Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

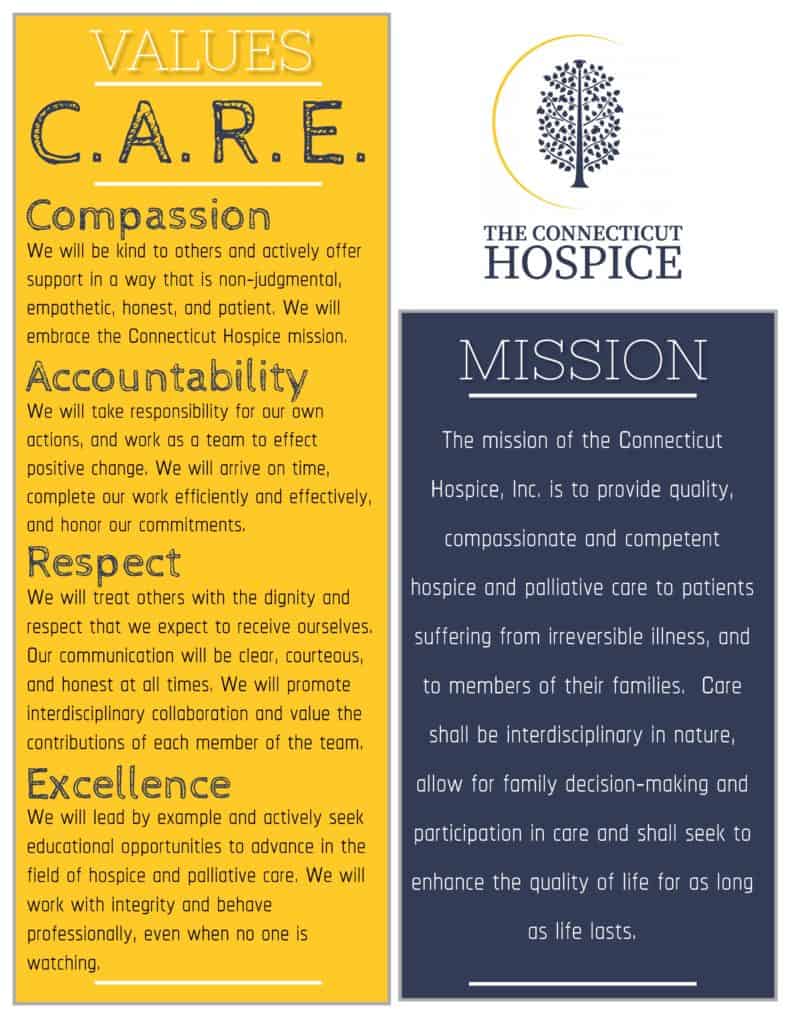

What makes Connecticut Hospice the right choice for hospice and palliative care? A staff that is guided by core values of C.A.R.E. to ensure the best in patient and family care. While a lot has changed since the start of Hospice in 1974, the quality of care provided has remained the same. In a recent new hire orientation, CEO, Barbara Pearce, stressed the importance of sharing not only the history and mission of The Connecticut Hospice to all new employees, but it is equally important to instill the guiding principles that all staff must follow to continue delivering the utmost quality of care: Compassion, Accountability, Respect, and Excellence (C.A.R.E.).

Beyond a shadow of doubt, the work that is done by each member of the Connecticut Hospice team matters and is valued by the organization as well as those impacted. Though quite frequently, when speaking with a Connecticut Hospice employee or volunteer, they will tell you that the work they do makes just as big an impact on their lives as those they care for.

