed, and are told that their loved one is not inpatient eligible, that can be very upsetting to hear.

Unfortunately, we have the beds to take those patients, but not the ability to get paid the inpatient rate for them. Occasionally, and more often during COVID, families whose loved one qualifies for home (routine) hospice care may choose to bring them into our inpatient facility, and privately pay the difference between what Medicare will pay for home care, and what it pays for inpatient care.

We are incredibly sympathetic to those who find this onerous, and totally understand that it is not a choice that every family can afford to make. The entire industry is lobbying for a better, fairer, and more comprehensive approach to end-of-life care in this country. As the baby boomers age, our collective system for caring for those with terminal illnesses will be stressed to the breaking point. Some cultures deal with this issue differently, but, in our increasingly global culture, not everyone will live close enough to their elders for family care to work.

It sounds like a bad joke to tell people to “write to their Congressional representatives”, but that is the only way things will change. In the meantime, Medicare and Medicaid will continue to dictate the amount of care it will provide, and the amount they will pay providers to give it. When they audit hospice providers, which they are doing on an alarmingly increasing basis, they can unilaterally decide that someone didn’t need to be in inpatient hospice care, or in hospice care at all. At that point, they withdraw the money for that patient from our account with them, and we can either accept that, or go to an Administrative Law Judge to appeal the ruling. That process takes up to five years, during which we do not have the use of the money, even if we win it back in the end. Some hospices have simply shut their doors in these circumstances, since they are spending their time in litigation rather than in patient care.

All of this is a very long answer to the simple question of why we say no to so many patient families who inquire about inpatient care. While we would love to provide it, we cannot do so, if it means that we will be doing it for free. Therefore, we have to apply the same lens that the government uses when evaluating a patient, and that causes us to turn down many people we would otherwise admit.

So, if you are calling us about an admission, you and your doctor must be prepared to meet the standard that our inpatient facility is the only feasible place to treat the patient’s pain and symptoms. All of us know that we are experts in providing the best in end-of-life care, but we are not the ones deciding when we are allowed to do that. If privately paying the difference is an option for your family, we are happy to discuss that avenue, but we are not trying to push people toward that alternative. In a perfect world, we would take all comers, and care for them with our customary competence and compassion. Until such a system exists, we will care for all those whom we are approved to take on an inpatient basis, and offer home hospice care to the others, if they qualify for that service.

We hope you understand that we are sympathetic to your needs, and are doing our best to accommodate all the patients we can.

The Connecticut Hospice, established in 1974 as the first Hospice in America, has always been dedicated to honoring all patients and families affected by life-limiting illnesses with integrity, support, and compassion. This dedication includes an increased commitment to the special needs of veteran patients and is supported by a new partnership with the We Honor Veterans program.

We Honor Veterans is a collaborative effort by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), which invites hospices and VA facilities to join a program focused on serving the unique needs of America’s Veterans and their families. Participating organizations bolster their service to Veterans by moving through five levels of partnership.

At Connecticut Hospice, the We Honor Veterans program is viewed as a great opportunity to formalize and advance the organization’s commitment to veteran patients. As We Honor Veterans has become more integrated into the organization’s services offered, the positive impact on veteran patients and their families has become evident from the smiles on the patients’ faces.

The most recent veteran-focused event was held this past Memorial Day, May 30, 2022, when Connecticut Hospice welcomed Branford, Connecticut’s Scouting Troop # 688, representing the Boy Scouts of America, to present the colors at a special honor guard ceremony.

Some Connecticut Hospice patients, families, and staff assembled on the waterfront side of the campus to partake in the event, while others watched from their room windows. The scouts, ranging in age and rank, were accompanied by troop leaders, Michael Loffredo, Brian Appleby, Deidre Salemme, and Crystal Bailey-Loffredo.

The Memorial Day program opened with a prayer and a brief history of Memorial Day. Scout Master Loffredo then read the legendary Gettysburg Address, which President Lincoln delivered on November 19, 1863. Scout Master Loffredo also gave a detailed account of wars with American involvement, including years fought and the number of United States servicemen and women who have lost their lives – currently this is quoted at over 1 million. The afternoon concluded with the playing of Taps by a member of the troop, a recitation of the call’s lyrics, and finally with the retiring of the colors.

Both the scouts and troop leaders took the opportunity to interact with several of Connecticut Hospice veteran patients, who proudly attended the special Memorial Day presentation, and thoroughly enjoyed sharing his military stories to an eager audience.

Prior to the day’s events, our Veteran Volunteer, Joe Marino, who served in the army as a dentist in both Desert Storm and Gulf War, presented personalized recognition certificates to all Veterans currently receiving care in our inpatient hospice unit.

Connecticut Hospice has also implemented a process of placing a small flag on the bottom of a veteran patient’s bed upon passing. It is just another way to pay respect to veterans for their service.

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.