Please view our updated COVID-19 guidelines and visiting procedures →.

The Hospice Plan of Care (POC) maps out the needs and services supplied to hospice patients and their caregivers.

If one wanted to probe the essence of the hospice philosophy, it would probably come down to the hospice plan of care, developed for each patient on admission, and revisited every two weeks after that, by the interdisciplinary team managing that individual patient. This plan is mandated under Medicare for hospice reimbursement and has very specific requirements that all hospices must follow. It isn’t just that various disciplines are included in the plan, but that all the practitioners convene to contribute to it. The Connecticut Hospice is very familiar with all these components, since our Founder, Florence Wald, wrote extensively about the various aspects needed for proper patient treatment, as she worked to bring the first hospice care to America almost fifty years ago.

At the heart of what Florence Wald believed was the notion that patients have rights, and should be treated as partners in the care that they receive. She thought, and it was novel at that time, that they should be told their diagnoses and prognoses, and that the whole family should be involved in planning and care of the illness. It seems hard to imagine now, but cancer patients were often not told what their disease was, nor were they advised if it was terminal. This was seen as a kindness, but Ms. Wald felt that it impeded a patient’s ability to achieve closure, and to plan for his or her last days, weeks, or months of life. Today this appears obvious, but, at the time, it led to the idea that there should be an informed discussion about options, treatment, and a patient’s wishes.

This Hospice Plan of Care goes far beyond the concept of advanced directives that many people are familiar with from medical practice currently. It is a plan for comprehensive care that includes preferences about pain medication, sedition, home vs. hospital vs. hospice as a location of care, treatment choices, comfort measures desired, and family involvement. It also includes the more expected areas of funeral arrangements and religious practices, as well as financial considerations.

To many patients and families, the end of life can come as a surprise, no matter how often they may have spoken of the possibility. Too often, they can feel as though they have boarded a train that is proceeding quickly, and without their full informed consent in some instances, toward a destination, they may not feel that they have accepted. There can also be a sense that everything is preordained—that the medical profession will be deciding the next steps, based on superior knowledge. This usually leads to further treatment, either because paths forward presented as possibilities are not understood to be optional, curative, or even recommended, or because someone in the group is choosing extended life as the goal for action, no matter the chances or consequences. Without deliberative planning, this runaway train can end up in a place no one consciously intended to go.

How does a hospice plan of care prevent this runaway train of futile, expensive, and often painful curative attempts? First of all, the care plan is patient and family-centered. The aim is to make sure that the patient’s goals of care and treatment wishes are honored. Palliative care is very different from curative treatment, and both are explained. Comfort Measures Only (CMO) is a totally valid decision to make, and can, not infrequently, even lead to a longer life span. Treatment can be enervating, and frequent trips to the ER or lengthy hospital stays can weaken patients further, and lead to other issues.

Pain is another important topic. Not everyone has the same pain tolerance. Even if they did, some will choose to be more sedated than others, depending upon their own wishes for family visits, final projects, or other reasons. This is crucial to decide with the patient, if possible, since family members, or even the medical team, can be upset by signs of suffering, and want to have them alleviated.

Independence and residence are critical to discuss. For some, living at home is vitally important. Others may be afraid to be alone, or feel more comfortable with attendants around, either in the home, or in a skilled nursing facility. Some wish to undergo rehabilitation, to acquire the strength or ability to perform certain skills. Different options can also be right at different points.

When the end of life approaches, there can again be different preferences. Inpatient hospice care is often chosen by those who don’t wish to burden their relatives with personal care, or perhaps feel that their surviving family will be unhappy to have had them die at home. Some caretaker relatives may be increasingly unable to provide the level of support needed as the disease progresses. In other situations, the patient’s strongest wish may be to die at home. When this is true, all parties need to examine all the requirements necessary to achieve that result. For those who have spent a great deal of time in a particular hospital unit, they may wish to remain in a bed there.

Treating unrelated conditions is another consideration. Sometimes, antibiotics are used, even in CMO cases, to make the patient more comfortable. Others may wish to continue medications they have previously been taking. Many find letting go of all restrictions, dietary or otherwise, is a welcome relief. For them, the team dietician may be less important, but some families struggle to keep patient appetites up, and find that consultation valuable.