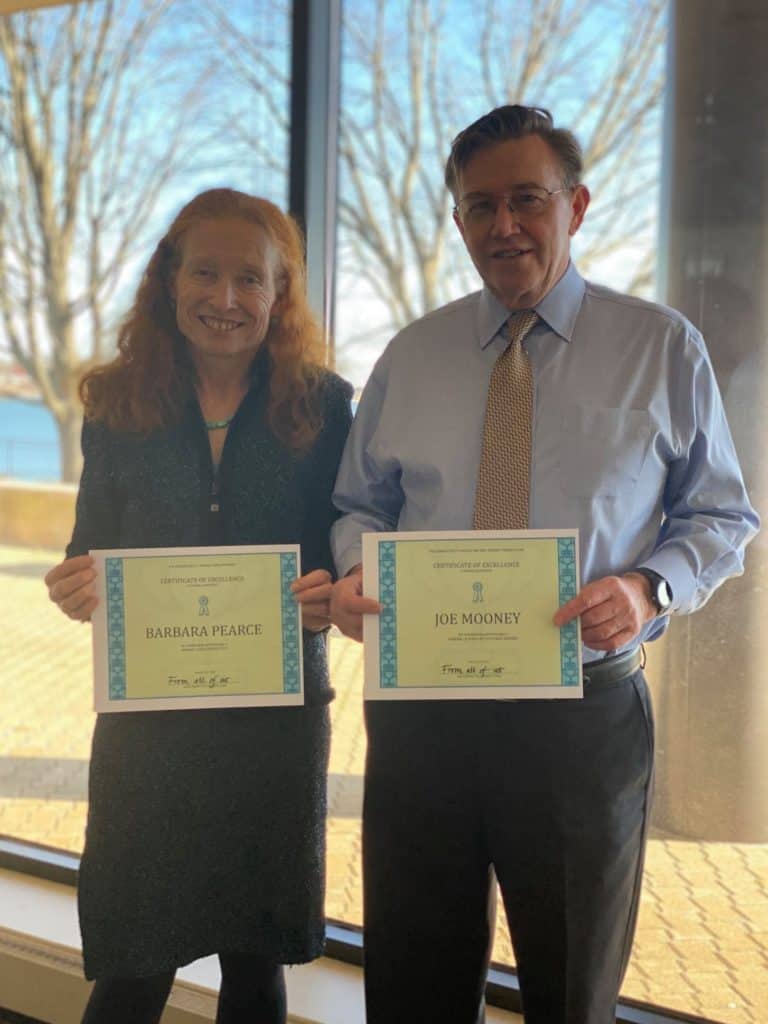

February 1, 2021 marked the 2nd anniversary of new leadership taking over The Connecticut Hospice. It was a relief for the staff when Barbara Pearce, CEO, and Joseph Mooney, CFO, arrived bringing hope for American's 1st Hospice. And, while it is no secret of the mountain of challenges and changes the non-profit has been through over the last two years, it isn't until you hear them spoken out loud that it becomes apparent that Connecticut Hospice is resilient.

In a recent interview, Barbara Pearce, CEO, shared her recollection of her last two years at Connecticut Hospice, with Bruce Tulgan, creator of The Indispensables podcast. Listening to Barbara share the numerous and sometimes grueling challenges the organization has faced during the last two years, it becomes clear why Connecticut Hospice has been around for forty-seven years -- hospice care started at and continues at Connecticut Hospice.

Use link below to hear the full podcast.

The Indispensables Podcast

Conversations with real go-to people who stand the test of time in the real world of work. Based on Bruce Tulgan's new book, The Art of Being Indispensable at Work, The Indispensables is a podcast series about how real people, in the real world, become indispensable, go-to people who stand the test of time at work. For more information, visit Rainmaker Thinking.

"Connecticut Hospice may not be able to add days to your life, but it can certainly add life to your days." -Barbara Pearce

If you have ever wondered, "What happens at hospice?" or, "What to expect for hospice care?" This post will walk you through a day in the life of a hospice.

People have preconceived notions about what hospice life must be like, and it usually involves words like “depressing”, “sad”, or “painful”. Connecticut Hospice, the country’s first hospice and a pioneer in end of life care for almost fifty years, is none of those things.

If one were to walk onto the inpatient floor, very early in the morning, the first impression is one of peace and quiet. There are no beeping machines, overhead lights, or loudly speaking caregivers, that characterize so many other health care institutions. Here, they are still hours from breakfast, with family members who have slept on a cot at the bedside of a loved one roaming the halls, looking for fresh coffee on each end of the floor. Nurses and doctors are whispering morning greetings, and huddling about the patients and their conditions overnight. Everyone who is awake is soon watching another beautiful sunrise over Long Island Sound. No matter the weather, or the season, it’s always a joy to see the sun come up over the water at our 52-bed, waterfront inpatient facility.

On the other floors, home healthcare nurses and aides are picking up supplies, checking in with supervisors, and communing over whatever snacks have been left out by grateful families. Maintenance and kitchen workers are going about their days, while office workers are settling in for the morning. The pharmacy is buzzing with activity, as they calibrate dosages and adjust drugs after the night reports are in. Early birds have begun to churn out their work, while other offices await occupants.

Not everyone wears scrubs, but many do, especially if they interact with patients. Nurses and Certified Nurse Assistants each have special colors, except on Friday, when any color goes. The holidays bring a relaxation of the color rules, and a lot more red and green apparel is seen, along with reindeer headbands. In other departments, people can wear any color, though the current favorite is probably black, which is far more chic than the baggy blue handed out to staff. One such fashion plate has even had his monogrammed!

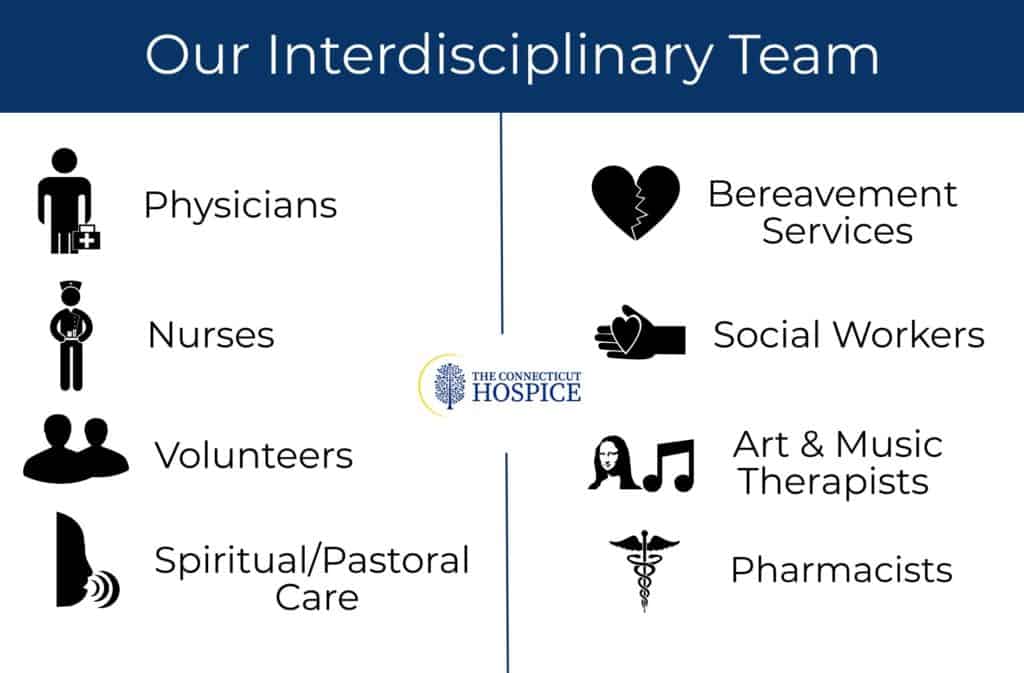

9 AM is midmorning for some, but many other people are still arriving. The official start of many homecare days is the IDT meeting. That stands for Interdisciplinary Team, which is what Medicare requires for care coordination. Our comprehensive approach to hospice and palliative care is delivered by a medically directed, nurse-coordinated, interdisciplinary team, which consists of hospice and palliative board-certified physicians, nurses and pharmacists.

Despite its being required, many professionals have come to love the IDT meetings. Much of their time is spent on the road and working alone with patients and families, so they value the camaraderie and mutual support of the IDT. Teaching also takes place, with doctors and supervisors sharing medical knowledge or regulatory updates. The meeting can last for two or two and a half hours, after which everyone rushes off to begin daily home and nursing home visits. Once a week, the inpatient care team holds the same IDT meeting, where colleagues who do work together every day pause to consider treatment options and suggestions.