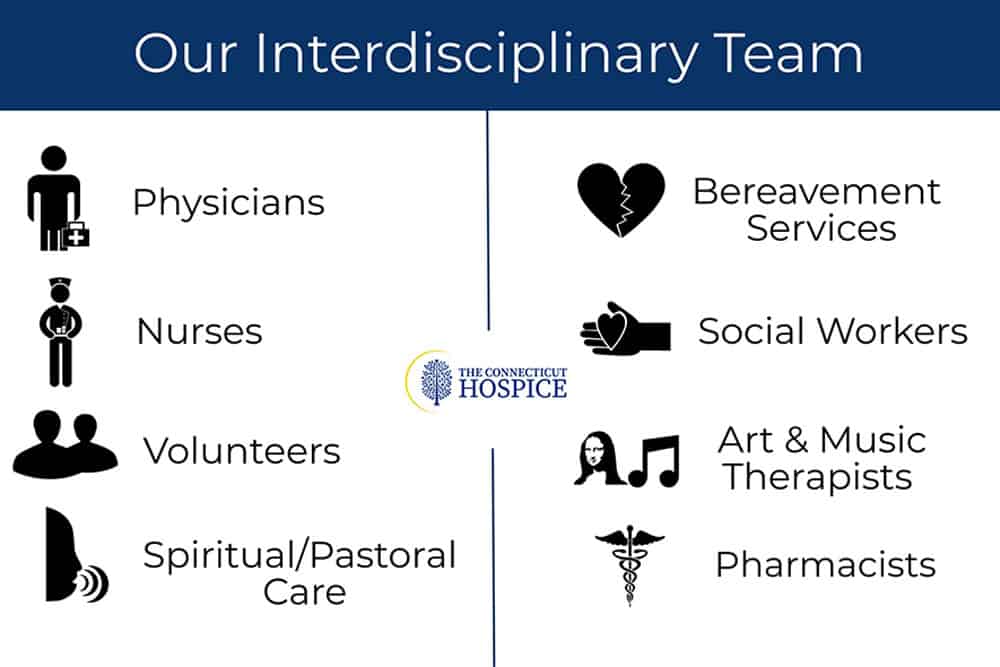

Social work, arts therapy, and spiritual care members of the Interdisciplinary Team are involved as well, not only for the typical end-of-life financial or funeral planning, but for help with bereavement and grief. The patient will rest more easily if resources are provided to work on those issues. The patient him- or herself may have spiritual questions or concerns. He or she may simply want to talk to a neutral listener, without fear of hurting feelings or causing pain. Working with an arts therapist, either in home care or in the inpatient unit, can be a way of creating new memories, or accessing old ones. Children especially tend to gravitate toward expressing their feelings through art and music. Assessments in these areas are done at the start of care, and reviewed, with action plans updated, on a regular basis.

How does all of this differ from what a patient and/or the family might accomplish alone? It isn’t always different. Some families are familiar with final illnesses, or extended personal care. Some have talked about what end-of-life wishes are, and all agree on one plan from the outset. If an illness has been lengthy, often especially in cases of dementia, decisions have already been made at various points. For others, however, this plan of care is a helpful introduction to all of the issues involved. For them, the caregiving team is very important in allowing them to accept, cope with, and come to terms with the process. Because there are many disciplines represented on the team, it can happen that different parts of the family relate to different styles or outlooks, and everyone can find relief in some regard.

Dr. Joseph Sacco, the Chief Medical Officer at The Connecticut Hospice, is certified in palliative care medicine, which he has been practicing for many years. He finds patient choice to be a true priority in good hospice care. As he explains, “What is left is choice — the right of patients and families to decide what their doctor should do, based on facts delivered clearly and with compassion.” That quote captures so well the philosophy of hospice: that it is the patient and family who are at the center of the constellation and driving the plan of care, and not the medical team. It is important for all parties to recognize that, even when it seems that there are no choices left, there are choices.

The decision as to how the end of life should unfold is a gift that all hospices can provide to their patients and families, and one that should never be taken for granted. It goes all the way back to the beginnings of hospice care, first in London, and then in Connecticut. The aim is to provide comfort and compassion, and allow all the dignity of fulfilling whatever wishes they can, to the best of their—and our—abilities.

As a not-for-profit, we depend on generous donors to help us provide customized services and therapies that aren’t completely covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance.

Please make a gift to help us sustain the highest standard of care.

Admissions may be scheduled seven days a week.

Call our Centralized Intake Department: (203) 315-7540.