By midmorning, visitors have begun to arrive. The front desk is staffed all day and evening, often by volunteers. They kindly greet each arriving party, explain the CT Hospice rules (especially during COVID), and comfort those waiting for a turn to go upstairs. Sometimes the lilting music of a grand piano drifts down the entrance hallway, where a volunteer plays for those who gather. It is not unusual to see a wheelchair or a bed rolled in for an impromptu or planned concert.

Those who work in support capacities are in full swing, paying bills, raising charitable funds to supplement Medicare reimbursements, hiring new staff members and volunteers, keeping track of all the rules and regulations that govern a hospice’s existence.

On nice days, families often take their loved ones outside. All the beds can be moved, and there is often a staff member or volunteer to help a patient who wants to be in the sunshine, but doesn’t have someone visiting. Small groups can be seen outside around the beds, at picnic tables scattered over the rolling lawn, or in the gazebo down by the double beach that gives the street its name. At high tide, that beach disappears, but, at low tide, family members can be spotted climbing on the rocks and enjoying the view. Raised flower beds grace the exit doors, reminding everyone of the circle of life.

Lunchtime for patients happens as one would imagine, with trays delivered to beds. It’s not uncommon, however, to see a peach, some potato chips, or another treat sent up from the kitchen for a patient with a sudden craving. Some visitors bring favorite foods or drinks, while others (including staff), use delivery services from nearby restaurants. The staff eats on a separate floor, where the table is often piled with goodies brought by family members, or donated by outside groups. Halloween and Christmas both involve lots of extra calories!

All afternoon, there is a steady stream of ambulances delivering patients, or transporting respite patients back home. Each new arrival is greeted efficiently and compassionately. Those who enter in pain are usually made comfortable right away. By then, the evening shift has taken over, and new nurses and CNAs are checking on patient comfort levels, calling family members with updates, or attending to documentation on rolling computer trays.

Music and art therapists are going bed to bed, helping patients with requests or just easing loneliness. They have made videos for loved ones, collages, sketches, or other mementos. They help make Facetime calls to relatives, on iPads there for that purpose and play music that releases and relives old memories. Volunteers are also in full swing, either sitting quietly with those resting or wanting silence, chatting with others wishing for company, or playing music in the hallways. Some bring pets trained for visitation in hospitals, and they are particular favorites of everyone! Pastoral care professionals and volunteers visit each bedside, arrange for outside clergy when requested, pray with families, offer use of the prayer room tucked away down a side hall, or hold services in the common room.

As the sun sets, people pause to mark its beauty over the horizon, and begin winding down. Visitors still come, at all hours of the day and night, and the building is open around the clock. Cots are brought for those who plan to stay overnight. Clerical and support staffs head home, and the activity level goes down. People are still admitted during the off hours, but most are there, ready to be tucked in for the night.

And what of the patients in the beds? How does all of this activity affect them, in their final days? As many people have noted, at the end of life the days left are short, but the hours can be long. Decreased mobility, motivation, or purpose can diminish quality of life during a terminal illness. Volunteers, therapists, social workers, clergy, and medical staff all strive to help patients achieve closure, whatever that means for them, find peace, and eliminate pain and fear. To an astonishing extent, they succeed in that mission most of the time. Patients live fully until the end of their time, and find meaning and enjoyment wherever possible. As one patient famously said, “I came here to die, and I learned how to live.” They are the center of the hospice community, and they bask in that attention and concern.

Elsewhere in the facility, workers are still cleaning, cooking, fixing things, writing reports, and getting ready for the next day. Someone is always around, answering the phone for anxious family questions, dealing with crises in home care or in other settings, or completing yet another written report. Sometime during the night, someone changes the mat in the elevator to display the next day’s name (today is Wednesday), and another day begins, softly and lovingly.

In the interview, Barbara discusses what differentiates Connecticut Hospice from other end-of-life care programs in Connecticut, including our rich history as America's first Hospice. Barbara also references our founder, Florence Wald, former dean of the Yale School of Nursing.

Barbara speaks about how Connecticut Hospice is making significant efforts to continue allowing visitors during COVID. As a holistic program that values patient and family-centered care, Connecticut Hospice understands how important it is for patients to see their loved ones during end-of-life care, most especially during the holidays.

The article also features footage of the glorious water views of Long Island Sound and the beautiful grounds for visitors to gather in larger (up to five people) socially distant groups.

For the month of December, Connecticut Hospice is lighting up the grounds with many trees strung with holiday lights in memory of loved ones. Supporters can sponsor fully lit trees or individual strings of lights or menorah bulbs.

There are also fully decorated trees on display in the lobby that have been donated by organizations and individuals. The decorated trees are offered in a silent auction, which is running through December 13th, 2020.

Barbara offers a special thanks to the Branford Rotary Club who has helped tremendously with the Lights of Love virtual fundraiser, including putting up all of the holiday trees.

"Connecticut Hospice may not be able to add days to your life, but it can certainly add life to your days." -Barbara Pearce

Fashion often seizes on wearables that have been introduced for functional reasons. Take leggings, for example. First a sports-only item designed for unencumbered movement on a bike or in a gym, now people wear them for style and own several pairs. Jeans? These sturdy pants designed for laborers are now stacked in so many closets in multiple washes, lengths and cuts. Glasses too – I remember my first pair was pretty basic. Now one finds glasses frames to fit their face shape and their personal style. If you browse online for frames you can try them on virtually; it’s amazing.

This past March, I wore my first face mask. It felt strange. I decided early on that voluntarily wearing a mask would feel awkward and make me stand out in my neighborhood. I also believed that wearing one was going to protect me and other people. If other people were going to wear them (to protect me and themselves) it seemed important that we normalize mask-wearing, the sooner the better.

I was walking down the street last spring and came upon some of my friends standing and talking. Everyone stood at a distance but I was the only one wearing a mask. One friend is a surgeon who worked at a hospital where cases were rising and protocols were evolving. With his daughter at his side, he called out to me, “That mask isn’t going to do anything for you, and they can even cause harm. If everyone starts wearing masks, they’ll increase demand for N-95 masks that are needed in the hospitals. The mask you are wearing does nothing.” He gently mocked me for wearing it. I said that I’d heard that argument but also some different well-informed opinions on the efficacy of mask-wearing. He replied that I had a false sense of security with the mask and that others would too. Slowly but surely over the spring into the summer, masks became more common than not; it’s unusual to see someone without one (even my surgeon friend).

The truth is, an N-95 mask is the most effective due to the random pattern of its fibers and its electromagnetic charge to attract and trap aerosol particles. A mask made of tightly woven cotton or an ordinary surgical mask does an excellent job too, especially if two people who may be near each other are wearing them. The small amount of particles that escape one person’s mask, if they even manage to reach the other person, are filtered yet again by their mask – vastly decreasing the transmission of coronavirus particles.

Possibly the most important factor in mask-wearing is the way the mask fits. It should be ample in size, snug against the face, and in a shape that allows breathing space inside the mask. A loose mask leaks particles. This is why wearing a bandana that is open below the chin offers very little protection.

Always wear your mask over your nose, make sure your chin is covered, and keep your mask snug. Discard disposable masks, and frequently wash the cotton ones. If you need to go indoors, you can even slip a coffee filter in your mask for another layer of protection.

It may be that one day soon, we will not strictly need to wear masks, or will use them for certain situations, like at movie theaters or basketball games. One thing for sure is that right now, masks are essential. And if wearing them everywhere is not mandated by law, most institutions, including banks, hair salons and certainly healthcare settings, require them, for good reason.

Wearing a mask feels inconvenient, but seatbelts probably felt that way in 1966, right? Did you know that in the 1940s and 50s, even as scientific research demonstrated that they saved lives, many people asserted the opposite, and even cut them out of their cars? So many lives were lost before seat belts became mandatory. Let’s not make the same mistake with masks.

Small confession: I may go from reluctant user to enthusiastic wearer of masks this winter. They do a nice job of keeping my face warm. And back to fashion, lots of people have several masks, and they even think about matching the sweater they are wearing, or matching the weather. Some have straps, some ear loops, some velcro, are printed with creative patterns and colors and even political statements . . . are masks becoming a style item? After all, we wear them on our very faces! I myself have some fall colors in mind for the next ones I make. And apparently, designers and shops like Lily Pulitzer, Uniqlo, Levis, Etsy, even Louis Vuitton and Gucci – are standing by to help!!!

Sources:

Wisconsin Public Radio, The Surprisingly Controversial History Of Seat Belts September 25, 2017 read the article

New York Times, How NOT to wear a mask, April 8, 2020 read the article

New York Times, Masks Work. Really. We’ll show you How, October 30, 2020 read the article

LeviStrauss.com The History of Denim, July 4, 2019 read the article

When one enters The Connecticut Hospice, it becomes almost immediately clear what a nurse-centric place it is. There’s a reason for that, and her name is Florence Wald. She was our founder, often called the Mother of Hospice in America.

For many years, the nurses have asked for a picture of our founder on the inpatient floor. Through the good graces of two retired Connecticut Hospice nurses, Gen O’Connell and Dianne Puzycki, and portrait painter, Angela Rose Agnello, (daughter of staff nurse), we unveiled the portrait of Florence Wald on the second floor yesterday, to great applause.

We have written elsewhere about our history, and the long list of our accomplishments, but it’s important also to understand just how Florence Wald changed the care of patients with terminal illnesses. After she spent time at the world’s first hospice in London, Saint Christopher’s, she returned with determination to alter the course of end of life care.

At that time, in the early 1970s, people often wouldn’t even say the word “cancer” out loud. Some of you remember when it was referred to as the “Big C”. There were even those who feared that cancer could be contagious, and were afraid to be too close to those who had it. Of course, in those days, the likelihood of survival was much lower. Sometimes, doctors didn’t tell patients, or families, what the course of the disease would be, or that person’s prognosis. This led to people dying without closure, or with survivors only beginning to process their grief.

For all these reasons, Ms. Wald decided early on to focus on the care of cancer patients. She was a force of nature, and was determined to change what many doctors and nurses considered standard practice at the time. Researchers can read many of Florence Wald’s papers, thanks to the Yale School of Nursing.

Of particular concerns was what happened to those left behind, especially children of cancer patients. This might not be considered a good idea by many, but she got involved in the lives of the families, even taking some of the children home with her. She wanted them to have the comfort they weren’t getting in the medical system of that time.

Medicare set up what are now known as COP, Conditions of Participation, and they govern what hospice care needs to include. One of those requirements, 13 months of bereavement care for the survivors, is now practiced everywhere, and most likely came from those early principles espoused by Florence Wald.

Much of what we consider essential for death with dignity also harks back to those first patients. We now have a Plan of Care for everyone, and patients participate to whatever extent they can in planning for their end of life care. Doctors are now taught in medical school to have those difficult conversations, although many of them say that much more training is necessary. And, even though there is still a tension between the medical profession’s drive to keep patients alive, and the realities of the likely outcomes, we do see people choosing palliative care, when curative treatment becomes risky or speculative.

Cancer is not a verboten word anymore, but our tradition of treating the dying, no matter the cause, continues. We took wonderful care of AIDS patients in the early days of that scourge, and today we accept COVID-positive patients into our care. We try to give patients peace, comfort, freedom from pain, and closure, in whatever form that takes for them.

Florence would have been proud of us when we arranged for a dying man to say goodbye to his horse on our lawn, or when a social worker put another man’s feet into buckets of water pulled up onto his bed, so that he could feel the seawater one last time. Or, when a patient got to experience one last surprise birthday celebration, and share it with her family living on the other side of the country.

We are grateful for the wonderful legacy we have from Florence Wald and those early nurses who toiled alongside her. The world is a better place because of her work, and what better closure could there be to a life?

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.